Advertisement

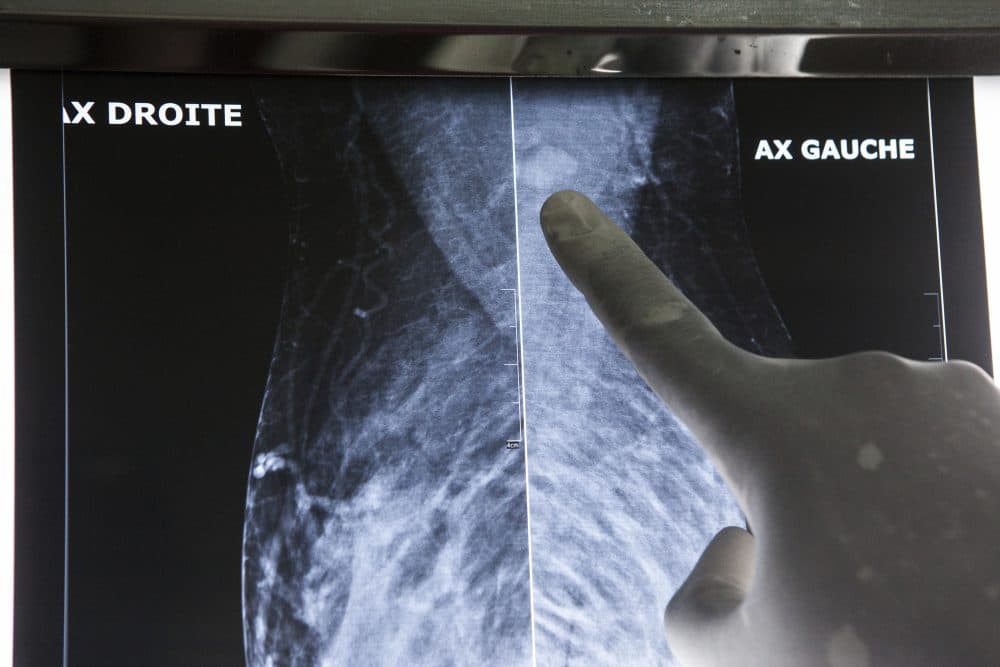

Standard Age For Mammograms Puts Nonwhite Women At Risk, Study Finds

At a 2016 conference in Japan, Dr. David Chang happened upon data showing that Japanese women tend to get breast cancer in their 40s. The figure surprised him, because the American group of experts who recommend policies on cancer screening had recently upped the age for routine mammograms here to 50.

Then, Chang, an associate professor at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, was invited to a conference in Mexico. And there, he saw the same trend among Mexican women.

Back home, he and colleagues checked the federal database on cancer incidence and survival. They examined records from Jan. 1, 1973, through Dec. 31, 2010, and tracked the age at breast cancer diagnosis for 747,763 women, most of whom were white.

They found that breast cancer diagnoses among white women peaked in their 60s --supporting the task force’s decision to start screening at age 50.

But the story was different for black, Hispanic and Asian women. In a study published Wednesday in JAMA Surgery, researchers led by Chang showed that the nonwhite women tended to get breast cancer in their 40s – a full two decades earlier than whites, and too soon to benefit from the mammograms begun at age 50.

I spoke with Chang about his results and their implications. What follows is an edited version of our conversation.

So, your conclusion is that there shouldn’t be a universal screening age?

It wouldn’t make sense to have the same screening age for everyone.

Why has it taken so long to figure this out?

Why is it no one ever bothered to think about asking the question whether or not these findings could be generalizable to other populations?

Researchers just assumed that what was true for whites was true for everyone?

The white population is the exception rather than the norm. But I think we have the subtle assumption that what is seen in the majority is the norm.

We tend to blame doctors for race-based disparities in health, but what you’re saying is that nonwhite patients would be at a disadvantage even if there was no prejudice among doctors?

If [doctors] follow the guidelines, they would be screening their patients way too late. It’s not a delivery problem. It’s a science problem.

Flawed science may actually cause more harm than flawed care.

You said this is only one example of a larger trend where the assumptions of majority scientists affect medical care. Can you offer another example?

When men dominated fertility research, infertility had always been blamed on women. But when women started getting into the field, they realized that men actually have issues as well.

Do you see a solution?

If science isn’t as objective as we think it is, then diversity [among scientists] is important because we need to have more people to bring in their biases and perceptions into the process, so people will look at this and say ‘Hey, this doesn’t make sense!’