Advertisement

Facing Pandemic Toll, Thousands Of Mass. Students Didn’t Apply For Federal Student Aid

As colleges prepare to start fall classes, federal data show stark and unequal declines in the number of public-school graduates in Massachusetts who took one vital step on their way to enrollment — especially after the pandemic took hold.

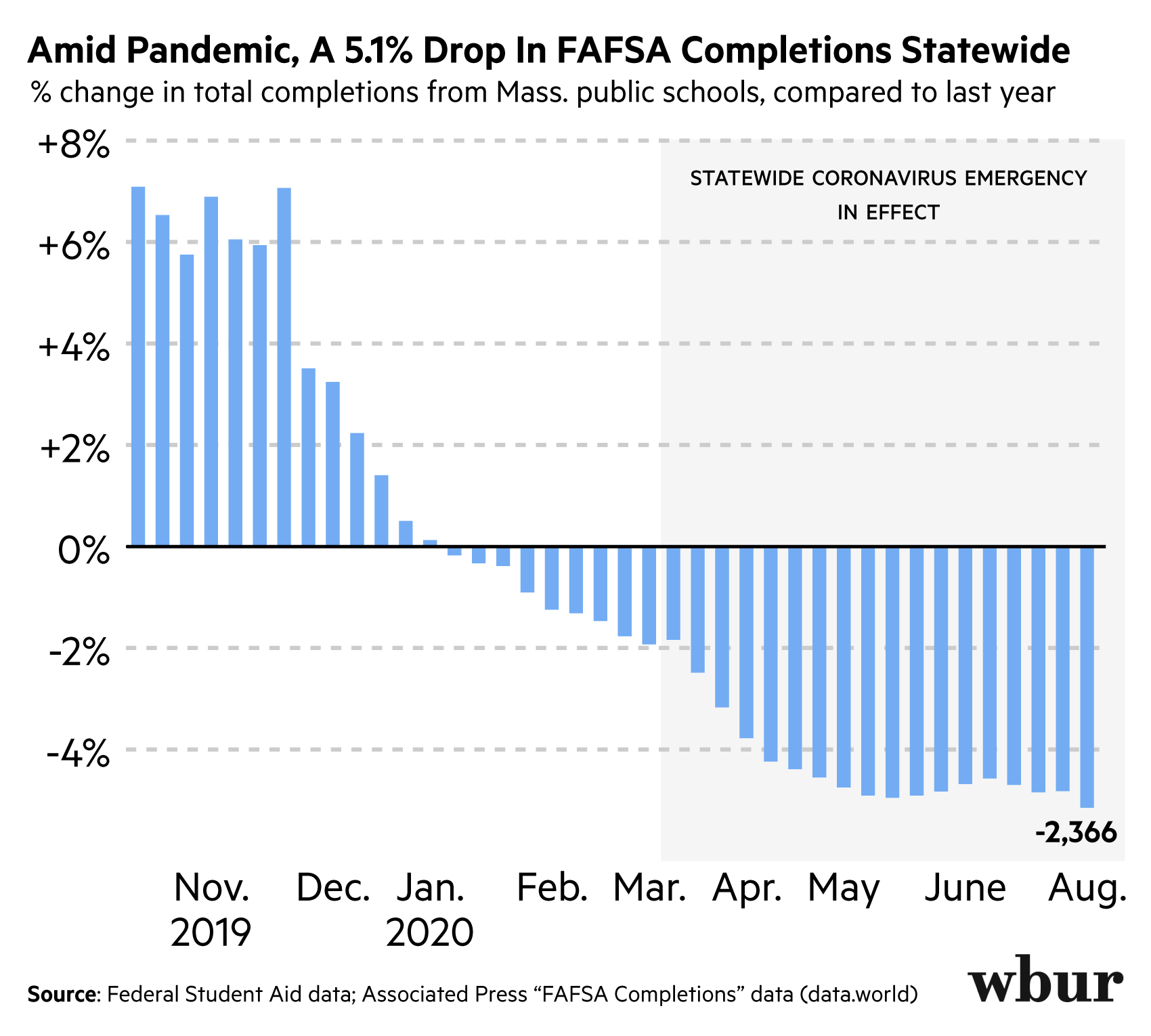

As of Aug. 14, graduates from Massachusetts public high schools had completed 2,366 fewer FAFSA forms this year than they did last year — a drop of 5.1%. That makes the decline in Massachusetts slightly steeper than the national downturn, at 4.3%.

