Advertisement

'Not Just Lyme Disease Anymore': 7 New Reasons To Fear Ticks This Summer

A father of four boys, Michael Vitelli of Marshfield Hills, Mass., lives a high-energy, outdoor and active life when he's not at work. He fishes, he hikes, he golfs, he can even boast a running streak of 642 days in a row.

But last month, on what would have been day 643 of running, a tick brought him to an excruciating halt.

After feeling achey for a few days, Vitelli suddenly got too sick to get out of bed, as if with a summer flu — fever, sweats and chills, headache. Then he got even sicker. His test results looked dire: protein and bile in his urine; liver function gone haywire; platelets, red and white blood cells down so low that his chart looked like he had leukemia, a doctor told him.

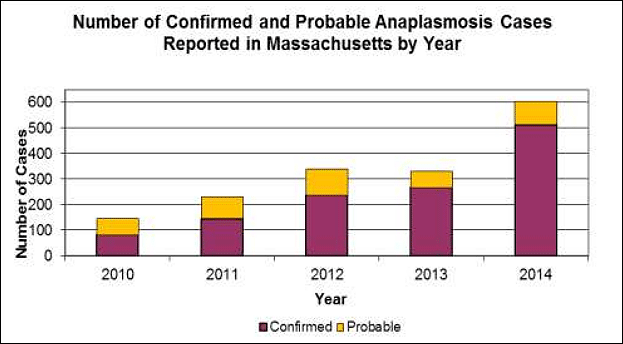

The diagnosis, after three days in the hospital: anaplasmosis, an infection borne by the same deer ticks that carry Lyme disease. It's up dramatically in Massachusetts: About 600 confirmed and probable cases statewide last year, compared to closer to just 100 in 2010.

Never heard of it? Neither had Vitelli. Naturally, he'd heard of Lyme, which has spread across much of the country in recent decades and now infects an estimated 300,000 Americans a year at least, mainly in New England and the Midwest.

But like most people, he didn't know that ticks can carry a whole array of nasty bugs — with obscure names like babesiosis and Borrelia miyamotoi — and that, though much less common, they, too, are on the rise, following more slowly behind the inexorable march of Lyme disease.

In worst-case scenarios, some of these infections can kill people, usually those who are old or have an underlying condition. Deaths are very rare; what's not rare is for patients to get much more acutely, severely ill than is typical for Lyme disease.

"Those little ticks," Vitelli says with the voice of bitter experience. "They can really wreak havoc with the body."

It's peak season for Lyme disease right now, and for these other infections as well. If the risk of Lyme hasn't been enough to prompt you to take the recommended measures against ticks — repellent, tick checks — perhaps awareness of these rising new risks will add impetus. Public health officials also call for vigilance about persistent summer fevers with no other obvious explanation, and for greater awareness that they can be caused by bugs other than Lyme.

"If you live in an area where there's Lyme disease, you should be aware of these other agents," says Dr. Peter Krause, a tickborne disease expert at the Yale School of Public Health. "And that's true throughout the United States."

Advertisement

It's also true for doctors. "If you're thinking about Lyme disease, you should think about these other diseases, too," says Dr. Larry Madoff, director of epidemiology and immunization at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, who recently helped treat a case of anaplasmosis in central Massachusetts. "And even if you don't see Lyme disease, if you have a patient who reports tick exposures or lives in an area where there's a high prevalence of these diseases, you should think about these as well. And they are treatable," with antibiotics.

At the risk of being accused of scaremongering, here are seven new reasons to fear, loathe and avoid ticks more than ever this summer, based on news about these more acute infections:

1. Pronounced me-ya-moe-toe-eye:

Researchers keep finding new tickborne bugs, like Borrelia miyamotoi, which was first reported in 2013 and causes flu-like feverish illnesses so severe that a recent study found that about one-quarter of patients who tested positive for it had landed in the hospital.

About 14 percent of patients who had it also tested positive for the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. The findings suggest that Borrelia miyamotoi "may not be a rare infection in the northeastern United States," the authors write.

2. No Relaxing In August

An editorial co-authored by Dr. Krause that accompanies that study begins with this punch: "It's not just Lyme disease anymore."

It notes that "the peak incidence of positive assay results for B. miyamotoi was in August, with probable onsets of illness continuing into September, which is about a month after the peak incidence of Lyme disease."

That timing suggests that ticks still in the larval stage are the culprits: "Bites from larval deer ticks have not been considered as a health threat, but this needs to be reevaluated."

In other words, even tick babies are bad. And the period of peak tick vigilance may need to be extended from summer into fall. (Already, some ecologists are calling for heightened tick vigilance in the Northeast earlier in the spring, starting in April.)

3. Going Where Lyme Goes, But Later

The ecological backstory of the rise of tickborne bugs, Dr. Krause explains, is this: As the forests returned to New England in the 20th century, so did the deer, and with the deer came infected ticks. Lyme disease is transmitted more readily than the other infections, and it can be carried by birds, he says, so it spreads faster.

Dr. Alfred DeMaria, medical director for the Bureau of Infectious Disease at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, singles out the white-footed deer mouse as another culprit in the infections' spread. In the springtime, he says, young "nymph" ticks are out infecting the mice with the bacteria, and the rodents amplify the infection rates.

