Advertisement

Electronic Health Record 'Gag Clauses' May Soon Come Off

Resume

Dr. David Bates sits at an office computer at Brigham and Women's Hospital and regretfully declines to demonstrate his expertise.

Bates, the hospital's chief of general internal medicine, is also a leading researcher on electronic health records and how they affect patient safety. For example, an ideal system prevents a doctor from prescribing the wrong medication; a less-than-ideal system might let the mistake through, or even make it more likely.

I've asked him to show me an example of a potential safety issue on the electronic medical record in front of him, a sample with no real patient data in it.

"I'd like to, but I can't," he replies politely. "I would be potentially legally liable if I did so." And that would be true at most hospitals in the country, he says.

It's not just the back-end software code Bates can't share, he explains — it's the screens that all hospital staffers using the system can see. Without special permission, he says, he's not free to share screenshots or videos of specific issues that could lead a doctor to make a mistake — even in the medical journals where doctors often warn each other of potential risks to patients.

"We've had instances in which we thought that someone was harmed because of the way the electronic record was set up," he says. "But legally, we're not allowed to share those issues today." And that's not right, Bates says: "If you do have an [information technology]-related issue that causes a safety problem, I think, as do other leading safety experts, that we should be able to share it with everyone."

The types of restrictions Bates is highlighting are widely referred to as "gag clauses" in the contracts that hospitals and medical practices sign with the vendors of electronic health records.

As the federal government proposes new rules for medical records, there's reason to believe that those gags may soon come off.

Dr. Raj Ratwani, director of the MedStar Health National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare in Washington, D.C., says freer speech is needed to help make electronic records safer and more user-friendly.

"Electronic health records are a positive thing; the majority of clinicians would never want to go back to paper," he says. "Having said that, there are some unintended consequences to the technology, and these gag clauses in particular have prevented us from being able to really quantify that impact."

The Doctors Company, a big medical malpractice insurance company, estimates that between 1 and 2 percent of their malpractice cases involve some problem with electronic health records, according to vice president Darrell Ranum.

"Now, we think that that's probably the tip of the iceberg," he says, but it's hard to say how big the problem really is. "We really don't know how many patients out there are being harmed because sometimes those issues don't come to light and don't make it to the level of a malpractice claim or lawsuit."

What Dr. Ratwani at MedStar can say is that despite the gag clauses, he and others have documented some risks. For example, when the electronic chart makes it easy to confuse the box for recording a child's height with the box for weight, or to confuse pounds with kilograms.

"Then we have an inaccurate weight for the child, and because of some of these issues, we've actually seen children being harmed," he says. "Because they receive an overdose — or an underdose, but typically it's an overdose — of the medication that then leads to harm. And there's several more examples like that, unfortunately."

