Advertisement

Memories Of A Veteran's Son: Living With Undiagnosed PTSD

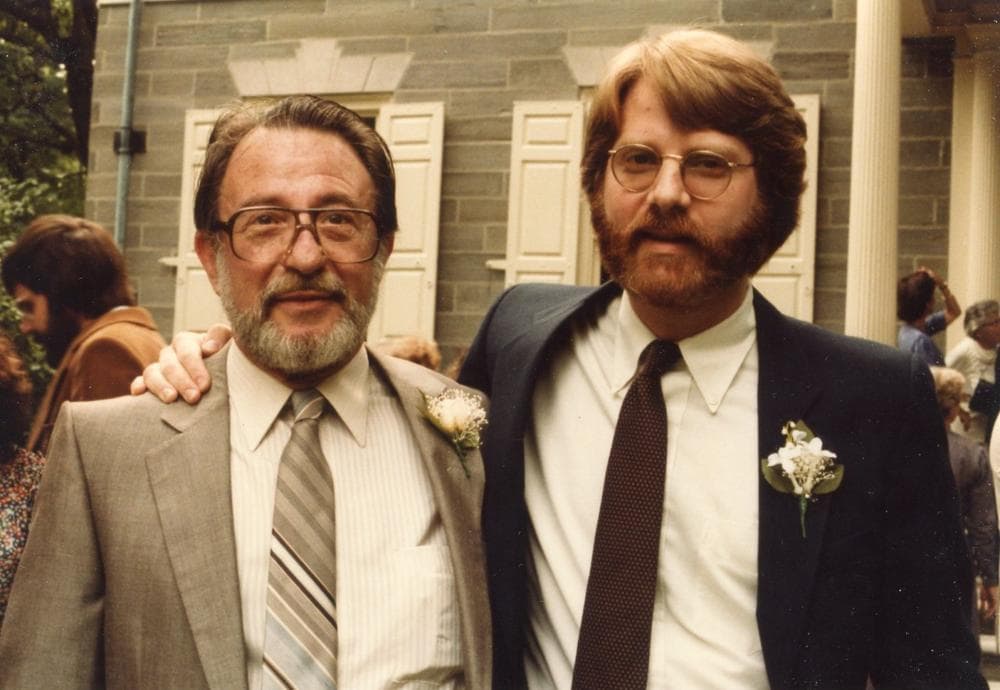

By Dr. Gene Beresin

Guest Contributor

Waking my dad early in the morning was terrifying. I learned not to do it – not an easy thing for a very young kid.

When I crept into my parents’ bedroom across the hall, I found that if I jumped into bed from my mom’s side, it all went just fine. But if I even tapped my dad and woke him from a sound sleep, he jumped a mile high, looking absolutely terrified, screaming, “What is it! What’s happening? What’s going on?”

It was damn scary. I learned quickly to go to the right side of the antique maple bed, never to the left.

And if I woke Dad from a nap in his study (he would often crash on the tiny bed there, working endlessly on lectures, slides and writing his books) he would jump and scream just as loudly. I stayed away and let my mom do it.

There were also the bouts for a week or two of shaking, sweating, and turning beet red, up night after night – events I recall once or twice during my childhood. Mom said not to worry; he was just having some kind of reaction to an illness he got in the war. “Malaria,” she said. “It will pass.”

Don’t worry? My dad was convulsing. He looked like he was going to die.

No one ever told us about PTSD. The term was not even a term back then. It was the 1950’s, and later the 60’s. My generation only knew that our dads had fought in “the war,” and that now they were home.

In fact, my dad loved to watch World War II movies. We watched them together ritually, just as we watched football games. I knew he hated the Nazis, and I was glued to the screen. As I got older, I started asking questions.

He said that after Pearl Harbor, he volunteered for service in the Army. He had just finished dental school and didn’t have to go, but it was not something he could personally avoid. My dad enlisted and was placed in the 77th Division, later to be known as the “Bloody 77th”, and he was sent to the Pacific Front.

