Advertisement

You Might Not Really Be As Into All This Negative News As You Seem

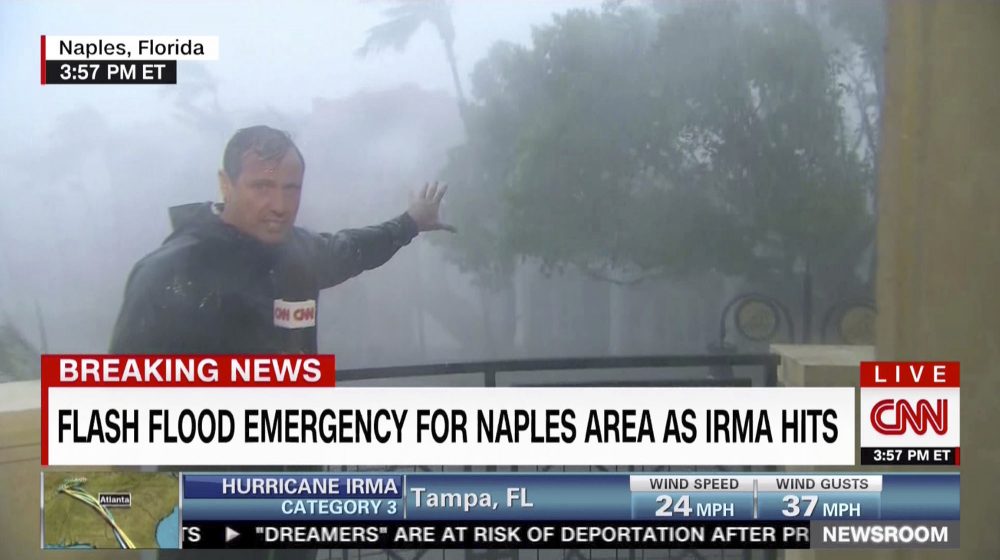

As you trawl through the news, you likely find yourself drawn willy-nilly to the plentiful negative stories: The latest mass shooting, hurricane, disease outbreak.

That's the phenomenon described by the old journalism phrase "If it bleeds, it leads." In academia, it's studied as "negativity bias" — including in a new paper out this week looking at the proclivity for negativity across 17 different countries.

What you may not notice as you watch videos of trees blowing down or perps walking is that your body is subtly reacting, expressing your interest — or lack thereof — via physiological measures of arousal. These measures include skin conductance — are you slightly excited and so sweating a bit more? — and heart rate — is it a bit faster because you're juiced by something? A bit slower because you're so focused?

The new study measured those responses in more than 1,000 news video watchers across six continents, in what University of Michigan Professor Stuart Soroka says is apparently "the single largest body of data on psychophysiological responses to content."

His research team expected to find that the bias toward negativity holds across humanity. On average, it did.

That's not surprising, Soroka says, given how we likely evolved: "We need to avoid negative things more than we need to approach positive things," he says. "If your friend gets eaten when you're at a bush that has berries, you need to be the animal that never goes back."

But the research also turned up some surprises. Negativity bias didn't vary broadly depending on the national context. Instead, "what we found was that there's huge individual-level variation," Soroka says. People vary greatly from one another in how much their bodies show a preference for negative news, he says, but those differences are "within countries, not so much across them."

Another surprise: In many countries, up to 40% of the sample showed either no negativity bias or a bias toward the positive.

Those findings lead to a provocative suggestion for media decision-makers: "Maybe there's a space for less negative news," Soroka says, "because there appear to be large proportions — not majorities but large minorities of respondents in any one of the countries we studied — who are more activated by more positive information than by negative information."

People may be drawn differently to news depending on time or circumstance. In other work, Soroka argues that it may not be negativity per se that grabs people, but rather whether something is "outlying," whether it contrasts with the environment and thus commands more attention.

"If your regular daily life is marginally positive — like you get up in the morning and water comes out of the tap, and you get to work on time," then "the more outlying information would be the negative stuff," Soroka says. "But you can imagine an environment in which things are sufficiently negative that actually it's the positive news that becomes outlying."

That's been shown with news about the economy, he says. In the midst of the last recession, for example, news about a slightly less steep rise in joblessness — a slowdown in the unemployment trend — had added appeal.

More research is needed to determine whether people's attraction to positive or negative news really does stem largely from how it contrasts with their personal lives.

Bottom line, Soroka says: The study fits into other recent findings that positive stories have more audience appeal than the typical, negative-heavy media menu offers.

"This study suggests," he says, "that there may be an audience for positive content not just in that last story at the end of the half-hour newscast but maybe more broadly at any given point in time."