Advertisement

The Last Bill JFK Signed — And The Mental Health Work Still Undone

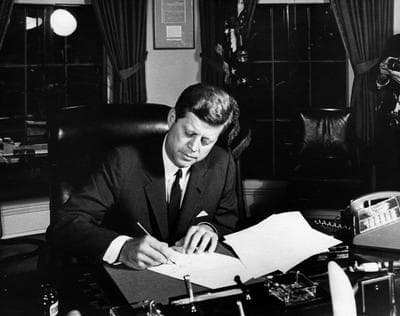

On Oct. 31, 1963, President John F. Kennedy signed a bill meant to free many thousands of Americans with mental illnesses from life in institutions. It envisioned building 1,500 outpatient mental health centers to offer them community-based care instead. The bill would be the last piece of legislation Kennedy would ever sign; he was assassinated three weeks later.

To mark the law's 50th anniversary, former Congressman Patrick Kennedy and others are convening at the Kennedy Library today to discuss how to improve mental health care now. Here, Vic DiGravio, president of the Association for Behavioral Healthcare, which represents Massachusetts community mental health clinics, comments on the law's effects — and what remains to be done.

By Vic DiGravio

Guest contributor

Fifty years ago, when President John F. Kennedy signed the Community Mental Health Act into law, the quality of life for hundreds of thousands of men, women and children in Massachusetts and across America was stunted and grim. For the most part, daily life was a gray tableau behind locked institutional doors, marked by inadequate treatment, primitive medications and isolation from family, friends and the community.

Patients in locked facilities were subject to retaliation if they complained about conditions. Family members were frequently discouraged from inquiring about care. Massachusetts and other states operated a patchwork of in-patient state hospitals that served as little more than systemic quarantine facilities.

In the final bill he signed into law before his death, President Kennedy called for society to embrace a new vision for people with mental health disorders and developmental disabilities, one in which the “cold mercy of custodial care would be replaced by the open warmth of community.”

Since then, perhaps no other field of health has changed as much and affected as many people as positively as the treatment of people with mental illness. The shift from in-patient to community-based care has created a more humane, effective and dignified network of support and treatment for men, women and children.

The three largest mental health providers in the nation today are jails.

In Massachusetts, we created a network of private community-based agencies to serve people where they work and live. Many of these organizations are members of the Association for Behavioral Healthcare. These organizations serve over 750,000 men, women and children each year.

On Wednesday, October 23, hundreds of behavioral health-care advocates, providers, researchers and policy makers will gather at the Kennedy Library in Boston, led by JFK’s nephew and former Rhode Island Congressman Patrick Kennedy, to commemorate the signing and discuss the need for a renewed commitment to support the millions of Americans and their families affected by mental illness, intellectual disabilities and addiction disorders.

The Community Mental Health Act reflected a bold new vision for the treatment of mental illness, but much remains to be done to fulfill that promise.

WHile the legislation did usher in positive and hopeful changes for millions of people with serious illnesses such as schizophrenia, progress stalled because of funding challenges and continuing stigma.

Only half of the proposed community mental health centers were ever built, and those were never fully funded. Drastic cuts were made to the remaining community mental health centers at the beginning of the Reagan administration.

The lack of access to community-based care leaves nowhere for the sickest people to turn, so they end up in hospital emergency rooms, homeless shelters or prison. "The three largest mental health providers in the nation today are jails: Cook County in Illinois, Los Angeles County and Rikers Island in New York," the Deseret News reports.

At the state and federal levels, further action is needed to fulfill President Kennedy’s vision of accessible, quality community-based care.

Today, in Congress, the pending Excellence in Mental Health Act would allow up to 1.5 million more Americans living with addiction and mental health needs, including 200,000 returning veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan, get the care they require. This bill has broad bipartisan support, but has been held up by the budget stalemate.

It would enable providers to become federally qualified certified behavioral health centers that are set up to screen, diagnose and treat people with serious mental illness and addiction with a full array of services. Funding and reimbursement rates would more accurately reflect the cost of providing care at these centers. The bill would bring important national standards to community-based behavioral health services.

In the wake of the Newtown shooting last year, a bipartisan group of lawmakers rallied to support the bill but it

has been held up by the budget stalemate.

Now that the debt ceiling and budget debates have been resolved for the time being, a group of senators led by Michigan Democrat Debbie Stabenow and Missouri Republican Roy Blount have revived efforts to pass the bill.

In Massachusetts, the Patrick Administration and legislature are beginning to wrestle with an ongoing crisis in access to outpatient services. Access to outpatient services is diminishing because inadequate reimbursement rates make it increasingly difficult for providers to operate. Last year, 84 percent of Association of Behavioral Healthcare members reported losing money providing out-patient care.

Just last week, the legislature adopted budget language to begin to address years of neglect to the outpatient system. We are hopeful the Patrick administration will follow the legislature's lead and approve this important bill.

JFK’s vision fifty years ago replaced despair with hope, and opened the door for community-based treatment. In Massachusetts and across the country, we have seen countless people with mental illness and addiction disorders recover and live full, productive and happy lives. We owe it to them to strengthen our resolve and go beyond promising quality mental health care. We must actually pay for it.

Vic DiGravio is president and CEO of the Association for Behavioral Healthcare.

This program aired on October 23, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.