“Am I surprised? Not really,” said Carlos Santiago, the state’s commissioner of higher education. “We sensed that this was going to fall.”

In an interview with WBUR, Santiago proposed a number of explanations for the drop, including mass unemployment, the administrative failure of colleges to guide families through the application process and “so much uncertainty — institutions saying they’re going to open one way or the other.”

Would-be college students have to fill out a FAFSA, a "Free Application for Federal Student Aid," to be eligible for all state and federal grants and loans, as well as many sources of private and institutional financial aid.

More worrisome than the statewide decline are the steeper drops affecting several groups of students most likely to get — and to need — financial support on their way to a degree.

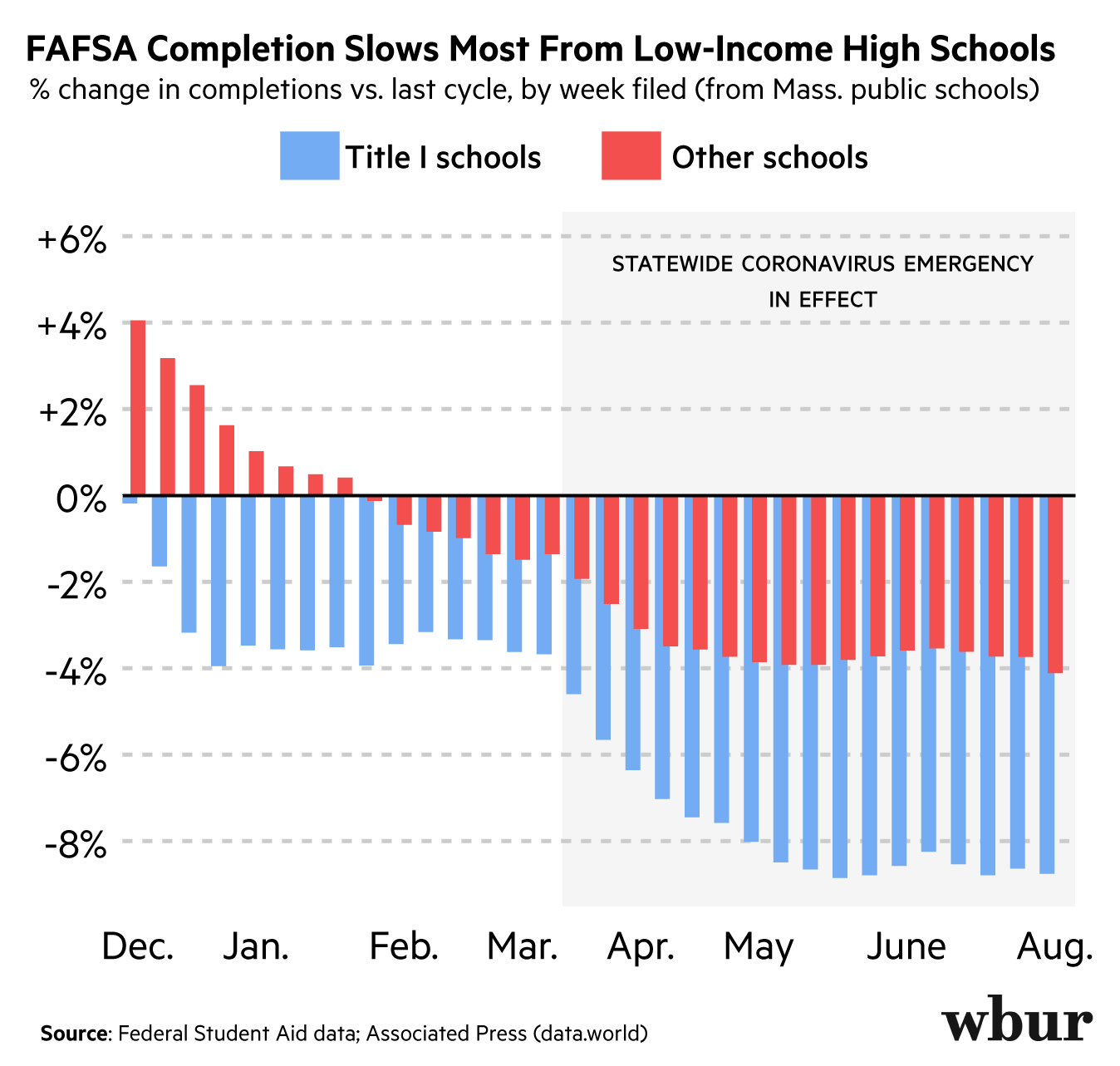

For example, the Massachusetts data include 101 high schools classified as “Title I Schoolwide” by the federal government, meaning generally that at least 40% of their enrollment come from households below the federal poverty line.

Students at those schools quickly fell far behind last year’s pace after Gov. Charlie Baker declared a state of emergency on March 10 in response to the worsening pandemic conditions.

As of mid-August, students at Title I schools had completed 8.8% fewer FAFSAs this year than they did last, compared to just 4.1% fewer from schools without the label.

