Advertisement

How A Boy’s Delivery Tests A 'Team Birth Project' Aimed At Reducing C-Sections

Resume

The tiny hand and forearm slipped out too early. Babies are not delivered shoulder first. Dr. Terri Marino, an obstetrician who specializes in high risk deliveries, tucked it back inside the boy's mother.

"He was trying to shake my hand and I was like, 'I’m not having this, put your hand back in there,' " Marino would say later, after all 5 pounds, 1 ounce of the baby lay wailing under a heating lamp.

This is the story of how little Bryce McDougall tested the best efforts of more than a dozen medical staff at South Shore Hospital in Weymouth and a new way to reduce Cesarean sections developed by experts at Dr. Atul Gawande's Ariadne Labs in Boston. It starts on the last day of August at about 9:30 in the morning, while Bryce is still squirming inside his mother's belly.

Melisa McDougall has just checked into South Shore after a routine ultrasound. She's into her 36th week, with twins. Melisa says her doctors warned that her placenta wouldn't hold out much longer. She's propped up in bed, blond hair pulled into a neat bun, makeup still fresh, ordering a sub, when her regular obstetrician arrives.

"How are you?" asks Dr. Ruth Levesque, who sweeps into the room. "You’re going to have some babies today! Are you excited?"

Levesque claps her hands, chats a bit, and reviews steps she’s discussed with the McDougalls many times. Melisa will be given Pitocin, a drug to induce labor. Levesque will break her water. The first twin expected out, Brady, is head down, positioned for a normal vaginal delivery.

"You’re catching the first one," Levesque says turning to Shaun McDougall, a tall, lanky man who can barely contain his excitement. "I’ll be gloved with you because I have a degree, and we’ll see what happens with Baby B."

Baby B is Bryce, the boy who will really be the focus of what’s called the Team Birth Project and one of its main goals, fewer Cesarean sections. Right now Bryce is horizontal, floating across the top of Melisa's uterus. Babies do not come out sideways. That’s one reason she may be headed for a C-section. There’s another, says Levesque: Melisa delivered a daughter, now 4, by Cesarean.

"She has a scar on her uterus," Levesque explains, "and there’s a risk of the uterus opening on that previous site. So there’s a risk of uterine rupture, very rare, but there’s always a possibility."

A possibility that may be greater for Melisa because she's 37 and having twins. But the McDougalls want vaginal deliveries for both boys.

"I just feel like it’s better for the kids, better for the babies," says Melisa.

The Team Birth Project

Avoiding C-sections is also better for many moms. With Cesareans, there's a longer recovery period, a greater risk of infection and an association with injury and death. And most are not medically necessary, says Dr. Neel Shah, who directs the Delivery Decisions Initiative at Ariadne Labs.

"We're fairly confident that when you look nationally the plurality — if not the majority — of C-sections are probably avoidable," says Shah.

Those avoidable C-sections are the focus of the Team Birth Project, designed by Shah with input from roughly 50 doctors, nurses, midwives, doulas, public health and consumer advocates who focus on childbirth.

In describing the project, Shah begins with an acknowledgement: Childbirth is complicated. You’ve got two patients — the mother and the baby — and an ad hoc, often shifting team that, at a minimum, includes the mom, a nurse and a doctor.

"So you’ve got three people who have to come together and become a very high-performing team, in a really short period of time, for one of the most important moments in a person’s life," Shah says.

And this team has to perform at its best during an unpredictable event: labor. Shah says doctors and nurses generally agree about when a mom is in active labor, when a mom can have a vaginal delivery and when she needs a C-section.

"And then there’s this huge gray zone," Shah says, "and actually, everything about the Team Birth Project is about solving for the gray."

