Advertisement

State-Funded Lab At Harvard Medical Aims To Reinvent Drug Discovery

Resume

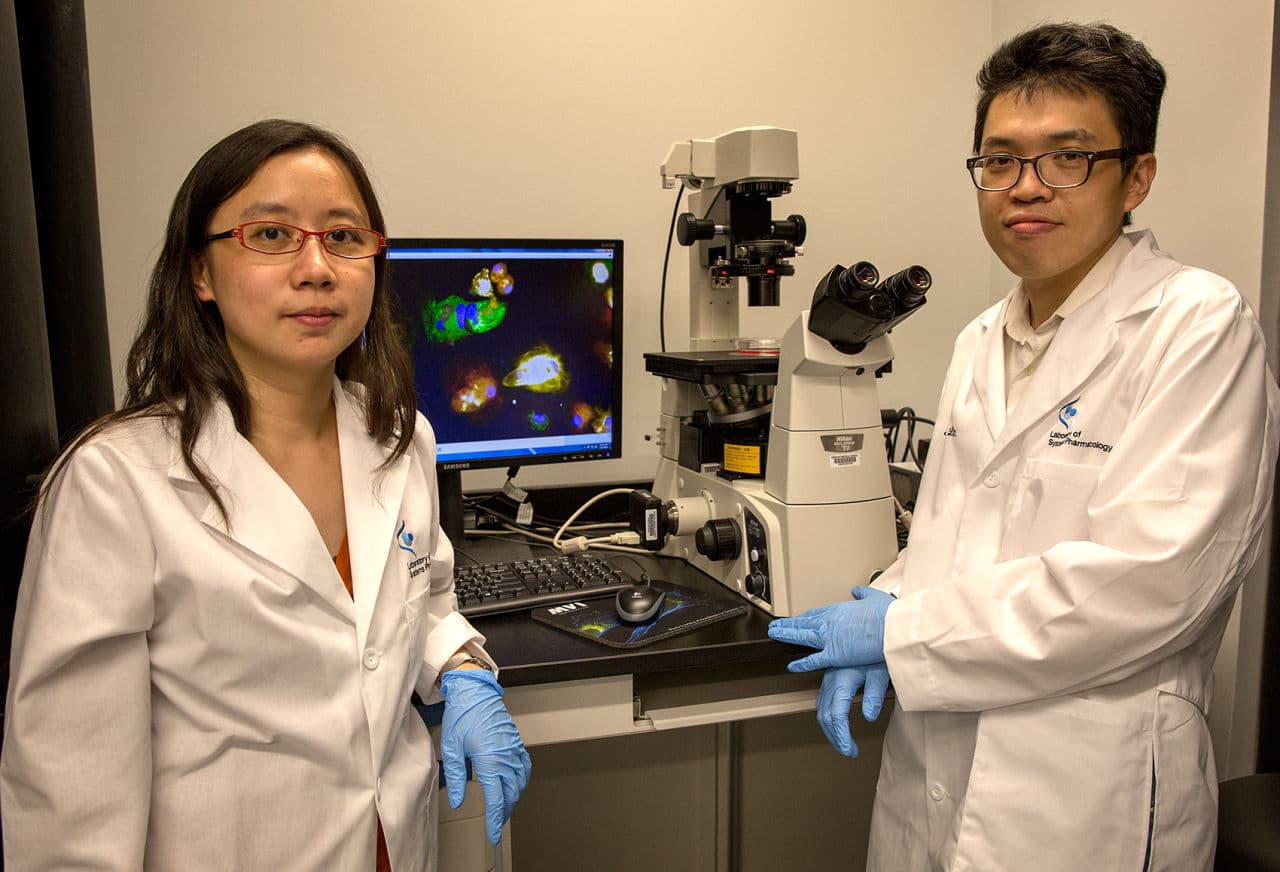

Jerry Lin makes a few adjustments on his microscope and grins.

"Wow, it's beating," Lin says as a white cell floating across an inky black background begins to pulse. "That’s cool." A few colleagues, including Lin's lab partner, Sharon Wang, murmur approvingly.

"We want to take a real-time video to look at the pattern of how cells beat over time," Wang says, explaining this stage of the experiment.

Once Lin and Wang understand the morphology of these heart muscle cells, they'll test how the cells respond to various cancer treatments.

"Later on, we can look at how that frequency of beating responds to different drugs," Wang says.

The experiment is important, says lab director Peter Sorger, because heart problems can be a side effect of a drug that stops the spread of breast cancer.

"On the one hand, it’s a marvelous magic bullet," Sorger says. "On the other hand, it does damage on its way in. So the purpose of these studies is to understand precisely why that happens."