"There are more and more of these mice in the fragmented forest environment that we've created," he says, "through the suburbanization of the state. And now we're seeing the consequences of that."

Bottom line: If you're in an area with Lyme — and that means all of Massachusetts and much of the Northeast from Virginia to Maine — other infections are likely.

4. In The Blood

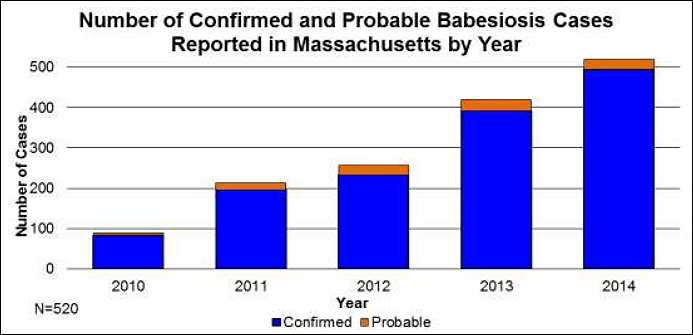

Also to be filed under "tick infections that are not so rare anymore": babesiosis. The rise in its prevalence looks very similar to anaplasmosis:

It is the No. 1 infection spread by blood transfusion in the United States, Dr. DeMaria says, to the point that the FDA is expected to recommend screening blood from high-prevalence states like Massachusetts for it, and possibly the entire national blood supply.

5. Climate Change

You knew this was coming. Among the countless other problems it's creating, climate change is extending the habitats of ticks and thus of the infections they carry. Case in point: The Vineyard Gazette on Martha's Vineyard cites multiplying reports of Lone Star ticks on the island this year. Lone Star, that is, as in Texas. Under the headline "Lone Star rides into town," it reports:

While it’s premature to say if the Lone Star tick has colonized on the Vineyard, anecdotally and on social media, many Islanders have reported finding them for the first time this year...Unlike deer ticks and dog ticks, the Lone Star tick is an aggressive predator. “They’re nasty; they have eyes, unlike deer ticks that are blind,” [tick biologist Sam] Telford said. “They can see you and come after you.”

...

Until recently, the Lone Star tick was primarily found south of the Mason-Dixon Line. But as the climate has warmed, the infectious insect has spread its range. The Lone Star tick has now colonized on Cuttyhunk, Nashawena, and Prudence Island.

Lone star ticks carry quite a few diseases, Dr. Madoff notes, among them Ehrlichiosis, tularemia, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. (Massachusetts just had a case of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, he says, though it's not known which tick spread it.)

6. Scariest Of All

I recently asked Dr. Harriet Kotsoris, chief scientific officer of the Global Lyme Alliance, what scares her most in the world of tickborne infections. Her reply: Powassan Virus.

It remains exceedingly rare — only about 60 confirmed cases nationwide over the last decade — but, she says, it's like equine encephalitis in that it "has a predilection for the central nervous system, and it carries a 10 percent mortality rate."

And unlike anaplasmosis or babesiosis, which respond well to antibiotics, it has no treatment.

There have been about five cases in Massachusetts since 2013, the Worcester Telegram reports.

And here's the worst part: It's generally thought that the Lyme disease bacterium infects a person only if the tick has been feeding on them for at least 24 hours; Powassan is believed to need only 15 minutes.

7. Even The Healthiest

Though the more acute tickborne infections tend to kill people who are older or physically weaker, they can hammer even the healthiest.

The ultimate cautionary tale comes from Dr. David Katz, director of the Yale University Prevention Research Center and president of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine. He's one of the country's leading voices on the medical importance of healthy behaviors like good diet and plenty of exercise, and he practices his preachings in his personal life in woodsy Connecticut, from horseback riding to hiking to gardening.

So it was a shocking departure from his usual wellbeing when he fell desperately ill last month. "I became so sick that I couldn't lift my head off the bed, I could barely turn my eyes," he recalls. "I had shaking chills, drenching sweats, crushing headache."

Like Michael Vitelli, Dr. Katz was diagnosed with anaplasmosis. He writes about the experience here, and he says that though he had long practiced Lyme disease prevention, "this was a bracing reality check for me, too, because this was a serious infection. I haven't been this sick — well, I never have been this sick, frankly, and I don't want to experience it again any time soon."

Dr. Katz sees multiple lines of anti-tick defense — covering up outdoors, showering when he comes indoors, checking for ticks --but he says it's also important "to recognize that those defenses are imperfect, a tick may slip through, and if you start to get characteristic symptoms, get checked out."

Michael Vitelli, too, emphasized the importance of knowing your body and seeking prompt help when something feels really off. And his experience made him wonder, he says, what's being done to eradicate ticks.

Not much, according to a report this April by the New England Center for Investigative Reporting: "Despite Spread of Lyme Disease, Mass. Dedicates No Money To Prevention."

It remains to be seen whether the rise of potentially fatal tickborne infections will affect that policy — or rather, that lack of policy.

Readers, thoughts? Reactions? Experiences?

Deep thanks to the other listeners who answered WBUR's call to hear from people who'd recently experienced non-Lyme tickborne infections. We heard from a half-dozen within hours of our Facebook post — further testament that these diseases have become less rare.