Advertisement

Shortage Of Life-Saving Infusion Strains Hospitals And Leaves Patients In Limbo

For the last eight years, Leslie MacGregor from Newton, Massachusetts, has been getting intravenous infusions every month. The treatment is called immunoglobulin, and it bolsters her defective immune system with concentrated, infection-fighting antibodies from healthy donors.

Without it, she would get serious infections of her lungs or skin, bad enough to land in the hospital. She would also suffer autoimmune attacks that cause agonizing nerve pain. When they flare up, she says, "it makes me feel like my feet and legs are being dipped in boiling oil."

MacGregor's latest infusion was scheduled for the end of June at Massachusetts General Hospital. Five days before, her doctor called and told her that she would only be able to get half her usual dose, and that her next six months of scheduled infusions were all canceled.

Instead, she will have to try to give herself frequent, painful immunoglobulin injections at home, with added risks, she says.

"Mass. General has been a wonderful and expert, dependable, safe place for me to go with multiple chronic severe medical conditions for 15 years, and I trust them to do a good job," MacGregor says. "This episode doesn't fit with their profile."

Intravenous immunoglobulin is used to treat many medical conditions, from chronic to acutely life-threatening, and its supply recently shifted abruptly and indefinitely, says Dr. Paul Biddinger, the chief of emergency preparedness at Mass. General.

Signs of a crunch had been building for months, "but really, it's within the last couple of weeks that it's become a critical shortage across the whole country," he says.

"We don't really know why the shortage exists, which is incredibly frustrating," he says, "but it really affects a large number of patients, from neonatal patients to cancer patients, to immunology patients, transplant patients."

The hospital is taking the immunoglobulin shortage seriously — so seriously that late last month it activated its Incident Command System, which is normally used for disasters like the Boston Marathon bombing or extreme weather, to address the danger that the hospital would run out.

Advertisement

From A Trickle To A Stream

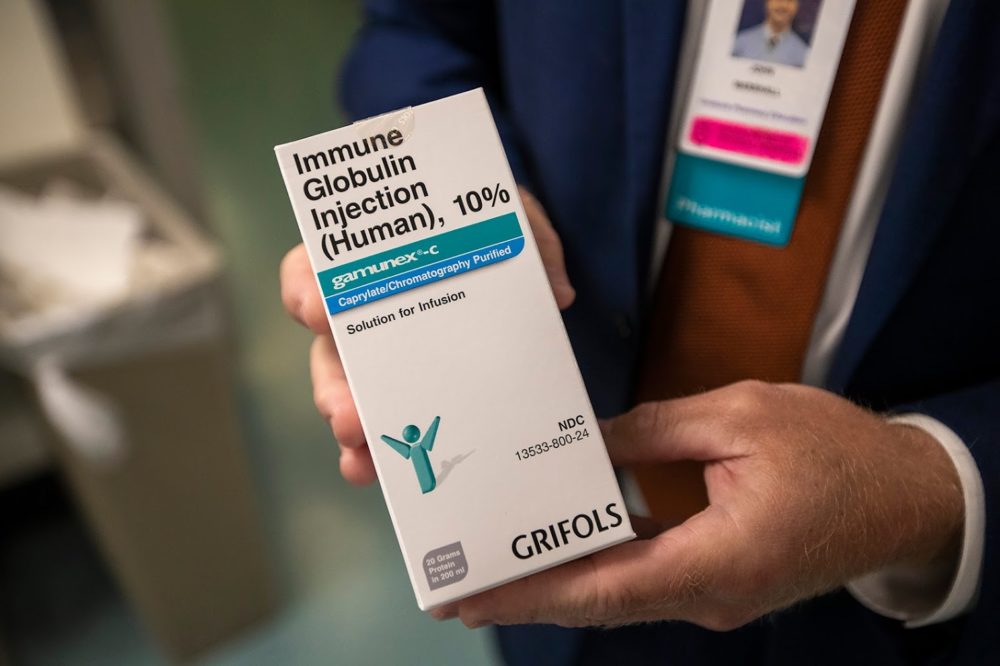

In the hospital's busy pharmacy, Director of Clinical Pharmacy Services John Marshall estimates that a 22-day supply is now on hand — "remarkably good considering we were at a much shorter stock level even a few days ago," he says.

"We got some in, and we've been able to work with clinicians across service lines to conserve, to minimize waste, and to identify other therapeutic alternatives for patients as clinically appropriate," he says.

The hospital also divides patients into categories based on level of need, including what Marshall calls a "break-the-glass" cache for the most dire medical crises.

It is harrowing when the supply drops to just two or three days, he admits. And while he praises the hospital's teamwork, he also acknowledges that it's "making the best of a very difficult situation."

Such difficult situations have been cropping up sporadically around the country for months, says John Boyle, president of the Immune Deficiency Foundation, a national nonprofit.