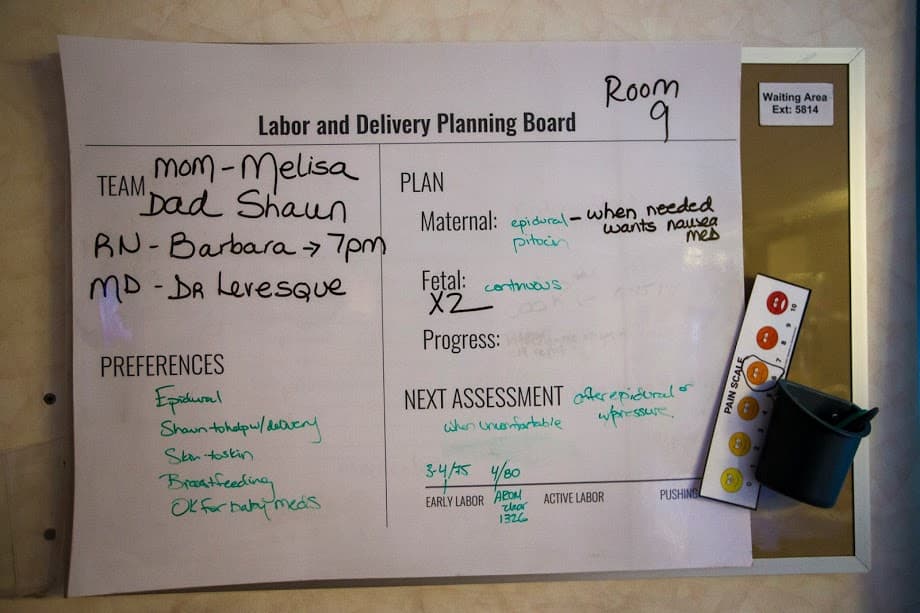

Project leaders are refining three tools to help doctors and nurses navigate the gray zones of childbirth. One helps them decide when to admit women preparing to deliver. There's a labor and delivery planning board in every room and a guide for the decision about when and how to deliver.

For the births of Bryce and Brady McDougall, the white erasable planning board got the most use.

Dr. Levesque and nurse Patty Newbitt added their names to the first of four categories listed on the board: the team. Melisa and Shaun McDougall are included as equal partners. The names of other family members or nurses may be added and erased as labor progresses. Shah's idea is that this team will meet or "huddle" regularly to discuss the evolving birth plan.

That plan is divided into three separate elements on the board: the mom, the baby and the labor, or how it is progressing. A mom with high blood pressure may need special attention, but that doesn’t mean she can’t have a normal labor and vaginal delivery.

Dr. Kim Dever, who chairs the OB/GYN department at South Shore, highlights a section called "Next Assessment."

"Because one of the things I often heard from patients is that they didn't know what was going to happen next," Dever says. "Now they know."

Back in the Melisa's room, Dr. Levesque has a green dry erase marker poised over an area labeled “Patient Preferences.” McDougall dictates steps that will guide her delivery: an epidural, husband Shaun helping with the first twin, Brady, and skin to skin contact immediately after birth.

"Perfect, yes, absolutely," says Levesque after each item.

Updating the board is sometimes an afterthought during McDougall's delivery, but Dr. Levesque says she likes using it.

"It forces us to stop and to think about everything with the patient," says Levesque. "It makes us verbalize our thought process, which I think is good."

Shaun McDougall walks across the room to get a closer look.

"Honestly, it seems like common sense," he says. "I would always think the nurses would have something like this but to have it out where mom and dad can see it, I think it’s pretty cool."

With Melisa McDougall's plan in place, everyone settles to wait. About four hours later, Melisa isn’t yet feeling contractions. Dr. Levesque breaks the water sack around Brady.

"Looks nice and clear," Levesque reports. "Hey bud, come on and hang out with us," she says to Brady, tickling his head. "So you’re going to keep leaking fluid until you leak babies. Whenever you start getting uncomfortable, we’ll get you an epidural at that point."

Levesque moves to the board with updates: Melisa is 4 centimeters dilated; broke her water at 13:26; the next assessment will be after epidural.

An epidural is Melisa's preference and her doctor's as well. In fact, they insisted Melisa agree to be numbed from the waist down if she wants to deliver Bryce vaginally. OBs may need to turn the baby, find a foot and pull Bryce out, causing pain most women would not tolerate.