He told me that he was made a medic, even though he was a dentist. They needed doctors. But he also said that he never took the lock off his gun because he was afraid of killing someone, even in a division that lost more men than almost any other brigade in the Pacific.

My father lost all of his friends. Everyone between Guam, Leyte, Okinawa and all the other islands...gone. His feet were never cured of jungle rot.

He told me how terrifying it was waking up in the mud to gun shots, bombs, never knowing where he was. . .

My father joked that he would make deals with naval commanders, trading a day of dental care for food and scotch to bring back to his buddies (he said the Navy always had more supplies than the Army). It sounded like M.A.S.H. and I suppose it was. Then he told me how terrifying it was waking up in the mud to gun shots, bombs, never knowing where he was or where they would be going in the dark jungle night, stumbling around in the wet weeds. And how frightening it was carrying a heavy backpack when they had to slither down the side of a tall battleship in the night. My dad’s longstanding fear of heights began to make sense to me. So did his exaggerated startle response when he woke from a Sunday nap.

One day my mom was cleaning out his dental cabinet and I noticed a bronze star. Find me the kid who doesn’t like medals! I asked my mom where it came from, and she told me to ask my dad.

“So we were in a fleet somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, headed from one island to another, and the Japanese attacked by air. A number of boats sank, and ours was one of the only ones left afloat. There were many casualties, and all were brought aboard. I was the only medic. I had to stop bleeding, sew guys up, and rally my boys to help. We saved a bunch of lives, but lost many.”

“But Dad, you’re a dentist!”

“I know. Just my luck. Go figure.”

My dad had a great sense of humor. I guess it runs in dentists. You know, they have captive audiences for their jokes, and how can you complain with all that cotton in your mouth? When he took the cotton out, he usually asked his patients to tell their favorite jokes (often dirty ones) and he kept the best ones to pass on to others.

It turned out his dental books were translated into Japanese. He even made a number of wonderful friends there, visiting often as a guest lecturer and beloved colleague. It was puzzling to me that he held no grudges against the enemy. At least not with the Japanese.

War was war, he’d say. And, hey, he was on the way to Tokyo when the bombs dropped. While he was grateful for the end of the war, he knew the devastation that resulted.

Still, even though he and mom traveled all over the world, he always refused to go to Germany. It was too much, having grown up as a Jew, the son of Russian immigrants – even a secular Jew. I wonder how he would have lived through the horror of the war if he were on the Western Front instead. His PTSD would have probably been much worse.

Look. My dad suffered from PTSD his whole life. Nothing substantially changed. We all learned to live with it, and so did he. Thankfully, he was not incapacitated, and enjoyed a productive life as a dentist, teacher, father and friend. He took great care of his patients and they loved him. But the war made a mark on him and on all of us.

And I still love watching war movies. They make me think of my dad.

We understood malaria and foot rot. They were medical problems brought home from the war. But the symptoms of PTSD were really scary and baffling. While he suffered, he accepted his condition as just the way he was. Nothing more, nothing less. I do wonder now if he'd gotten treatment whether it would have made a difference. Perhaps. But he’d never see a shrink – not for this. I’m not sure if it was the stigma, or just not what WWII vets did. It was not even an option for consideration.

As I look now at the challenges facing our nation, I understand that I was lucky to be the kid of a vet who did not suffer like many of our veterans do. Unfortunately many brave men and women are suffering terribly, and that suffering is made worse by the stigma inherent in having a psychiatric disorder. Even PTSD, a well recognized and accepted syndrome, brings with it shame and prejudice. Hopefully now that we know more about this disorder, its impact on families, and its treatment, others will get the help they need.

I’d like to be able to say that to my Dad if he were still around.

Gene Beresin, M.D. is executive director of The Clay Center for Young Healthy Minds, and a child and adolescent psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital. He is also a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Follow him on Twitter, @GeneBeresinMD, or email him at gene@mghclaycenter.org.

This program aired on November 11, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.