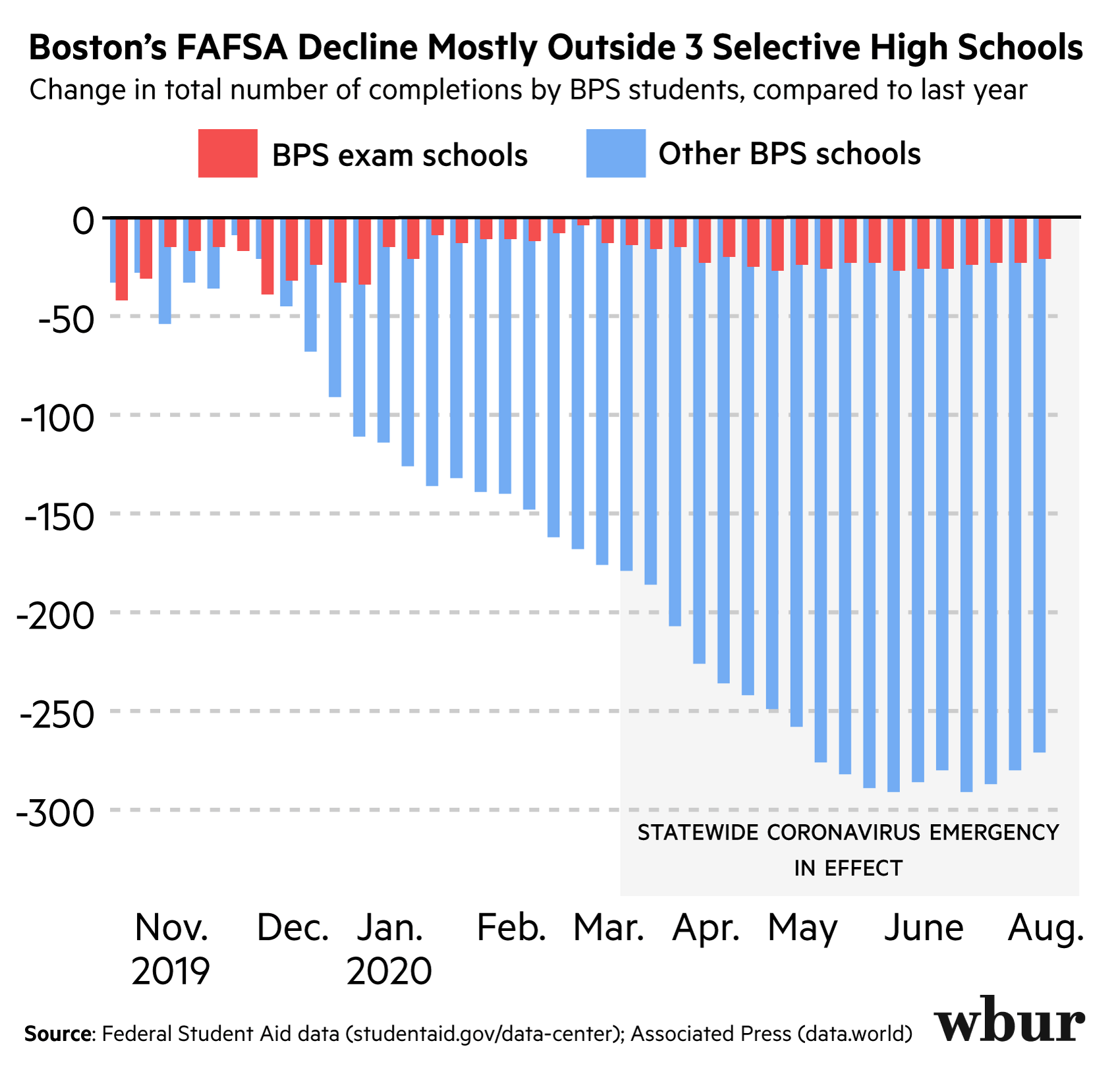

The most striking decline in the completion rate in a single large district came in Boston Public Schools, where federal data show a nearly 13% drop.

Even there, the drop wasn’t evenly distributed.

Boston’s three selective exam schools — Boston Latin, Boston Latin Academy and the O’Bryant School of Mathematics and Science — enroll about 28% of the district’s high schoolers. And yet those schools accounted for just 7% of the district’s nearly 300 fewer FAFSA forms this fall.

Santiago said those disparate declines serve as yet another reminder that pandemics and recessions do discriminate. “Clearly, this is an indicator that COVID-19 is disproportionately hitting communities of color,” he said, giving the example of Latino communities in Boston.

He also worried that public universities and community colleges — which can thrive in moments of mass unemployment — may not have the staff or resources to attract new students this time around or support them once enrolled.

Residential colleges “had a lot of refunds to give back” this spring as they cleared their campuses. And community colleges were under-resourced long before the pandemic, Santiago added. This year, many have laid off the kind of part-time workers who might welcome new students and support their academic progress.

Santiago said his office is trying to direct remaining CARES Act funding at public universities and low-income students, but are also hoping for another wave of targeted federal assistance. “The job loss, the community impact — it’s kind of overwhelming,” he said.

The pandemic conditions also struck at the relationships that can help get something like a FAFSA over the finish line, said Robert Bardwell, executive director of the Massachusetts Association for School Counselors.

Bardwell said many school counselors were already stretched thin in Massachusetts, with unmanageably large caseloads, before the pandemic hit.

“When you’re not with kids for three months, it becomes really hard to help students and families,” Bardwell said. “Because they’re not available.”

