Advertisement

Despite Bad Grades, Many Boston Teachers Stay In Class

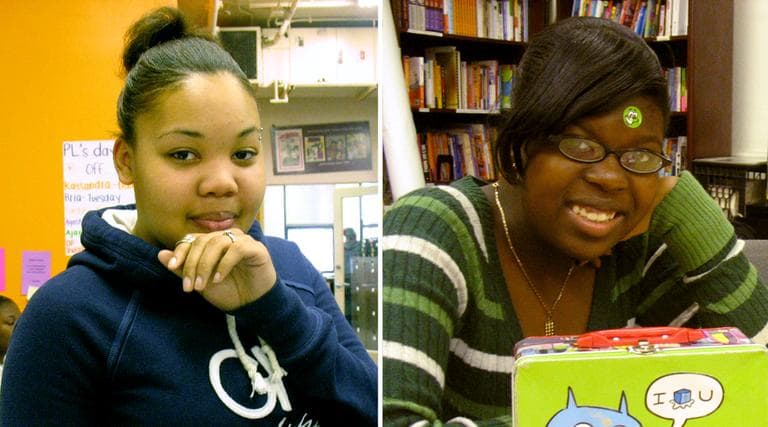

Ask any student if they’ve had a bad teacher and they’ll tell you stories. I sat down with a few Boston high school students after school where they work together on a magazine for teens.

"I’ve had this teacher, she’ll like cry in class for the whole entire period," says DeShannah Temple, a sophomore at Hyde Park High School, "crying about her life, how much they don’t do nothing for her at the school. Like, if you feel that way, why not just quit?"

Her friend Ehis Osifo, a sophomore at Boston Latin School, cuts in: "OK, so this was my math teacher, so he would make us do the homework and then somewhat teach us the next day what the homework was on.

This phenomena in Boston schools is called The Dance of the Lemons. Essentially it’s moving bad teachers around to different schools instead of firing them.

"What he would teach us would be like the bare minimum and then on the tests he’ll give us extremely hard questions that he never went over in class because he spent the entire class talking about his life and how he played soccer as a child."

You see there’s this phenomena that's happening in Boston Public Schools and it's called The Dance of the Lemons. Essentially it’s moving bad teachers around to different schools instead of firing them.

The dance goes like this: I’m the principal and I have a teacher who isn’t making the grade but I think it would be too hard to help them improve. So instead of giving them a bad performance review, I give them a satisfactory evaluation and strongly suggest they volunteer to go into what’s called the excess pool — a pool of excess teachers. Schools must select from the excess pool when hiring new teachers. And that is the dance of the lemons.

"I have heard that terminology," Boston Superintendent Carol Johnson says. "What we’re trying to do is stop the dance, not move people from place to place, but expect principals and headmasters to do a high-quality review and make the tough decision."

Although Boston’s not the only district that shifts around bad teachers, it’s been a known problem here for a while. Johnson’s predecessor, Thomas Payzant, who led BPS for 11 years and is now at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, says he knows it went on under his tenure. But he’s sympathetic to principals who don’t have the time it takes to document and fire bad teachers.

Advertisement

"The amount of work that a principal has to do with data and other evidence of lack of performance and meeting standards can take hours and hours of time," Payzant says.

Five years ago, under Payzant, Boston Public Schools only fired 12 teachers one year. The rate has steadily improved under Johnson as she works to conduct more evaluations, the cornerstone to removing a teacher. Last year 57 teachers were fired or resigned due to bad evaluations. That’s still only around 1 percent of teachers fired each year; the statewide average is 8 percent.

Johnson pulls out a bright orange book the size of a small paperback. It’s the 255-page union contract. She turns to the pages that spell out how to fire a bad teacher.

Johnson explains that the procedures to get a tenured teacher fired are really complicated. A principal must rate them as unsatisfactory and document why a teacher is considered failing. This can be subjective because the state has never used student tests scores in teacher evaluations. New regulations will require principals to use them in the future. And this proposed new system will also speed up the firing process — but only if administrators take that first step. And Johnson knows many don't, and thus bad teachers are tolerated in the classroom.

"And right now, our process is somewhat cumbersome," she says. "We have to go through so many steps, meet so many deadlines, that it makes it really hard to get to the process and so that’s very frustrating."

"It’s only cumbersome if you’re lazy," Richard Stutman, president of the Boston Teachers Union, counters. "It takes, I think reasonably, a sophisticated administrator who is somewhat diligent two or three hours to do a full evaluation of an unsatisfactory or a needs-improvement teacher. I don’t really think that’s an onerous responsibility."

Stutman says for bad teachers to be called "lemons" because they are in the excess pool is insulting because they haven’t done anything wrong.

"It is impossible to get into the excess pool if you have an unsatisfactory [evaluation]," Stutman says. "The school department can’t have it both ways. They employ the principals, the principals have all sorts of authority under the state ed reform law, and if they give the person a satisfactory, then shame on them for calling that person a lemon. They should look in the mirror."

There’s a lot of blame to go around. Only 41 out of nearly 5,000 teachers were rated as unsatisfactory by their principals in the 2008-09 school year, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Also one-quarter of schools didn’t turn in a single evaluation for a two-year period. Johnson says she is beefing up the evaluation system with a team of people dedicated to help principals.

Studies show outstanding teachers produce higher-performing students. Boston students Brittney Edwards and Osifo agree.

"Good teachers, I feel like they take an extra mile that they’re not required to take, but that just makes them so much better," Edwards says. "Ones that push you and make learning fun."

Osifo adds: "I feel like the best teacher, like when you graduate from high school, they are the ones you remember."

And the bad teachers unfortunately can be hard to forget.

This program aired on May 25, 2011.