Advertisement

Held For 20 Days: How N.H.'s Shortage Of Mental Health Beds Erodes Patients' Rights

Imagine you are forced to go to a hospital to receive psychiatric treatment that you don’t think you need. What rights would you have?

That’s the question at the heart of a court battle between the state of New Hampshire, the ACLU and nearly two-dozen hospitals. A ruling in the case could have profound impacts on how New Hampshire treats people who are in a mental health crisis.

The case involves a group of mostly anonymous plaintiffs who were confined in hospital emergency departments.

'Meme'

Meme is 61. She works for an organization that helps people with disabilities and also takes care of her husband who is disabled.

Meme is a family nickname. NHPR is not using her real name because she is afraid of the stigma that might follow someone who has been involuntarily committed for a mental illness.

The events that led to Meme being taken to a hospital are disputed.

It happened last September. Meme says she was suffering from severe stress and anxiety at work and at home.

“It was just the perfect storm of stressors,” said Meme, “so I’d taken the day off and I was recovering at home.”

Later Meme’s adult daughter arrived at her house. She was alarmed by Meme’s condition. She later described it as a “psychotic break.” But Meme didn’t think she needed any help.

They argued. Then Meme’s daughter called 911.

When local police arrived they found Meme agitated and erratic, according to a police report. They said she wasn’t making any sense. Ultimately they told her she had to go to the hospital. Meme refused.

Advertisement

“I definitely did not need to go,” said Meme, “I did not want to go.”

Finally, according to the police report, an EMT instructed police officers to hold down Meme’s arms.

“And the next thing I know they’re stabbing me in the arms with some kind of sedative,” said Meme. “Stab, stab. Next thing I’m waking up at St. Joseph Hospital.”

Meme wakes up in the St. Joseph Hospital emergency room in Nashua. She wants to leave. But the hospital won’t let her.

The reason the hospital can legally hold her against her will is a special petition, known as an Involuntary Emergency Admission petition or IEA. It was filled out by Meme’s daughter and an ER doctor. That form lays out why they each thought Meme was suffering from a mental illness that made her a danger to herself or others.

“My husband came and tried to get me out,” said Meme, “but there was no getting me out.”

After an IEA petition is filed, according to state law, a few things are supposed to happen.

First, Meme should have been transferred out of St. Joseph to a psychiatric care facility.

Second, within three days Meme should have gotten a hearing before a judge. That would have been her chance to argue that she should not be held against her will.

Here’s the problem. There are five psychiatric care facilities in New Hampshire where Meme could have been transferred, but they were all full. On any given day there is a waitlist of around 35 people for a bed. And those hearings where Meme could argue to a judge that she should be allowed to go home are only held at one of those five facilities.

Meme couldn’t leave the ER, and she couldn’t get a hearing. Not until a bed opened up.

“And they won’t even tell you what number you are,” said Meme of the hospital staff. “You ask every day, ‘what number am I?’ ‘Oh we don’t know.’”

The legality of this situation is now being debated in federal court. The question is not whether Meme should have been forced to go to this emergency department in the first place. It's whether her rights were violated once she got there.

Meme ended up spending 20 days locked inside a wing of the St. Joseph emergency department. Her clothes were paper hospital gowns. Her access to visitors, the telephone and even the bathroom was limited.

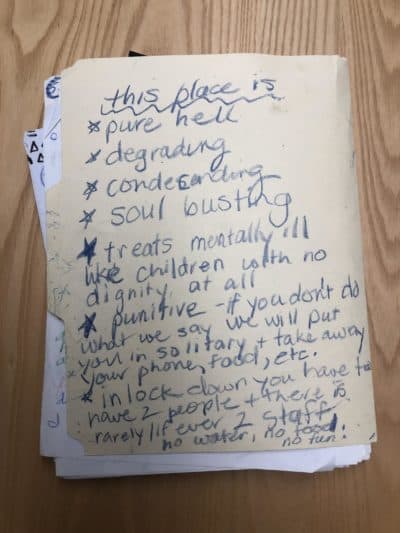

“During my stay, to help keep me sane, I took notes with a crayon and coloring paper because that’s the only thing I was allowed to have to write with,” said Meme.

