Advertisement

Families Fought For A New Drug's Approval. Now They Fear Insurers Will Drop It

In early childhood, the signs of Duchenne muscular dystrophy include difficulty running, climbing stairs and standing up. Children with this rare genetic disorder can’t produce enough dystrophin, a protein that helps their bodies repair and build muscle. As they get older, they lose the ability to climb stairs at all. Then they lose the ability to walk, use their arms and, eventually, their lungs and heart.

The condition is fatal. Most people with Duchenne, which primarily affects boys, die in their 20s.

But a drug that came on the market about three years ago, called eteplirsen, gave patients and their families hope. Eteplirsen, developed by Cambridge-based Sarepta Therapeutics, is supposed to slow the progression of Duchenne by partially restoring the body’s ability to produce dystrophin, and families fought for its approval by the FDA.

Now, a report from the nonprofit Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, or ICER, a drug price watchdog organization, says at $1 million per year, the drug isn’t cost-effective.

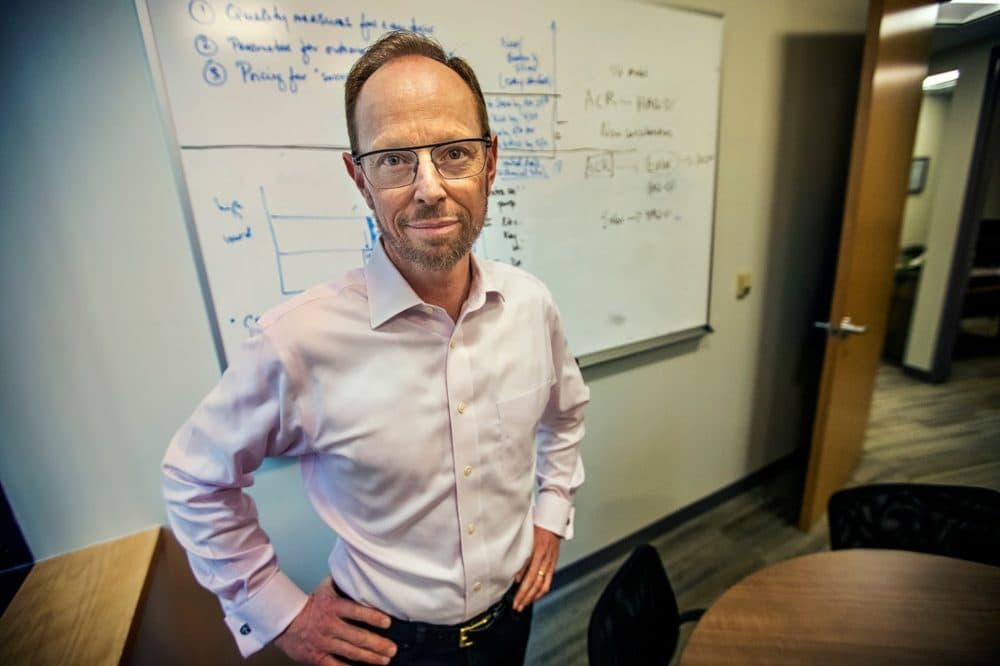

“The drug would have to be miraculously effective and curing patients and extending their life by 40 years or more to even come close to being cost-effective,” says Dr. Steven Pearson, ICER’s president. And, he says, the evidence does not suggest eteplirsen is curing patients.

ICER's conclusion has patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy and their families worried, and it led to a tense meeting with ICER's review panel this week in Cambridge.

Their concern is that if a treatment is seen as having both little evidence that it works and a high cost, health insurers may choose not to cover it. “It puts doubts in the insurers' minds as to whether it’s worth it to keep these treatments,” says Fleur Chandler, a health economist with patient organization Duchenne UK and the mother of a 13-year-old boy with Duchenne. “That then makes an impact in whether these drugs are available,” she says.

ICER’s reports typically provide a recommendation for what it calculates would be a fair price for the drugs it evaluates. The recommendation is based on a combination of factors, including the available medical evidence on how well the drug works. ICER says its reports are not meant to get between patients and their doctors.

Advertisement

“We’re trying to take a stand on behalf of patients in the health system, and we need a better platform to support innovation that doesn’t bankrupt families and the health care system,” Pearson says.

In the past, ICER’s reports have argued that certain drugs were unfairly priced and helped put enough pressure on drug companies that they slashed prices. But in the case of eteplirsen, there is very little good evidence available, Pearson says. So, ICER couldn’t make a price recommendation.

Pearson says that when the drug was in development, the company measured how far children could walk after six months on the treatment to measure the drug’s effectiveness. But Pearson and patient advocates say that test doesn’t capture how much patients are actually improving.

“When companies don’t do good research it makes it impossible for people to actually assess [the drug’s] effectiveness, and we don’t have a drop of additional evidence that helps us judge these drugs today,” Pearson says. “That’s why there’s so much stress and conflict in addition to the pricing.”

Those in the Duchenne patient community argue that this lack of evidence should make ICER's findings invalid.

“It’s like building a house on a rickety foundation,” says Mindy Leffler, the mother of a 16-year-old with Duchenne. She’s also the president of Casimir, an organization pushing for better research methods on the disease. “If you’re building your pricing model on top of unreliable sources of evidence, then you can’t really have any faith in your pricing model,” she says.

Higher quality research is needed before anyone can make judgments on whether eteplirsen is medically effective or cost-effective, says Fleur Chandler from Duchenne UK. “If you cannot come up with an economically justifiable price, it probably means the model is not appropriate,” she said at the meeting with ICER on Thursday.

And ICER should have considered benefits the drug might provide that were never measured in studies, says Christine McSherry, another mother, whose son was part of the eteplirsen drug trials. McSherry also spoke at the meeting, asking: “Why don’t we take into consideration quality of life and independence? We need to listen to the patients to understand what’s happening and understand the quality of life measures to them.”

McSherry says that her son's condition improved on eteplirsen. "The snore had gone down, and his breathing was steady, and, for the first time, I didn't hear any apnea at all," she recalled at the meeting. "He's doing better in school, communicating more."

None of those quality of life changes were captured in the studies evaluating eteplirsen, she says.

ICER is listening to concerns like McSherry's, and Pearson says feedback from the Duchenne patient community is being incorporated into the organization's work.

“They came with a tremendous understanding of the science and the evidence that needs to be generated with a broader view of the experience of families with this condition,” he says. “One of our recommendations will be for patients to be part of this process. Drug companies should have worked with patients and clinical researchers to develop better research.”

That, he hopes, will lead to the information ICER needs to determine a fair price for eteplirsen and other drugs for rare diseases. But in the meantime, ICER's review board upheld the finding that eteplirsen, whatever its benefits, is not worth its current $1 million annual price tag.