Advertisement

As Final Vote On Electrical Substation Nears, East Boston Residents Say State's Approval Process Has Left Them Out

Traducido en español por El Planeta Media.

What’s Diana Cifuentes doing next Monday? The same thing a lot of parents with school-age kids will be doing: juggling.

In addition to doing household chores, the East Boston mom will spend much of the morning and afternoon trying to keep her two kids focused on Zoom school. Later in the day, she’ll try to keep them entertained so she can use the family computer for her own online classes — she’s working toward a certificate in business and finance.

“The kids have to be at home, and I have to be with them,” says Cifuentes, speaking Spanish through an interpreter. “All morning and part of the afternoon they are on the computer taking classes. I don’t have another computer.”

What can’t Cifuentes do next Monday? Watch a seven-hour Zoom meeting about a controversial electrical substation on the banks of Chelsea Creek in East Boston, waiting for a chance to make a public statement about why she opposes the project.

The state’s Energy Facilities Siting Board will take a final vote as soon as Monday, Feb. 8, on whether to approve the substation. The vote will come after a marathon Zoom meeting scheduled for that day from 1 to 8 p.m., with the opportunity for extra time on Tuesday morning.

Residents of East Boston and Chelsea, who have been fighting the project for years, say the siting board’s plan to hold these critical hearings online, on a weekday, during a pandemic is just one more example of how the entire decision-making process around the substation has been unfair.

"At that time many people won’t be able to go because of our jobs, because of our children," Cifuentes says. “They insist [on holding it], which implies that our voice does not matter to them, that our opinion, that our health, that our well-being is not a priority for them.”

Beatriz Yañez is also unable to attend the meeting. After catching the coronavirus last year and spending a month intubated in the hospital, Yañez, an East Boston resident, developed kidney damage that requires her to get dialysis three times a week. She gets the procedure on Mondays, and says it leaves her exhausted — too exhausted to watch an online meeting and give public comment.

Advertisement

But even if it weren't a dialysis day, Yañez isn’t sure she’d be able to participate.

“I don’t know how to use Zoom,” she says, speaking Spanish through an interpreter. “There are a lot of other people who aren’t used to these kinds of technologies and would rather wait until we can do a real hearing in person and can show the force and the strength of the community.”

Electrical substations convert high voltage electricity to a lower voltage for distribution, and we need them to keep the lights on. But many residents of East Boston and Chelsea say building one in a flood-prone area near wooden triple decker homes and a popular playground is a bad idea. They would rather see it built at nearby Logan Airport, which uses a substantial amount of the electricity in East Boston and is both fenced off and better protected from climate change-induced flooding.