Bardwell is himself a long-tenured school counselor in Monson, a small district outside of Springfield. And he noted that the college-going rate was already “trickling down,” both in his community and statewide, before this disrupted spring.

“Students and families are looking at the return on that investment,” Bardwell said. “They see a lot of people with a college degree working in fast food or a grocery store.”

And in certain corners of the state, the pandemic has meant “survival mode,” according to Charles Desmond, CEO of Inversant, a firm that helps lower-income families save for college. (Full disclosure: Inversant is an underwriter of Edify.)

“It’s a whole-family, all-hands-on-deck situation,” Desmond said. “When parents are stressed — which they are — they’re not providing support to students about to step off the cliff going on to higher ed.”

Desmond and Santiago did point to some cause for hope. A report published this week by MassINC showed that graduates of the state’s early-college program have completed the FAFSA and gone on to higher education without interruption at markedly higher rates than their peers.

That program is still small: allowing around 2,300 students in underserved communities to take college coursework early. But Desmond applauded officials’ commitment to keep up investing; the program is projected to double in size next year.

But there still remain worries of a lost generation of students who missed their onramp to college for reasons beyond their control. “The disparities are extremely problematic,” Desmond said.

When he served as chair of the state board of higher education from 2008 to 2015, Desmond said he always returned to the question of how to train the state’s growing communities — immigrants and lower-income districts — to become the workforce of tomorrow.

Now, when the pandemic clears, there’s reason to worry that thousands of people will miss their chance to rejoin the economy on better terms. Taking the measure of the loss, Desmond put the question to federal, state and campus leaders: “What kind of things might we be able to do to get people back on track?”

This reporting draws in part on Federal Student Aid data collected by Larry Fenn and Collin Binkley of the Associated Press.