Advertisement

Reporter's Notebook

Anne Hawley's Best Lead

In April 1994 — four long years after the Gardner Museum had been ransacked and left without 13 irreplaceable artworks — the museum's director Anne Hawley received an anonymous letter. On first read, she was encouraged. Years later, she would remember the moment as the most hopeful she had ever been about recovering her museum's missing masterpieces.

After the 1990 heist, she spent much of her time dealing directly with a frustrating number of cranks and con artists. This letter was refreshing. It was articulate, non-threatening and instructive.

Post-marked from New York City, it read like it had been written by a professional, perhaps a lawyer. In the second sentence, it offered a piece of information that had never before been made public that attested the writer’s credibility: The uniforms the thieves had worn as disguises had not been those of police officers but rather of security guards.

“I want to point out that I had no part in the theft,” the individual wrote, “and really only became aware of it in the past six months. Further, I do not know the identity of the two men who did the actual robbery, I am dealing with a third party. All parties do want a resolution to everyone’s satisfaction… You get the collection and they get some money and immunity from prosecution.”

The plan he offered seemed reasonable enough. The writer claimed the collection of art was still in good condition. They claimed they could facilitate its return if paid $2.6 million and, most importantly, received adequate assurance that there was no risk of arrest while negotiations took place.

“I will make no contacts that could be traced. I fear an overzealous federal agent will try to grab some headlines too soon,” the author of the letter wrote.

Hawley turned over the letter to the FBI's Boston office. Richard Swensen, the special agent in charge of the office, agreed that the writer’s demand seemed reasonable and agreed to order his agents on the case to stand down while negotiations took place.

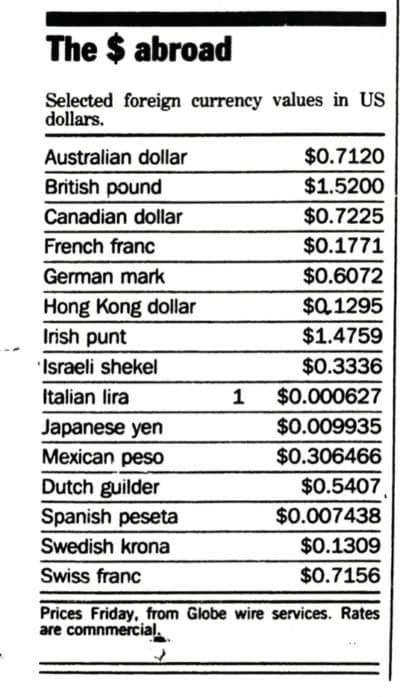

He also approached The Boston Globe to seek its cooperation in the effort. Why? For the negotiations to take place, the letter writer had proposed a novel idea to be assured that the museum and FBI were willing to proceed in good faith. The writer asked that the numeral "1" be inserted in the currency box in the Sunday edition of The Boston Globe.

Advertisement

“For example, this week the LIRA in American dollars is $0.000618,” the letter writer noted. “Using that as a base the following formula must be used to indicate your interest. NOT INTERESTED=$0.000618. AGREE=$1.000618.”

Globe editor Matthew V. Storin said he agreed to cooperate after being approached by Swensen. "I saw it as a community-service decision," Storin said, adding that he cleared the move with William O. Taylor, the Globe's publisher at the time, and made it clear to Swensen that he expected the paper to get the first word if the overture led to the artworks' return.

But Storin was concerned that adding the numeral to the actual value of the Italian lira could have unforeseen consequences. So he decided to place the “1” in the middle of the row, and it ran that way in the Sunday Globe on May 1, 1994.

It took only a short time to know that the anonymous letter writer had seen the paper. The following week, Hawley received a second letter. The writer was encouraged to see that the museum was interested in negotiating an exchange, but was alarmed by what they said was an aggressive reaction by investigators after the museum received the first letter.

Was the museum (and authorities) interested in recovering the paintings, or in arresting a low-level intermediary, asked the second letter. "YOU CANNOT HAVE BOTH," it read, in capital letters. "Right now I need time to both think and start the process to insure confidentiality of the exchange." If the anonymous writer decided it was impossible to continue negotiating, they wrote, they would provide the museum with some clues to the artworks' whereabouts.

But, the museum never received a letter from the same writer again.

What had happened? Had the whole thing been a ruse? In an interview at the time, Swensen was adamant that he had ordered the investigators to stand down while the negotiations took place. One agent assigned to the case at the time confirmed he had been directed by superiors not to investigate dealings with the letter writer, but said other investigators had continued to pursue leads on the case.

Being directly involved in the recovery efforts became a pattern for Hawley. Having taken over as the museum’s director only a few months before the theft and remaining in the job until 2016, Hawley, especially during the years right after the heist, dealt with the theft as deeply as any investigator.

At numerous points she spurred the FBI and the U.S. Attorney’s Office to be more forceful in pursuing the case. At one point, she agreed to contract with a private investigative firm in Washington D.C. to develop and follow leads of its own. Although the FBI acknowledged it was the largest art theft in history, Hawley felt that the FBI wasn’t putting enough priority into the investigation, according to Arnold Hiatt, her friend and a longtime museum trustee.

“The follow through didn’t seem to be what we expected,” Hiatt said of the FBI’s probe. “We expected urgency, and there’d be a time lapse before we got a response. They had, I think, a more junior member of the office on the case. They weren’t indifferent but ... it wasn’t their high priority,” Hiatt recalled in an interview.

Hawley advocated to leaders in government and business as well as members of the public that more needed to be done in the investigation. At one point, she even reached out to the Vatican for a papal appeal for a recovery, especially of Rembrandt’s masterpiece “Christ In The Storm On The Sea Of Galilee.”

In her appeals, she spoke compellingly about what the loss of the masterworks meant to the city and the art world at large. “For people who find it hard to imagine the enormity of this, who maybe are musically-oriented or theatrically-oriented to imagine what if Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony could never be heard again, or what if Louis Armstrong’s work could never be heard again, or what if Hamlet could never be played again,” Hawley said. “I mean, these are works of a civilization that are so important — to remove them is to remove a piece of our civilization.”

Hawley relinquished direct involvement in the investigation in 2005 when the museum hired Anthony Amore, an experienced security consultant, as its director of security. But, Amore says, much of his commitment for recovering the artworks is to bring peace of mind to Hawley, who said before her retirement in 2015 that loss of the most significant piece taken in the theft, Vermeer’s "The Concert," haunts her still.