Advertisement

Commentary

About That Heart Device Your Doctor Recommends: Are You Sure You Understand The Risks?

Let's say you're one of the nearly 7 million Americans with heart failure.

Your heart’s ability to pump blood is impaired. Despite being on all the right medicines, at doses as high as you can tolerate, your quality of life is getting worse. You’re comfortable at rest, but you get short of breath with even mild exertion, and you feel weak and tired all the time.

Your cardiologist says, "Ideally, it would be time to think about a heart transplant, but you have other medical issues that would make you a less-than-ideal candidate. So I think it’s time for you to get an LVAD."

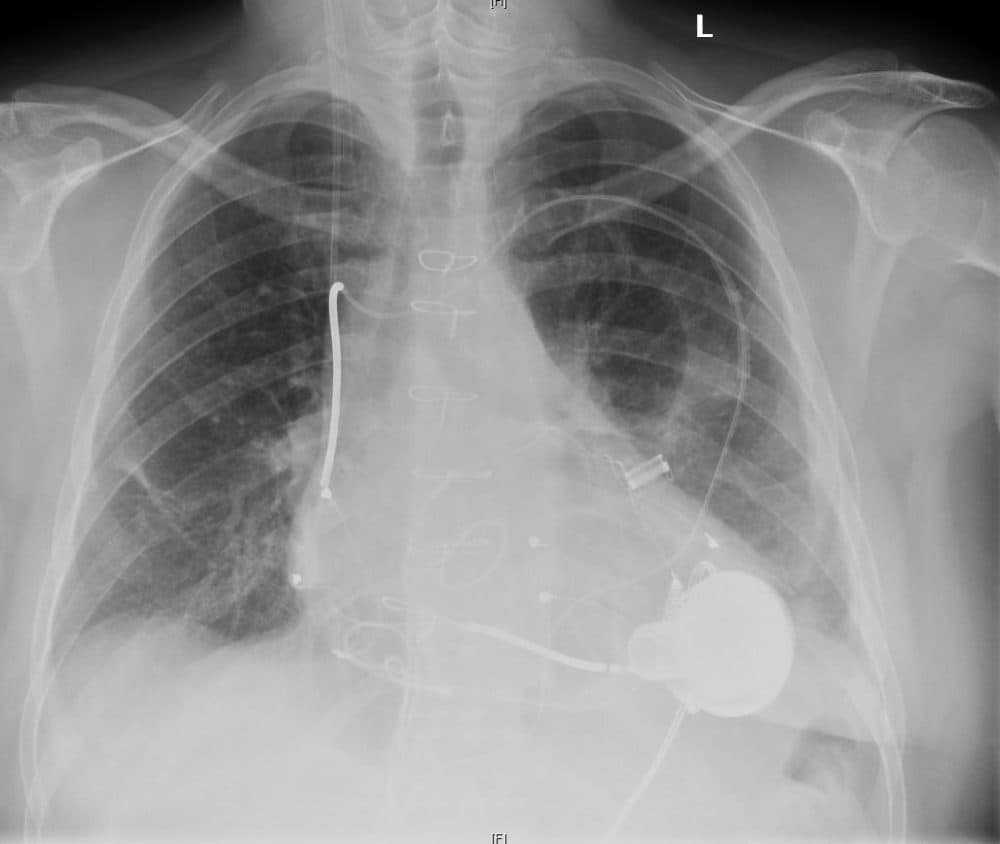

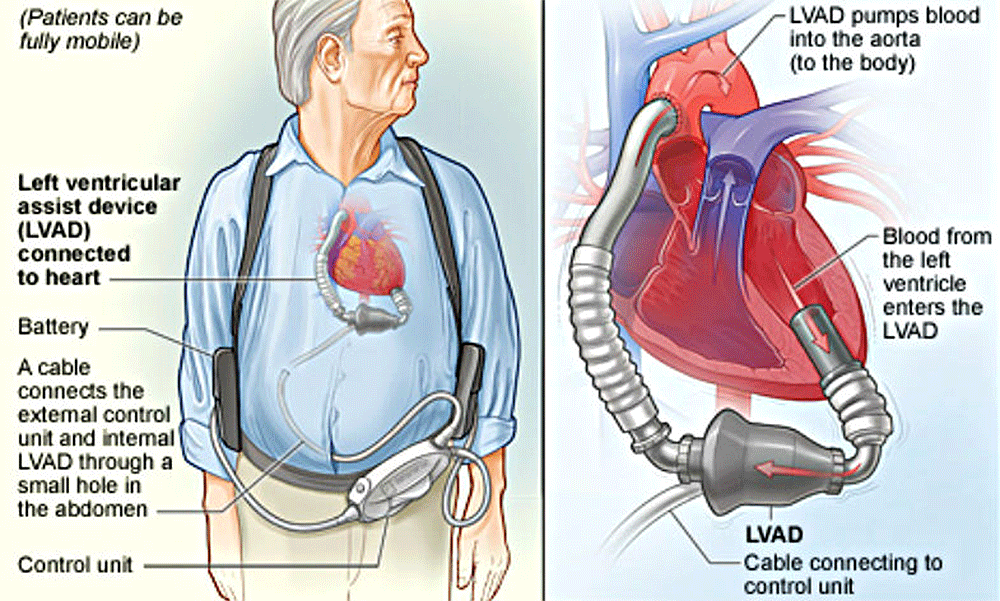

LVAD stands for left ventricular-assist device. It's an electrically powered pump implanted surgically between the left ventricle and the aorta to bolster your failing heart’s ability to provide blood flow to vital organs.

The stats sound good. Overall, LVADs save lives and improve the quality of life for many heart failure patients. But these benefits come with a high rate of possible complications that include stroke, bleeding, infection and pump failure.

That’s a lot to process, and it's up to the doctor to convey the complex information you need clearly enough for you to be able to make a fully informed decision.

Unfortunately, we doctors are not doing a great job of that, a recent study suggests — because if we were, fewer patients would be choosing to have these devices implanted.

Lowering The Bar

When they were first developed, LVADs were used only in patients with the most advanced disease, those with heart failure so severe as to require using drugs that stimulate the heart to contract more forcefully — known as inotropic agents — while the patient was put on the waiting list for a heart transplant.

These drugs, when given continuously over long periods of time, increase the likelihood of sudden cardiac death, so they’re usually used only when a decent quality of life can’t be maintained without them.

In patients with such severe disease, the likelihood of surviving — and the quality of that survival — was found to be much higher with LVADs than with available medications.

Based on this success, the practice of implanting LVADs was extended from "bridge-to-transplant" therapy to "destination" therapy for patients with end-stage heart failure whose age or other medical problems made them poor candidates for heart transplants.