One of those doctors peeks into the room and waves.

"Just came to say hi," says Dr. Terri Marino. She's a high-risk OB with more experience than most doctors in delivering babies positioned like Bryce. Marino has been seeing Melisa regularly, along with Dr. Levesque. Shaun McDougall asks if they’ll pose for a picture with his wife.

"Can we make funny faces?" asks Levesque.

"I want you to," says Shaun. "You guys are like her favorite people on the planet."

As the hours tick by, there's a nurse change, and Barbara Fatemi joins the McDougall team. She checks Melisa's pain level regularly to determine when she's ready for the epidural. Melisa says she isn't feeling much, but she has a high tolerance for pain. Shaun tells Fatemi he sees the strain on his wife’s face. Fatemi acts on Shaun’s assessment, something he later says reinforces his feeling that they’re a team.

After the epidural is in, but before the drugs start flowing, Melisa gets up to go to the bathroom. She returns looking scared, color draining from her face. Fatemi calls Dr. Levesque. While in the bathroom, Melisa felt the urge to push.

"I was not expecting that, so much pressure," says Melisa. "I mean, I didn’t feel anything until I went to the bathroom."

"You’re really shaking, are you OK?" asks Shaun. Melisa nods.

Levesque arrives for the promised "next assessment." Melisa is 10 centimeters dilated and ready to deliver. But she must hold on until nurses can get her into an operating room. She’ll deliver both babies there, in case Bryce doesn’t shift and she needs a last minute Cesarean.

"I’ll see you in a few minutes, no pushing without me, OK?" Levesque says over her shoulder as she heads to the OR to prep.

"I'll try," says Melisa, weakly. In a minute, nurses are rolling her down the hall, following Levesque.

Almost five years ago, two women wheeled into South Shore operating rooms during childbirth died. Both had C-sections. State investigators found no evidence of substandard care. But Dr. Dever says the hospital scrutinized everything.

"When you have something like that happen that expedites your efforts," Dever pauses, "exponentially."

Now Dever says she sees an opportunity, through the Team Birth Project, to model changes that could help women far and wide.

"I would love women everywhere to be able to come in and have a safe birth and healthy baby," she says. "If someone said 'why are you doing this?' That’s why I’m doing it."

Dever is about to see her pilot program, the Team Birth Project, pushed to new limits by little Bryce McDougall. First though, Melisa must push out Bryce’s brother, Brady. Even he, the expected easier birth, is more difficult than anticipated.

Bent nearly in half, her face beet red, Melisa strains for five pushes. She throws up and get back to it. And suddenly, there he is.

"Oh my goodness Brady, oh Brady," wails Shaun. He follows a nurse holding his son to a warmer.

Marino takes Shaun's place next to Levesque who has reached inside Melisa. Her mission is to grab Bryce’s feet and guide him out. But everything feels like fingers, not toes.

"That’s a hand," she murmurs, "that’s a hand too."

Marino rolls an ultrasound across Melisa’s belly, hoping the scan will show a foot. But Bryce’s feet are out of sight and out of reach.

"Feels like a hand," Levesque says, her forehead wrinkling. "Yeah, hand, all I get is hands."

Marino, who has more experience with transverse babies, and this procedure, known as a breech extraction, asks to try. She reaches into Melisa’s uterus while Levesque moves to Melisa’s right side and uses her forearm to shift Bryce and push him down. Dever, the head of OB, has come in and takes over the ultrasound. At least six doctors and nurses encircle Melisa, whose face is taut. Shaun frowns.

"Babe, you OK?" he asks.

Melisa nods. Bryce’s heart rate is steady. But there’s still no sign of a foot. His hands are so close one slips out. Dr. Marino nudges it back in.

"Open the table," says Marino, her voice strained.

It’s open, it's ready, her colleagues say, referring to an array of sterile surgical instruments Marino may turn to any minute now to begin a Cesarean.

Then Dr. Marino asks to stop recording for a moment.