But lately, a trickle has turned into a stream of reports that clusters of patients are being told there's not enough immunoglobulin on hand for them to come in for their usual infusions, he says.

"It's that volume of people that are all of a sudden being told things have changed," Boyle says. "And in a lot of cases, the hospital or whoever is administering it is not really giving them a plan B. It's more, 'Stay tuned and we'll do what we can when we can.' "

The longer someone who needs immunoglobulin goes without it, the greater the danger. "It's frightening, because our lives depend on it," says Boyle, who has a genetic immune deficiency. "Without immunoglobulin, we get sick. We get sicker and sicker. And some of our conditions, mine included, mean that if I don't get immunoglobulin, you know, I'm not going to be around."

Boyle sees rising demand for immunoglobulin as the main factor in the shortage: It's being used for more and more conditions — some with official approval and plenty of evidence, some off-label and with little evidence.

The manufacturers also blame rising demand, says Michael Ganio, spokesman for the American Society of Health System Pharmacists, which has been tracking the shortage.

But that's a long trend, not a sudden spike. So why a sharp shortage?

"We don't exactly know," he says, "and that's part of the problem with shortages in the United States: We don't have complete transparent information."

Two manufacturing sites have had recent quality issues, Ganio says.

And two new immunoglobulin products recently got FDA approval, he adds. "That means that there's likely a supply building up somewhere for market release, and that's taking away from some of the supply."

But that's speculation to some degree, Ganio notes: "Right now we don't have complete clear information on why all of these products are on back-order."

Takeda Pharmaceutical, one of several large manufacturers of intravenous immunoglobulin, says it recognizes the seriousness of the shortage and is working to try to keep its products available.

And longer term, it's trying to collect more plasma — immunoglobulin is made from donated human blood plasma — and expand its manufacturing capacity, including by investing more than $1 billion in a new plant in Georgia that's up and running.

"Over the past 15 years we have seen demand for immunoglobulins steadily increase," writes Kasandra Carr, spokeswoman for Takeda’s U.S. Immunology Business Unit, which is based in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

"This increase in demand, together with the time it takes to produce plasma-based products has led to very tight supply and, in some cases, supply interruptions for certain products," she says. "Addressing the needs of the people who rely on our therapies is our top priority."

No Quick Fix

One thing is clear: The shortage is not expected to end soon. It takes months to make immunoglobulin treatments from plasma. Mass. General has been told the shortage could last a year, Biddinger says.

Hospitals are used to dealing with dozens of drug shortages, he says, but this one is looking unusually long — and hard, because some uses of IV immunoglobulin lack substitutes or workarounds.

"It means that even for patients for whom we've either tried to decrease the dose or extend the interval between the doses, they still are going to be at risk for a long period of time," he says. "That's hard for us to deal with. I think it's really frustrating for those of us in medicine that we realize how tenuous our supply chain is.

"There is no safety net," he says. "To be in the United States health care system and to have therapies that we know work, and medicines we know are effective, and to run out really should be unacceptable."

On The Case

The Massachusetts Health & Hospital Association has received anecdotal accounts that the national shortage is hitting hospitals throughout the state, says spokesperson Catherine Bromberg.

"While each hospital’s situation is unique, some responses include conserving supplies for patients who are critically ill, cancelling certain patient visits, and working to identify alternative treatment options as appropriate," she emails.

The Massachusetts Department of Public Health says it is closely monitoring the shortage "to anticipate its potential impact on patient care in Massachusetts," and providing guidance to hospitals.

Next week, a group of Greater Boston hospitals are planning to confer to discuss possible next steps and collective actions to address the shortage.

What Are Patients To Do?

Boyle at the Immune Deficiency Foundation says the nonprofit will try to help patients as it can; last week he issued a plea for responsible immunoglobulin stewardship. An estimated 250,000 Americans have the rare genetic disorders known as primary immune deficiency diseases, he says, and many of them need the infusions.

"There's no one central authority that can sweep their hand and say, 'This is a matter of national security,' " he says. And there's no central list of where immunoglobulin is available.

It's helpful when large institutions like Mass. General speak up to say "these are not just a few isolated cases," he says. And patients will need to advocate for themselves: "You need to be a squeaky, squeaky wheel."

In Bangor, Maine, patient advocate Dawn DeBois has written about the shortage and her concern that patients aren't able to get the immunoglobulin they need.

Because her immunoglobulin treatment was canceled recently, the symptoms of her autoimmune disease escalated rapidly, DeBois says, "to the point that I was having difficulty getting up one step in my house. I was having difficulty getting up from my chair, and breathing at night."

She was going downhill fast, having a hard time even conversing. Fortunately, she did get her intravenous immunoglobulin, or IVIG, at the beginning of July and improved.

But, she says, "my heart goes out to those patients who still have not had their treatments, in the facilities that are not getting their IVIG. I just don't even know how those patients are handling it right now."

This segment aired on July 22, 2019.