More recently, LVAD use has expanded to patients with heart failure that is severe, but not severe enough to require support with inotropic agents. Among these patients, those with LVADs do better, a study last year found: Symptoms improved significantly in 69 percent of the patients who received LVADs, compared to only 37 percent of those on drugs alone. At the two-year mark, the patients with LVADs were more likely to be alive.

Now For The Bad News

Having worked as a cardiologist in my university’s advanced heart-failure program for 16 years, I can attest to the huge benefits many patients derived from their LVADs. It's been common for a patient tell me, "I feel a thousand times better since the LVAD was put in." I've even seen reports of younger patients who did so well they could have their LVADs explanted, or removed.

But there’s more to the story, and it’s sobering — particularly for those patients who are not in dire need of a transplant:

• LVAD recipients need to be on lifelong medications to prevent the formation of blood clots within the pump, and problematic bleeding occurs in more than half of them, versus just 3 percent of medically managed patients.

• Worsened failure of the right ventricle — which can leave you worse off than you had been — occurs in 11 percent of LVAD patients, compared to only 3 percent of those on meds alone. A common cause of sudden cardiac death — ventricular arrhythmias — occur in 22 percent of LVAD recipients, versus 13 percent of medically managed patients.

• Infections of the cable that connects the external electrical power source to the internally placed pump occur in 17 percent of LVAD patients, and clotting within the LVAD in 12 percent.

• Most alarmingly, the incidence of stroke is 12 percent per LVAD patient-year (and as high as 30 percent in some reports) while it's about 4 percent in those without LVADs.

Just as I’ve seen patients whose lives were restored by the placement of an LVAD, I have seen others who spent months in intensive care, only to die directly or indirectly from these complications.

How can the overall positive results of LVADs square with these high complication rates?

Here's an analogy: You're given the chance to place $1,000 on an even-money bet where the odds are actually 2:1 in your favor. So for every three people who make the bet, two will win $1,000 each, but the third person will lose $1,000.

The group as a whole will have bet $3,000 and walk away with $4,000, which makes for a positive outcome for the group — but one of the three will come out $1,000 poorer.

