Advertisement

In Boston Courtroom, Cancer Research Titans Clash Over Patents Likely Worth Billions

It's not the kind of trial that draws TV cameras outside the courthouse, but make no mistake: This is a legal clash between giants.

Giants of science, that is. The spoils of this battle are patents related to immunotherapy, the revolutionary new type of cancer treatment that unleashes the body's own immune system. And they could be worth billions.

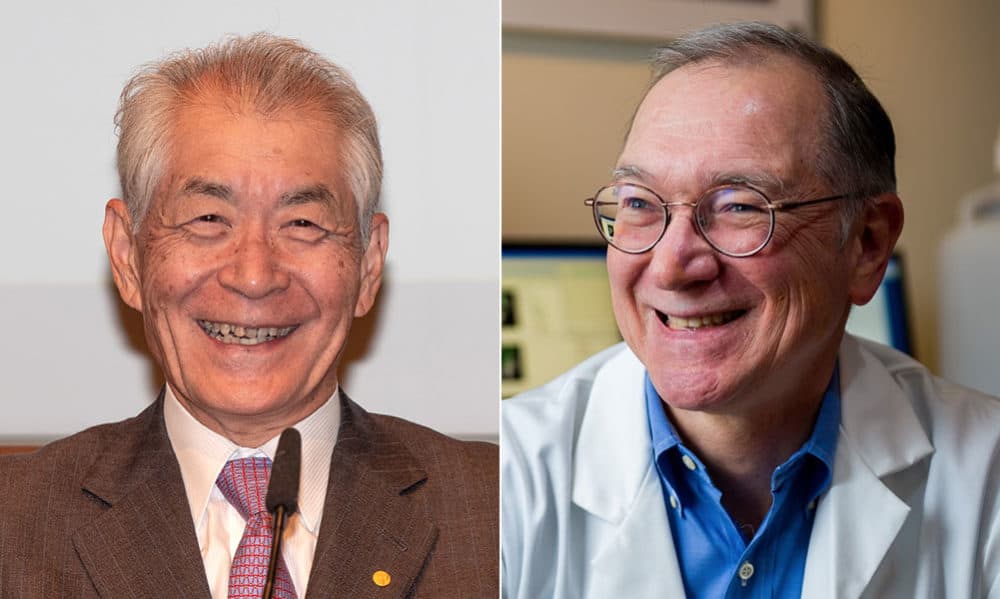

On one side of the high-stakes drama playing out in federal court in Boston over the last two weeks is Dr. Tasuku Honjo from Kyoto University. At age 77, he just shared in a Nobel Prize for his work on immunotherapy.

In his Nobel lecture in December, Honjo said he hopes that immunotherapy will eventually transform cancer treatment the way antibiotics have transformed treatment for infections.

"Cancer may not completely disappear, but be controlled by immunotherapy," he said. "Cancer may become one of the chronic diseases. If you still have a tumor but no growth, that's OK."

On the other side is Dana-Farber Cancer Institute researcher Dr. Gordon Freeman, a Harvard Medical School professor and immunotherapy pioneer who's won major prizes himself, though not the Nobel.

In a recent interview unconnected to the trial, he described the current excitement around immunotherapy: "Everyone wants to work in the area because it's so important," he said. "Really the best and the brightest scientists, and the most innovative and cutting-edge technologies, are being applied to the problems of immunotherapy."

That's now. But the focus of the federal trial in Boston is nearly 20 years ago, when some of the seminal science that led to immunotherapy was done.

At the center of the case are a half-dozen key patents that list Honjo and Japanese colleagues as inventors, but not Freeman and another American colleague.

Advertisement

Dana-Farber, the plaintiff in the suit, is arguing that the Americans should be included on those patents, that they made significant contributions.

Dr. Honjo's side includes the pharma giant Bristol-Myers Squibb, which now holds the licenses that control the use of those patents. Honjo himself took the stand for many hours of confident and sometimes slightly testy testimony. He argued that no, he got no significant help from his American colleagues.

One thing is sure: The stakes are high.

"The patents that are currently issued to Professor Honjo are probably worth billions of dollars," said professor Jake Sherkow of New York Law School, an expert on patent disputes in the life sciences.

The patents at issue relate to multiple immunotherapy drugs that are each selling for a couple of billion dollars a year, he said.

"We've got Keytruda, we've got Opdivo, we've got Libtayo, we've got Tecentriq, we've got Bavencio, we've got Imfinzi — all of these drugs are, if not blockbuster drugs, at least pretty close to it," he said. "So that's what this dispute is all about."

Except this case is not only about money.

"It goes directly towards issue of scientific credit, honesty and reliability," Sherkow said. "So those things combined, if you add money to the mix, it makes a particularly potent poison."

