Advertisement

A Cultural Shift For Doctors: Asking Patients 'Why?'

Resume

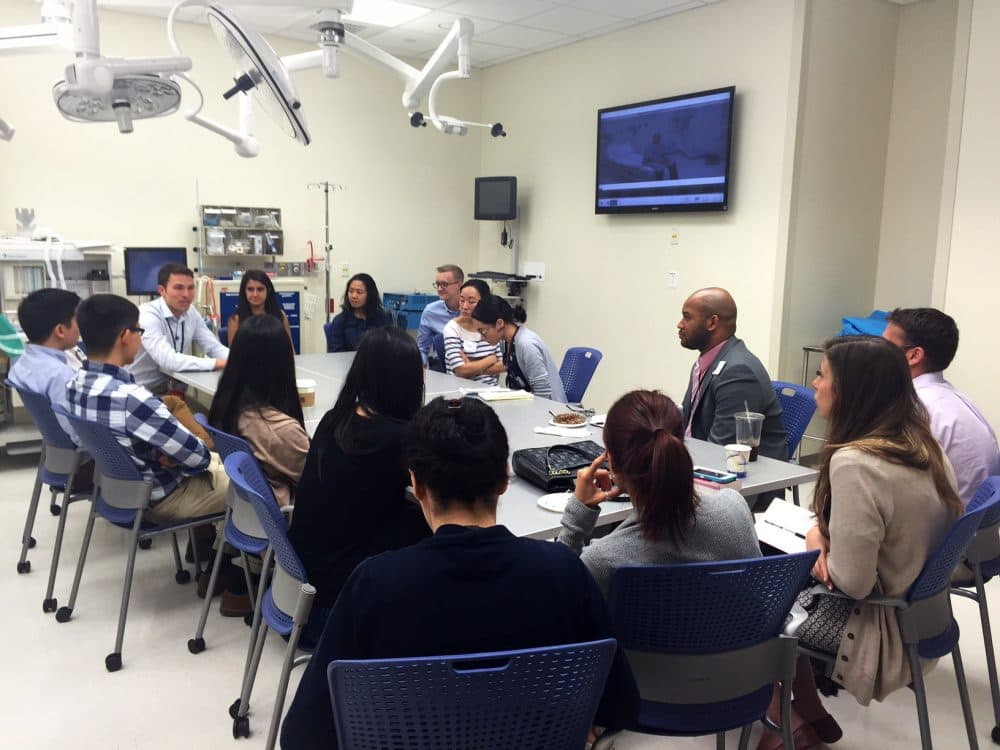

Fourteen young men and women shift their chairs toward a screen on a conference room wall at Boston Medical Center (BMC). As the video begins, a resident in green scrubs walks into an exam room and greets a man slumped on the edge of a hospital bed.

The patient has a throbbing headache. He says he comes to the ER with the same problem about every two months. He doesn't have any medication for headaches, but he does have a prescription for his high blood pressure.

"How often would you say you take this medicine?" the resident asks. "Whenever I can," the man says with a shrug. "So how often, is that?" the doctor asks. "When I can," the man repeats.

The resident checks the patient’s heart rate, breathing, balance and some other things, then excuses himself to consult with a senior emergency room doctor. The video ends.

"What was lacking, what was missing in that interaction?" asks Dr. Travis Manasco, a fourth-year resident who’s leading this workshop. His new colleagues noticed the doctor did not sit down, a common clinical faux pas. He asked yes or no instead of open-ended questions. Josh Minsky points out the resident didn’t find out why the patient isn’t taking his medicine as prescribed.

"He didn’t really kind of delve in at all, like why can’t we get the med in you on a normal schedule, what’s the problem, try to evaluate that a little bit," Minsky says.

"I agree," Manasco says with a nod.

Asking Better Questions To Better Patients' Health

This is day two for new residents at BMC. This year orientation includes a workshop on what's known as social determinants of health. It’s a recognition that where and how people live, their cultural or religious beliefs, their education and income — all these things affect health.