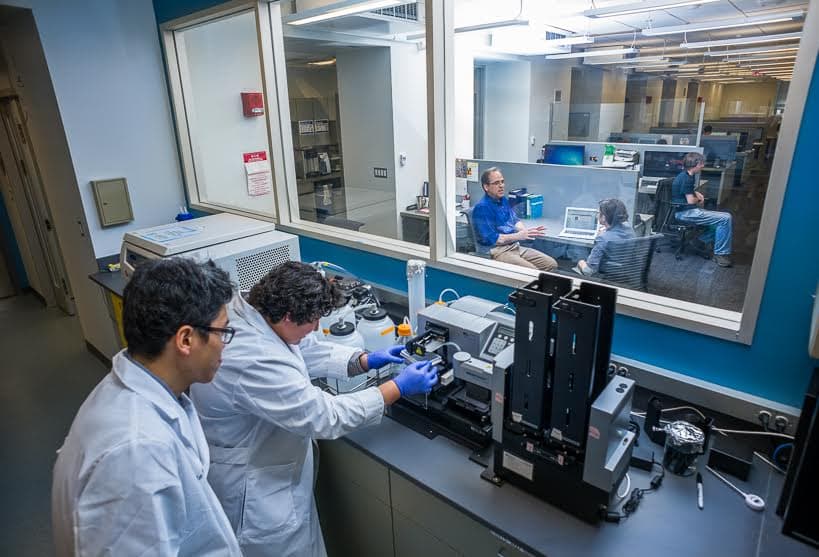

Sorger and his team at the Laboratory of Systems Pharmacology are focused on cancer and on analyzing the ways cancer drugs affect the whole body. They aim to reinvent the drug development process through this systems approach, by going much deeper than would scientists supervising a typical clinical trial and by establishing a new model of collaboration.

The lab staff is an unusual collection of investigators. They come from four hospitals and three universities: Harvard, MIT and Tufts. The scientists are a mix of wet bench biologists like Lin and Wang, physicians and PhDs who build complex mathematical and computer models. That mix is one of the main reasons the Massachusetts Life Sciences Center provided $5 million to construct the lab.

"They’re not just using science, they’re using mathematical modeling, and this has the potential to really, really accelerate how we go about discovering drugs," says Susan Windham-Bannister, the immediate past president of the Life Sciences Center.

Windham-Bannister says the lab will analyze massive amounts of data, finding possibilities that would not be apparent in the linear steps of traditional drug development. Running data, she says, may be more informative than tests on a small number of study participants.

"Maybe everything doesn’t have to be done using human subjects. Some of these things can be modeled using existing data. That’s a very novel resource," Windham-Bannister says.

Especially now, adds Sorger, with volumes of human genome information available to help predict how a drug would work, or not work, for individual patients.

"The practical impact we could have is in making cancer drugs dramatically more effective in the right patients and also making them available for diseases that we can’t currently treat," Sorger says.

If drugs are only given to the patients they will help, and not to patients likely to experience harmful side effects, Sorger says the cost savings and improvements in care could be dramatic.

"Much of what we’re trying in the lab are the things that are getting left undone, that year after year are not being addressed because of a lack of investment, a lack of training, a lack of long-term perspective."

Peter Sorger, the lab's director

There has been some grumbling about the award to Harvard. Did one of the nation's wealthiest universities really need the state’s $5 million to launch this project?

"We really were assured by the team that applied for the grant that the medical school was not in a position to provide the funds," says Windham-Bannister, who adds that the state's investment has already brought in $30 million in federal research grants for the lab.

It's a wise investment of public funds, says Joshua Boger, who founded Vertex Pharmaceuticals and now chairs the board at Alkeus Pharmaceuticals. He was an early supporter of the Harvard lab.

"Our largest fiscal challenges of the next 50 years will be dealing with diseases like diabetes, cancer, and Alzheimer's, that could bankrupt the country if we do not find better treatments. Public dollars are well spent creating better methods of studying these complicated diseases," Boger wrote in an email response to questions.

The lab will collaborate with the pharmaceutical industry. It will also take on projects that may not be profitable: dissecting the reasons so many drugs fail during clinical trials and reviewing the effectiveness of generic drugs that have been on the market for years without further testing.

"Much of what we’re trying in the lab are the things that are getting left undone, that year after year are not being addressed because of a lack of investment, a lack of training, a lack of long-term perspective," Sorger says.

The lab's research, funded by public dollars, must be shared in the public domain, but it may have special significance in Boston's biotech supercluster.

"The Boston area represents the hub of life sciences on the planet," says Ken Kaitin, director of the Center for the Study of Drug Development at Tufts University School of Medicine. "By putting this in the Boston area, you immediately attract the attention of local academic institutions, a lot of start-ups that are getting involved in drug development and many large companies that are now putting facilities in the Boston area. There are investors here who are interested in seeding new companies. The Boston area is the ideal place to launch this."

Kaitin says more and more companies are relying on academic institutions to do the fundamental science of drug development and institutions are relying on industry to make up for the loss of government research grants.

Meanwhile, patients advocacy groups are watching to make sure that the public investment in the Harvard lab results in drugs that are cheaper and increase the chance of surviving diseases, like cancer.

This article was originally published on August 10, 2015.