The lawsuit is so scientifically complex that presiding Chief Judge Patti Saris has jokingly complained that she's being buried under loose leaf binders of exhibits. They include handwritten pages from lab notebooks, science journal papers, slide presentations, tutorials on immunology and emails.

The story begins back in the early '90s, when Dr. Honjo discovered a molecule called PD-1 on the surface of immune cells called T cells. It seemed important, but what it did, and how it worked wasn't clear.

In late 1999, Honjo started working with Freeman at Dana-Farber and another scientist at a Cambridge biotech company on a related molecule the two Americans had pinpointed that's now called PDL-1.

It turned out, PD-1 and PDL-1 work together in a system now called the PD-1 pathway. Freeman explained with a metaphor: "If you think of PDL-1 as your foot pushing down on the brake pedal, PD-1 is the brake pedal."

Cancer can take advantage of those brakes to protect itself against immune attack. To outwit it, immunotherapy can use antibodies that lift your foot, so to speak, so it can't press the brake that would protect the tumor from attack.

Immunotherapy drugs that use this PD-1 pathway are already prescribed against many types of cancers — including lung cancer — and they're being tested in many combinations as well.

So who deserves credit on the patents?

Testimony at the trial has focused heavily on the exchange of biological materials and unpublished data between the American and the Japanese researchers in 1999 and 2000.

The legal crux of the case is how significant the Americans' contributions were to the work that led to the patents. One lawyer compared the case to deciding who gets credit for completing a jigsaw puzzle that includes many pieces put in by multiple players.

It's the sort of dispute we can expect to see more of.

"Modern science involves collaboration across laboratories, across scientific disciplines, and many involve collaboration with industry as well," said Dr. Jeffrey Flier, the former dean of Harvard Medical School, who researches and writes about credit in science.

"So the complexity of the scientific papers that come out — and of the patents and the credit that results — is far, far greater than it used to be," he said.

And the financial stakes are higher, said Sherkow from New York Law School.

"It used to be a rare event to have an invention and a small set of patents that could command billions of dollars," he said. "And today, it's just another day in the newspaper."

Closing arguments in the Dana-Farber suit are expected next Friday, Feb. 22, and it's likely to be months before Chief Judge Saris issues a decision.

Given the amount of money at stake, whatever the decision is, it's likely to be appealed.

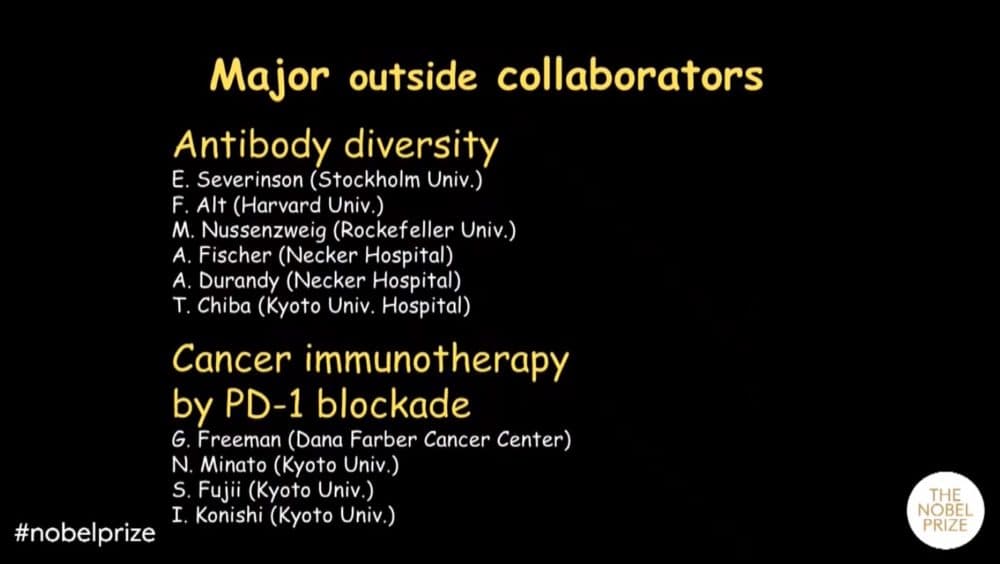

A legal battle royale like this pits scientists against each other, but at the very end of Dr. Honjo's Nobel Prize lecture, there was what looked like perhaps a brief moment of conciliation.

He was thanking all his collaborators, and said, "Well, I think it's too much, because there are more people than I could list — I lived so long, so I owe so many people."

On his slide, in the list of collaborators on immunotherapy, the first name is "G. Freeman," from Dana-Farber.

This segment aired on February 19, 2019.