The pediatrics department at BMC has included a similar simulation for residents for several years. Dr. Jeff Schneider, who oversees training programs at BMC, added this workshop for all new residents to emphasize the need for a cultural shift among doctors.

"As important as checking their blood pressure is probably trying to figure out why their blood pressure is poorly controlled," Schneider says of patients. "It’s as important as anything else you’re going to do."

In the conference room, the second of four videos begins. A senior emergency room listens to the resident’s summary of his patient and has some questions.

"OK, I was just wondering, why is his blood pressure out of control?" the attending doctor asks.

"He's noncompliant," the resident says.

"Why is he noncompliant?" the attending asks.

"Why is any patient noncompliant?" the resident responds, showing some frustration. "He’s supposed to be taking Amlodipine [a blood pressure medication] and uh, and look at his encounter history -- no show, cancelled, no show, no show."

"But why?" the attending asks, again.

"I don’t know," the resident says throwing up his hands.

That’s a response the organizers of this workshop do not want to hear any more. When asked "why," the patient says he often has to choose between paying for his medication and feeding his kids. He misses appointments when they conflict with work.

Breaking Away From 'Fueling That Cycle' Has Challenges

But do doctors have the time to ask about such problems and can they fix them?

"It feels like we don’t have the tools for that, even though we probably do at this hospital," says Katrina Ciraldo. "It's just easier as a resident, when we're trying to get to our next patient, to avoid that stuff that seems like it takes a long time, but it's really the driver of the health care outcomes."

"I think it’s also unclear or maybe there’s a fuzzy line between things we should be trying to tackle on our own and when we should ask for help," says Michelle Zhang.

"Once you open up that door, there's a lot of resources," Manasco tells Zhang. "Never be afraid to ask for help."

Boston Medical Center, the largest so-called safety net hospital in New England, has a food pantry, legal aid, housing assistance and a dozen other programs that are outside the scope of traditional health care. But even at BMC, would every supervising physician ask a resident to find out why a patient isn’t taking their medicine?

"Nope, not at all, but it won’t be long before this thing will catch on," predicts Dr. Thea James, the hospital's vice president of mission and associate chief medical officer.

James created this workshop after years of seeing patients return to the emergency room at BMC even though doctors had sent them home with an appropriate prescription or treatment plan.

"We can always, more often than not, fix the blood pressure or whatever brings you here," James says, "but if we send you back to what caused it without ever finding out what caused it, we are just fueling that cycle."

Most medical schools and residency programs focus on the biology, not the sociology, of health, but that is shifting. The new Dell Medical School in Austin, Texas says students will form deep connections in the local community. Johns Hopkins started a 12-workshop series for residents called "Medicine for the Greater Good" in 2011.

"Every resident should be aware of social determinants of health," says Dr. Sammy Zakaria, a cardiologist and assistant professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins. He says it's time for doctors to move "outside the traditional model where a patient comes to the doctor's office, get pills and lab tests and then leaves."

Paying for housing or food or violence intervention or rodent control as a health care expense is still unusual, but "that's evolving in terms of payment reform," James says. "It's moving at a pretty good pace."

Nurses may be a few years ahead of doctors when it comes to training the profession to incorporate a patient's social setting into a health care plan. A requirement that nursing schools teach students to assess cultural factors that affect health started in 2008.

"There are so many different ways that the system works against people who are of different social classes," says Judith Shindul-Rothschild, an associate professor at the Boston College School of Nursing. "So our students have to, right from the start, do a nursing assessment that takes all of these factors into account."

James says hospitals should incorporate training in social determinants of health for all personnel.

"That way we know that everyone comes in drinking the Kool-Aid," says James, so that "everyone understands the purpose and culture and will think through that lens and see things through that lens and will hopefully act through that lens."

This segment aired on July 7, 2016.