Pens and pencils were deemed potential suicide risks. And so Meme used a crayon to keep a sort of diary of what she says was a traumatizing captivity.

She wrote about hospital staff who she claims were demeaning.

“Staff call the mental side of the ER, the slums,” said Meme, reading from her notes. “‘Are you slumming it?’ They’d ask each other.”

She wrote about the anxiety of not knowing how long she would be there.

“Still waiting for the phone and still waiting on what number of when I’m getting out of here,” read Meme.

She wrote about how a priest affiliated with the hospital gave her a prayer shawl, but then hospital staff took it away.

“Their premise is that I could’ve strangled myself with it,” said Meme.

Meme said she never had any suicidal thoughts.

A spokesperson for St. Joseph Hospital said they can’t comment on the specifics of a patient’s experience because of privacy concerns. But in a legal filing, the hospital denied any allegations that the conditions of her stay were poor.

On the 20th day, Meme was eating lunch when a pair of sheriff’s deputies arrived in her room. A bed at a psychiatric facility had finally opened up. According to Meme they handcuffed her, put her in a wheelchair and put her in the back of a van before driving her to New Hampshire Hospital in Concord.

Two days later Meme was told she would finally get her hearing.

“You get your husband to bring you your finest dress,” said Meme, “and you go in there, you get a lawyer who’s assigned to you.”

In the end, Meme didn’t even have to argue that she should be released. Meme’s daughter, who had written the petition to involuntarily commit her, didn’t show up for the hearing.

The judge dismissed the petition and Meme was immediately released. For the first time in more than three weeks, she was able to go home. Later, Meme received a bill from St. Joseph Hospital for the cost of her stay – about $2,700.

A 3-Way Lawsuit

Meme is now represented by the ACLU of New Hampshire in a federal class-action lawsuit. Gilles Bissonnette with the ACLU says they want to make sure people in Meme’s situation get a probable cause hearing within three days of being confined, regardless of whether they are at a psychiatric care facility or an emergency room.

“To be deprived of your liberty without any ability to challenge it — it’s wrong,” said Bissonnette. “It’s wrong under our statutes. It’s wrong under our Constitution. And it’s what we’re trying to fix in our lawsuit.”

No one from the state attorney general’s office or the Department of Health and Human Services would comment on pending litigation. But in its legal filing, the state argues that the clock for the three-day requirement for a probable cause hearing doesn’t start until the patient arrives at a state psychiatric facility. The state also argues that hospitals aren’t required by law to hold patients like Meme. In other words, according to the state, this is between Meme and the hospital.

The New Hampshire Hospital Association disagrees. The organization has intervened in this case on behalf of more than 20 hospitals in the state. NHHA president Steve Ahnen says stories like Meme’s are a result of the state’s failure to follow its own laws.

“When a petition for involuntary emergency admission is completed, the patient is committed to the state’s mental health system and has to be transferred immediately,” he said.

Ahnen argues the moment the petition against Meme was filed, the state became responsible for her.

But while hospitals largely agree with the ACLU, they differ on what the immediate solution should be. The ACLU has floated the idea of holding probable cause hearings by video conference inside emergency departments, but hospitals aren’t in favor. They say that would create more of a burden on hospital emergency departments which were never designed to handle these situations.

“It would simply perpetuate a failure of the system to do what the system is supposed to do which is to provide care for patients who need it,” said Ahnen.

One thing everyone agrees on is that this problem is not new. What happened to Meme has been happening to people in New Hampshire for years now. According to data compiled by the National Alliance on Mental Illness, there are approximately 35 patients being held in emergency rooms across the state on involuntary petitions right now.

This story is a production of the New England News Collaborative and originally aired on New Hampshire Public Radio.

This segment aired on October 14, 2019.