Advertisement

Paul Farmer's 5 Fixes To Slow Haiti's Cholera Epidemic

Cholera has already killed at least 2026 people in Haiti.

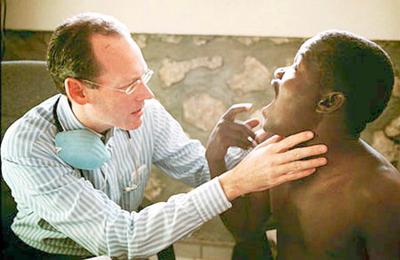

Today, the renowned infectious disease doctor and passionate promoter of decent health care for the poor as well as the affluent, Paul Farmer and his colleagues at the nonprofit Partners In Health write in The Lancet that it's time to get more aggressive in thinking about how to tackle Haiti's escalating cholera outbreak.

In a nutshell, their five "complementary interventions to slow cholera," are:

1. Identify and treat everyone with symptoms.

In a news conference today Farmer said there must be "active case finding," using community health workers to help. "We can't just wait for people to show up."

2. Treat the sick with antibiotics and make the oral cholera vaccine available. (The logistics of getting the vaccine to those who need it is explored on NPR today.) "Rehydration without antibiotics is not a good idea," Farmer said. "We're arguing for anitbiotics for all comers."

Farmer said there is resistance from the public health community on this aggressive approach to treatment. "We are seeing resistance," Farmer said. "I'm not going to be arch about it, the resistance is not coming from patients and their families, it never does. There's great doubt around logistics and cost. In a battlefield situation, what do you do first?"

Still, he says, there is vaccine available: “Based on our discussions with experts, there are potentially 2 million doses of the cholera vaccine available. In the face of a regional, long-standing epidemic, it does not seem too much to ask to start ramping up that effort to make available significantly more doses of vaccines. I would have expected more engagement on some of these tough logistic questions – how do we have the vaccine, how do we distribute it, make it more available, etc.”

3. Remedy Haiti's problem with "water security" (i.e. — not having enough clean water) and improve sanitation

4. Make sure all efforts to deal with specific diseases (HIV/AIDS, cholera) include a focus on strengthening the country's overall health care system, particularly primary care

5. Raise the bar on health care goals in Haiti. "No cholera epidemic is local for long," they write. "The goals of responding to cholera in Haiti should look the same as the goals of responding to cholera in the Dominican Republic or Florida, to name two settings already touched by what is widely termed the Haitian epidemic."

Farmer noted: "You don't make one standard for poor countries, a different one for middle income countries and another one for affluent countries."

"Although cholera had not been documented in Haiti for many decades," Farmer and his colleagues write in the Lancet, "it has long been the most feared waterborne disease. Health-care providers working in informal settlements and refugee camps, both especially vulnerable to waterborne diseases, know that cholera's profuse secretory diarrhoea can shrivel a healthy adult in less than 6 h. Case-fatality rates of untreated severe cholera can reach 50%, while most agree that aggressive case management can drop this figure to under 1%."

You can listen to the entire news conference here.