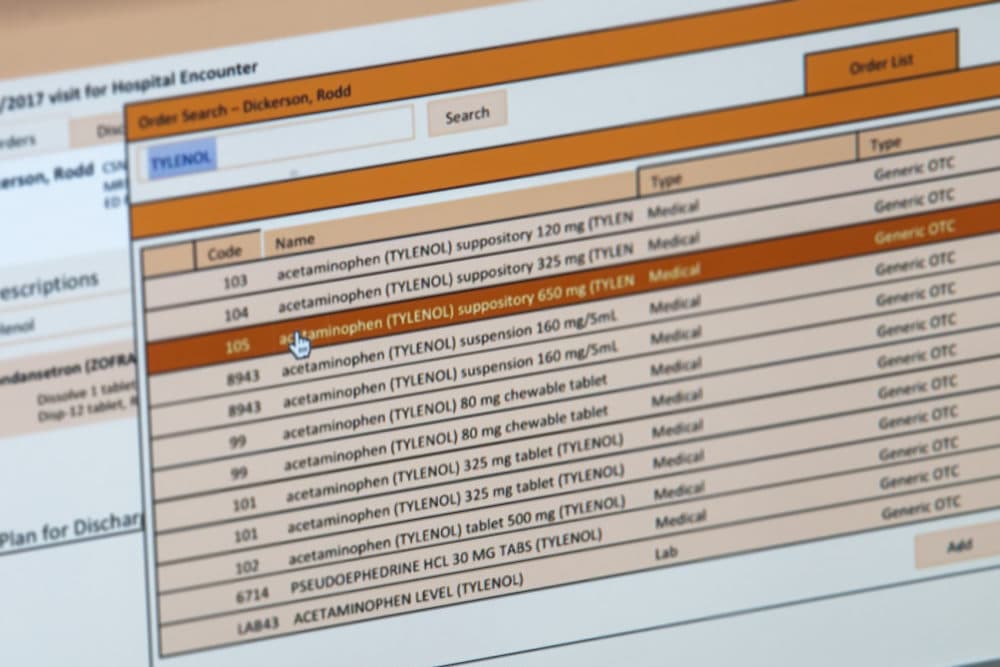

Say a doctor wants to order Tylenol for an adult male patient at a very common dosage — 500 milligrams. The screen may show 86 different possible Tylenol orders, including some for children and women. That kind of information overload is not just tiring for doctors, Ratwani says — it can lead to wrong medications being selected. (Examples here.)

Dr. John Levinson, a Harvard cardiologist, contrasts those busy screens with the in-flight dashboard he uses as a small-plane pilot: It tells him exactly what he needs to know and no more.

"And the electronic health records that I've used are absolutely atrocious at that," he says. "They show you a vomit of unnecessary data which gets in the way."

Levinson is no Luddite. He's an information technology maven who wrote an electronic health record himself back in the late '80s.

"I think these electronic health records are good things," he says. "But you know, patient safety is first, second and third. It has to be."

So when Levinson recently got word from Ratwani that he was asking for signatures on a letter to Congress urging more action to ensure the safety of electronic health records, "I sent it to probably 800 of my closest friends," he says. "And pretty much everybody has signed it."

The letter comes at a pivot point for electronic health records: The federal government's Office of the National Coordinator of Health Information Technology is proposing a new set of rules, based on changes required by Congress in a big 2016 law. Among 700-plus pages of other things, the proposal would ban "gag clauses."

"The proposed rule says that there is a growing recognition that prohibiting or restricting communication about health IT software doesn't promote safety," says Dr. Andrew Gettinger, the office's chief clinical officer.

"We're seeking public comment to see if there are a lot of gag clauses in use today," he says, as well as on many other issues, from now until early May.

Though there's no official count of how common gag clauses are, a Politico investigation in 2015 used public records requests to turn up a dozen, and a major Fortune/Kaiser Health News investigation this month explores the issue as well.

Electronic health records companies are reviewing the proposed rule. Meghan Roh, spokeswoman for the records company Epic, says in an email that Epic contracts do not have clauses that prohibit criticism, and that information technology companies consider their screens and code confidential — if they didn't, their screens could be reverse-engineered by competitors.

She says last year, Epic approved 96 percent of customer requests to share screenshots of its software.

But Dr. Ratwani from MedStar got turned down, he says, when he asked Epic a couple of years ago for permission to share videos of doctors interacting with its software for a research project to advance health-record safety and usability.

"As Health IT safety community members, we were really disappointed," he says.

His team instead uses videos that simulate challenges with Epic, along with videos of medical staffers using actual records systems from another company, Cerner. They share examples on a new website — EHRSeeWhatWeMean.org.

Visitors to the site "can finally see the kinds of usability and safety challenges that are impacting our clinicians and ultimately are impacting our patients," Ratwani says.

He is calling for a central reporting system for safety issues with electronic health records, much like the systems used to report problems with drugs or medical devices.

Back at Brigham and Women's, which uses an Epic system, Dr. Bates points out that many more people have died from flaws in medical software than in aviation software of the type thought to be involved in the recent Boeing plane crashes.

He does think health care is safer with electronic health records, he says, "but it's just not nearly as safe as it could or should be if we were a little more effective at fixing these flaws."

This segment aired on March 29, 2019.