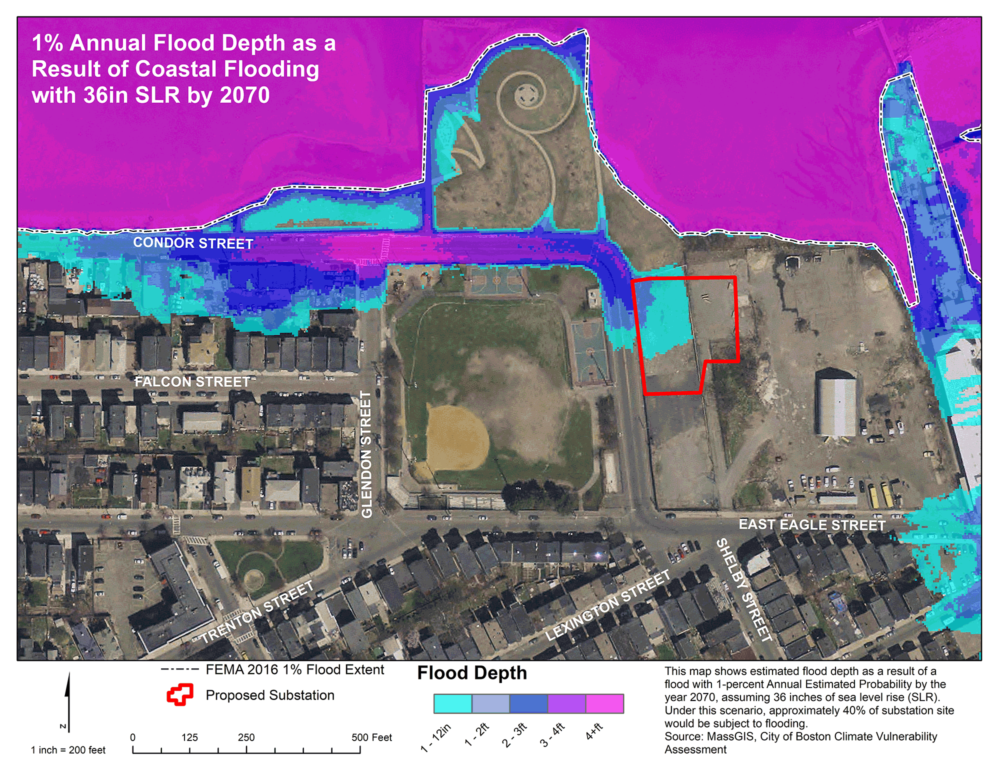

The utility behind the project, Eversource, says the substation will be located outside of the 100-year and 500-year flood zones and therefore poses little risk to the surrounding community. But those who live in this area aren’t so sure.

The street on the west side of the property regularly floods during modest rainstorms, and, as opponents are fond of saying, electricity and water don’t mix. It’s rare, but electrical substations do occasionally catch fire and explode as happened during Hurricane Sandy.

“We are totally opposed to this project,” says East Boston resident Maritza Manrique, speaking Spanish through an interpreter. “And we feel that our voices have been totally ignored.”

Manrique is an early childhood educator who supervises a group of 2 and 3 year olds from 9 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. everyday. During a Zoom interview with WBUR, the kids she was watching popped in and out of the frame, and she periodically had to put down the phone to run after them. Her days are chaotic, and she says she’s trying to find someone to fill in for her at work so she can attend the meeting.

“It’s very important for me to participate, I want my voice to be heard,” she says.

Residents like Manrique, Yañez and Cifuentes say their opposition to the substation isn’t simply a case of NIMBY — or, "not in my backyard." It’s a case of too much in my backyard. East Boston is already home to huge tanks of jet fuel, not to mention air and noise pollution from Logan Airport and heavy truck traffic on Route 1A. On most work days, it's also clogged with commuters fighting to squeeze into the Sumner Tunnel.

The story of the substation is one of environmental justice and who gets to participate -- really participate — in a public process, they say.

Take the Zoom meeting scheduled for Monday. It’s technically the second part of a hearing that was originally scheduled for March 2020, but has been postponed three times at the last minute — twice in the last six weeks because of snow. Community members are frustrated that they have to scramble to rearrange their work and childcare schedules with such short notice.

Despite pleas from the community and several high-ranking politicians to postpone that first meeting — and now this second meeting — until after the pandemic, the state has refused.

“It comes from a real place of privilege. A place of, 'well, this works for us so it should work for everybody.' No, it doesn't work for everybody,” says Roseann Bongiovanni, executive director of GreenRoots, the environmental nonprofit leading the fight against the substation.

“People want to participate. They want their voices to be heard. But they're home with kids on three different devices in three different schools, doing three different virtual [classes]. And so many parents in East Boston are essential workers. How do they expect community members just to take this time off?” she asks.

At a recent GreenRoots event to distribute personal protective equipment and food to residents, Bongiovanni says multiple people showed up to see if they were giving out winter coats because they didn’t have warm jackets.

“This is what Chelsea and East Boston residents are facing: Incredible economic hardship. They shouldn’t have to be thinking about even greater, long-term environmental burdens,” she says. “It’s maddening.”

The state didn’t make anyone available for an interview, but an email from a spokesperson for the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, which oversees the energy siting board, says the board scheduled a meeting spanning day and evening hours so that everyone has a chance to speak before the board takes a final vote.

The spokesperson did not answer a question about why the board won't play pre-recorded public testimony during the meeting for those who are struggling to attend. But he noted that all speakers will be notified of their place in the speaking line, and that the board will "periodically" share a list of the next 15-20 commenters so people will have a sense of whether they will be called in the coming hour.