Statistically, you’re likely to do better, but there’s a serious chance you’ll be made seriously worse.

It’s something like that with LVADs: Statistically, you’re likely to do better, but there’s a serious chance you’ll be made seriously worse.

Of course, technology improves with time. A clinical trial just published in May showed that a newer-model LVAD had significantly fewer complications. This is encouraging, but it will be important to see whether these outcomes hold true in practice — particularly because almost on the day that study was published, the manufacturer recalled the device to deal with technical problems.

So back to you, our heart-failure patient. What should you do?

This we know: You need to be able to make a well-informed decision. And, overall, this doesn’t seem to be happening the way it ought to be. A recent study looked at the effects of energetically educating both doctors and patients — including a video and pamphlet for patients — on the risks and benefits of LVADs. The percent of patients choosing the LVAD dropped from about 80 percent to about 54 percent.

An accompanying editorial in the journal JAMA Internal Medicine notes that this finding "raises the alarming possibility that many patients [...] are consenting to an LVAD without being fully aware of the risks and benefits, and may have chosen otherwise with more information."

That really is alarming.

Why Is This Happening?

Are doctors nefariously withholding information from their patients to sway them to opt for LVADs? The devices generate huge revenues both for the device industry and for the medical center, and it would be naive to argue that this has no possible influence. And many of the authors of papers in the medical literature on LVADs disclose financial relationships with device makers. They may be paid to speak at professional meetings, for example.

But financial incentives are ubiquitous in medicine — a surgeon, after all, is paid more to operate than not to operate; that's never deterred me from having surgery when it was recommended. And patient outcomes in advanced heart failure programs are under intense scrutiny, giving doctors a powerful incentive to try to avoid putting LVADs in patients who seem likely to suffer complications.

Most importantly, doctors have a commitment to doing what’s best for their patients. None of us is unmoved by the suffering caused by the complications of these devices, and I have never seen a colleague promote the placement of an LVAD without believing it was in the patient’s best interests.

But I also see another factor at play: the fervor for LVADs among many advanced heart failure specialists, despite their complications and costs. At national meetings and in the medical literature, I see attitudes that are almost messianic among practitioners, who look upon themselves as pioneering a new era in the treatment of heart failure.

They may well be right — but it’s harder to be objective when you're passionate.

So What Would I Do?

As for patients, advanced heart failure is a debilitating disease, and those afflicted may feel deeply despondent. It’s understandable that advanced heart failure specialists feel a need to do all they can to offer the patient a better quality of life, even with the high potential for bad outcomes. None of us want to say "I’m sorry, I have nothing to offer you."

It may also be tempting for patients to focus on the promise rather than the potential complications of a new device, especially after talking to one of the patients who feel a thousand times better. (They’re not likely to speak to one with a bad outcome.)

Ultimately, dealing with complex probabilities is uncomfortable for patients and doctors alike. Few of us find it easy to process information like, "Procedure X offers a 65 percent chance of a 50 percent improvement though also a 35 percent chance of an 80 percent worsening of the patient’s condition." And even that is a tremendous oversimplification.

You may ask me: "So what would you do in my position?" Because I've seen so many bad outcomes with LVADs, the downside risks would weigh heavily on my thinking. Progress in developing devices with fewer bad outcomes is likely, and it could change my perspective. But right now, I think I would opt for an LVAD only if I felt I had no other options.

True, I don’t have heart failure, and I might feel very differently if I couldn’t do the things I now take for granted. And, in any case, what I would do isn't necessarily what you should do.

What has to happen, I think, is for both doctors and patients to be open to the difficult discussions that need to take place, in which the potential benefits and risks are considered fully. That communication is hard, and the stakes high.

We physicians need to do a better job of explaining. And I urge you, the patient, to try as best you can to understand the risk you’re taking when you have an LVAD implanted. Ask, for example, to see the pamphlet and video used in the study I mentioned above. Talk to other providers — not necessarily cardiologists — who have cared for LVAD patients. Talk to patients — though, as I mentioned earlier, it’s unlikely you’ll have the chance to talk to those with the worst outcomes.

I don't have an easy answer. It's a gamble. That LVAD will probably help you, and you may be one of the majority of patients who say afterwards, "I feel a thousand times better." Or not. Just make sure you can accept the risks before you say, "Yes."

Matthew Movsesian, M.D., is a cardiologist and professor in the Departments of Internal Medicine (Cardiovascular Medicine) and Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Utah.