Advertisement

Caution: 'Acceptable' Black Women's Hairstyles May Harm Health

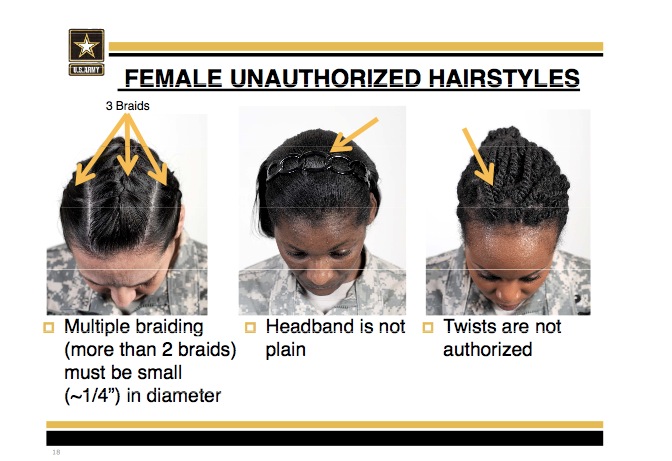

This spring, the Pentagon issued Army Regulation 670-1, which included bans on several hairstyles worn mainly by black women, including twists and multiple braids. After a major backlash that included accusations of racial bias, that grooming policy is now under review. Here, researchers at the Connors Center for Women’s Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital argue that this is more than an issue of racial fairness; it could also cause harm to women's health — and disproportionately impact black women, whose life expectancy is already five years less than white women's.

By Tamarra James-Todd and Therese Fitzgerald

Guest contributors

We are encouraged by the news that the Pentagon is reviewing the Army’s grooming policy, Army Regulation 670-1, which many deemed to be racially biased because it banned hairstyles worn primarily by black women.

Such policies set unreasonable standards for what is appropriate or acceptable in our society, and promote the idea that natural “black” hair is somehow inappropriate and unacceptable.

But perhaps most disturbing is the growing evidence that the process involved in straightening curly hair and maintaining acceptable hairstyles is harmful to women’s health, disproportionately affecting black women and making the pervasive practice of banning “black” hair styles a major health equity issue.

Nearly half of black women and girls use hair products that contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals compared to just 8 percent of whites.

The military’s previous position on this reflects a precedent that unfortunately continues to exist in corporate and private sector settings throughout the country. Labeled as “grooming” issues, companies have fired employees for wearing dreadlocks and a private school in Orlando, Florida, threatened to expel a young girl if she refused to straighten or cut her natural black hair.

The public discourse around these biased policies should not only focus on the racism they perpetuate but also on the potential harmful health outcomes and health disparities they may leave in their wake now and for future generations.

In order to conform to the standards of appearance that these policies demand, black women and girls are often encouraged to straighten or otherwise change the texture of their natural “black” hair. Unfortunately, many of the hair relaxers, oils, creams and other products used to straighten or alter curly hair contain synthetic chemicals that disrupt the normal functioning of the human body’s endocrine system, which regulates and secretes hormones.

Based on hair product labels, nearly half (49 percent) of black women and girls use hair products that contain endocrine-disrupting chemicals compared to just 8 percent of whites, which could leave blacks with higher levels of these chemicals in their bodies compared to whites.

For example, phthalates, a class of endocrine-disrupting chemicals used in hair products, are known to be found at higher levels in blacks than whites. Research led by Dr. Tamarra James-Todd at the Connors Center for Women’s Health at Brigham and Women’s Hospital has revealed that higher phthalate levels are associated with a variety of poor health outcomes that disproportionately impact black women and girls including:

•Type 2 diabetes, a condition twice as common among black women compared to white women, as well as insulin resistance and other associated conditions.

• Gestational diabetes, a form of diabetes that occurs during pregnancy that has negative implications for both mother and child health, including a higher likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes as well as cardiovascular disease, which affects twice as many black women as white women.

• Early-onset puberty (i.e., early breast development and early-onset menstruation), more common in black girls compared to white girls. Use of hair oils, many of which contained these synthetic endocrine-disrupting chemicals, presented a 40 percent increased risk of early onset of menstruation, a risk factor for breast cancer and metabolic diseases.

Research by others has shown that phthalate levels are associated with additional negative health outcomes, including:

• Preterm birth, with rates in the U.S. 60 percent higher in black women than in whites. Preterm birth is associated with increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in mothers and greater risk of mortality, breathing problems, cerebral palsy and developmental delays in infants.

• Fibroids, a condition two to three times more prevalent in black women than white women. Fibroids can lead to uterine bleeding, pelvic pain, severe symptoms requiring hospitalization and major surgical interventions including hysterectomies — the latter is twice as common in black women as white women.

• Childhood obesity, which is 40 percent higher in black children compared to their white peers. Obesity in children places them at increased risk of a variety of metabolic conditions, including type 2 diabetes in youth.

Today, a black woman’s life expectancy is five years less than a white woman’s. More research is needed to determine whether exposure to hair products containing these chemicals is a major contributor to these health disparities, but the evidence that already exists should inform the decision-making of consumers, policy-setting organizations, and the prevailing culture.

Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, MPH, is an Associate Epidemiologist at Brigham and Women's Hospital and an Instructor in Medicine at Harvard Medical School. Therese Fitzgerald, PhD, MSW, is Director of the Women's Health Policy & Advocacy Program for the Connors Center for Women's Health and Gender Biology at Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Readers, thoughts? And if you're wondering about the chemical content of a particular hair product, there doesn't seem to be any one source that gathers all that information (please correct me if I'm wrong) but the Environmental Working Group offers a database of risk assessments on many cosmetic products, including hair care, here.