This isn't good enough for Bongiovanni, who says the board's inflexibility is part of a pattern. GreenRoots has been fighting for years to ensure community members — many of whom are immigrants with limited English skills — get a meaningful chance to participate in the process. Results have been mixed.

Early on, the state didn’t provide Spanish-language interpretation, saying it would be too disruptive. After a lot of complaints, the state began offering it, but it didn’t always go smoothly.

Bongiovanni recalls a siting board meeting in 2019 where the interpreter kept apologizing for her poor translation because she didn't understand some of the technical language.

“She was just saying like, ‘Oh, my God, I'm so sorry. I know I'm doing a bad job at this. I just don't know these words. I don't know what they're saying.’ That’s bad. I felt bad for the translator, it wasn't her fault,” she says.

At another meeting, the interpreter was told to translate from the stenographer's notes, which meant that Spanish speakers heard a delayed readout of the meeting.

“And people were asking, ‘Who's saying this? What is the context?’ ” Bongiovanni says. “Because she was reading it, as opposed to just doing the natural live translation, it was even more difficult to understand.”

The state has improved translation and interpretation services, and made a greater effort to be inclusive, but it’s probably too late.

The siting board tentatively approved the substation in 2017 and has said they are no longer taking public input on whether the project is needed or safe; on their docket now is simply the question of whether Eversource should move the substation 190 feet from one side of the property to the other. (The facility was originally going to be on the eastern part of the parcel near a fish processing plant, but plant owners complained that electromagnetic radiation from the substation would interfere with sensitive machinery.)

The debate over the limited scope of community input erupted during a public meeting in 2019. It was a chilly February night and about 100 people gathered in the East Boston High School auditorium.

It was the first time the siting board held a meeting in East Boston since Eversource had proposed the project five year earlier, and there were rules: people weren’t supposed to talk about environmental justice, language access, public safety, climate change or flooding. They were only supposed to talk about where on the property the substation should sit.

And residents were furious.

“This is a great injustice that the first public meeting that this board is having in this neighborhood limits the discussion to the moving of the project from one place to another, and that it doesn't allow the community and the people who live near it to have a voice,” María Belén Power, of GreenRoots, told the board that night through a Spanish language interpreter.

“All of the people who came here today didn't come for the reason that this plant is going to move 100 or 200 feet. They came here because they are against the proposal,” she said as the audience applauded. “This community, which for the most part is immigrant and Latina has not been included in any part of the entire process until right now tonight.”

Bongiovanni, who was also there that night, called the meeting “insulting” and said it felt like the siting board was just trying to “check a box” and say they took public input.

In an email, a spokesperson for the state says the siting board “greatly values the participation and information provided by public comment and has taken numerous steps in this proceeding to provide meaningful language access for Spanish-speaking residents in the East Boston community in accordance with the Commonwealth’s environmental justice and language access policies.”

But community members and activists disagree. Last month, GreenRoots, along with the Conservation Law Foundation and Lawyers for Civil Rights, sued the federal government for failing to investigate whether the state violated peoples’ civil rights during the substation siting process.

It’s against this backdrop that many residents of East Boston and Chelsea — two communities disproportionately affected by the pandemic and its economic outfall — have asked the state to postpone the upcoming meeting.

Holding it now is “just such a slap in the face considering the moment that we’re in, this reckoning this country is in both environmentally and in terms of civil rights,” says Boston City Councilor Lydia Edwards, who represents East Boston.

“As an agency, if you're expecting people to believe in your legitimacy, in your transparency, then this process, and how you've conducted yourselves in this neighborhood, should be an embarrassment,” she says.

“The more they do things like this, the more people feel like they never had a chance to begin with. And when people check out of the process, they check out of, I think, really, honestly fighting for their neighborhood.”

The only way to really fix the situation, she says, is to start the siting process over and do it right.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story misstated when an interpreter struggled to understand technical terms. The story has been corrected to reflect that the meeting was in 2019. We regret the error.

This story was produced with help from El Planeta’s Tibisay Zea

This article was originally published on February 03, 2021.

This segment aired on February 3, 2021.