For 36 seconds, this room with more than a dozen adults grows oddly quiet, watching Marino twist her arm this way and that, determined to find Bryce’s feet. Levesque leans hard into Melisa’s belly. Shaun bites his lip. Then Marino yanks at something and her gloved, bloodied hand emerges, clenching two teensy legs.

"Oh babe here he comes, here he comes, woo!" squeals Shaun.

Shaun is overcome with emotion again. Melisa manages an exhausted giggle. Bryce keeps everyone waiting a few more seconds and then howls.

Levesque starts to stitch a small tear for Melisa. Marino comes around to congratulate her.

"I had to win against him," Marino tells Melisa.

"He was fighting you, huh?" Melisa laughs.

"He was trying to shake my hand and I was like, ' I’m not having this, put your hand back in there,' " Marino says.

"I think I found at least five hands," adds Levesque.

Outside the OR, Levesque and Marino look relieved and elated. Both agree that most doctors would have delivered Bryce by C-section. But at South Shore, the McDougalls had a hospital that has challenged itself to perform fewer C-sections and a doctor with experience in these unusual deliveries, one who knew the parents’ preference.

"They specifically wanted to have vaginal delivery of both babies," Marino says, and that was on her mind during those difficult moments.

Bryce was fine, says Marino, so the deciding factor was that Shaun and Melisa did not panic.

"They did not flinch, they were like, keep going," Marino recalls. "Sometimes the patient will say stop and then you have to stop."

Shaun says he came close in that last minute before Bryce was born.

"That part with the arm, it was pretty aggressive," Shaun says.

But Shaun says in that moment, the feeling that he and Melissa were part of the team made a difference.

"It made us more comfortable," Shaun says, which translated to trust. "We trusted the decisions they were making."

Melisa says she’s grateful for the vaginal delivery.

"I did not want to have a natural birth and a C-section, that would be a brutal recovery," she says.

Instead, 30 minutes after Marino pulled Bryce out of her, Melisa is nursing Brady and FaceTiming with family members.

'Next Assessment' For The Team Birth Project

South Shore began using the Team Birth approach in April. Three other hospitals are also pilot sites: Saint Francis in Tulsa, Oklahoma; Evergreen in Kirkland, Washington; and Overlake in Redmond, Washington. The test period runs for two years. In the first four months at South Shore, the hospital’s primary, low-risk C-section rate dropped from 31 percent to 27 percent — about four fewer C-sections each month.

Experts who contributed to the development of the Team Birth Project are anxious to see if other hospitals can lower C-section rates and keep them down.

"Once you get past the early adopters, how do you demonstrate the benefits for others that aren't willing to change?" asks Gene Declercq, a professor of community health sciences at Boston University School of Public Health.

Declercq notes that a few insurers are beginning to force that question, refusing to include hospitals with high C-section rates and other unnecessary if not harmful care.

Declercq says the project's focus on communication in the labor and delivery room makes sense because many physicians decide when to perform a Cesarean based on habit or the culture of their hospital.

"If you can impact that decision-making process, you can perhaps change the culture that might lead to unnecessary Cesareans," says Declercq.

There's no optimal rate for Cesareans. The latest data from the Centers for Disease Control puts the U.S. average at 31.9 percent. Some health experts say hospitals that do more than 19 percent need to look at why.

Another contributor, Carol Sakala, the project's standard practices could rein in the hospitals that perform too many C-sections. But she worries about the focus on hospitals.

"There are so many things a woman can do to reduce their likelihood of a C-section if they have an awareness before they get to a hospital," says Sakala. She mentions using midwives and doulas and registering with a birth center.

Sakala has some concerns about the project's emphasis on women as equal contributing members to their delivery team. She says adding stress or anxiety to the experience can trigger hormones that slow labor.

"Women need to stop being thinkers, stop texting their friends and ideally be given a safe quiet space to relax and allow the hormones to keep the stress at bay," Sakala says.

Team Birth Project leaders say they expect to make adjustments using feedback from experts and more importantly from nurses, doctors and midwives and moms who use the approach during deliveries.

This segment aired on September 24, 2018.