Advertisement

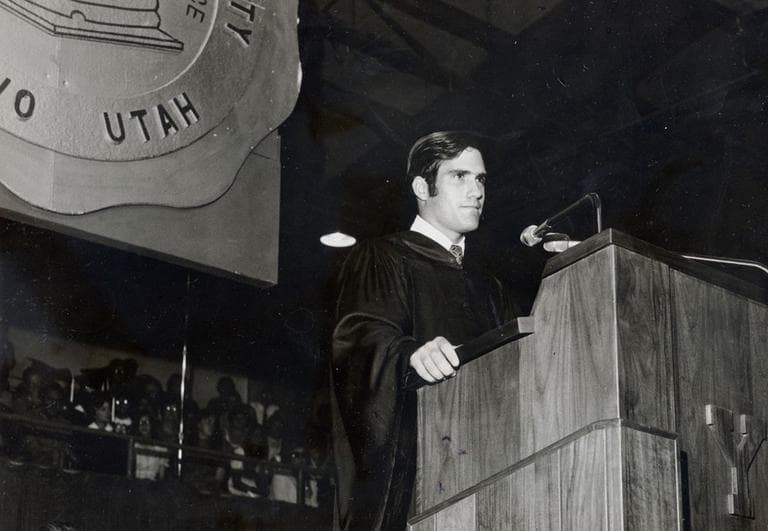

Romney's Harvard Years: An Earnest Traditionalist

The first entry of a six-part series

BOSTON — Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney started his political career in Massachusetts, but his years at Harvard University first brought him to the state. During his time at Harvard, he struck many of his classmates as unusually optimistic and not at all jaded, even though he arrived on campus at a time of great societal ferment.

[sidebar]

WBUR traces our state's long connection to the GOP presidential candidate. A six-part series:

- 11/22: Romney's Harvard Years: An Earnest Traditionalist

- 11/30: Romney's Bain Years: Turnaround Specialist-In-Chief

- 12/6: At Belmont Temple, Romney Was An Influential Leader

- 12/15: Romney's Jobs Record As Governor Is Up For Debate

- 12/20: Analyzing Romney's Leadership On Health Care

- 12/27: Romney As Executive: Big Dig Crisis Management

Timeline: Mitt Romney's life and career

Related: WBUR's complete Election 2012 coverage

[/sidebar]

Anger over the war in Vietnam was at full throttle in 1971, when Romney began his first year at Harvard Law School.

Protests were common on campuses nationwide, and Harvard was no exception. Just two years before Romney arrived, students protesting Harvard's stance on the war had taken over an administration building in Harvard Yard. Police eventually stormed in with billy clubs and Mace to arrest them, and that incident was still a fresh memory for the often cynical and skeptical student body.

Not Romney.

"Mitt was dramatically different from that," recalls Garret Rasmussen, one of Romney's law school classmates. "He was entirely positive, entirely enthusiastic, not a complaint in the world. He thought it was wonderful to be at law school. That's what stood out about him."

Advertisement

In fact, Romney was a supporter of the U.S. role in Vietnam. He was unlike many of his classmates in other ways, too. He hadn't gone to an East Coast prep school or college. Instead, he'd grown up in Michigan, attended Brigham Young University in Utah, and been a Mormon missionary.

Rasmussen, who's now a partner at a Washington, D.C., law firm, says Romney had a simplicity and straightforwardness that seemed distinctly Midwestern.

"More like a farm boy than a sophisticated New Yorker," he says. "That was the impression. Not that he's dumb, not that he's naive. It's more that he's a country boy more than a city sophisticate."

But Romney was no rube. His father, George Romney, had been the governor of Michigan, the CEO of American Motors, and was in President Nixon's cabinet when his son started law school. That made the Romney name a prominent one on campus. But Mitt Romney was only one of numerous Harvard students from august, wealthy, connected families. His classmates included the son of the U.N. secretary general and the great-granddaughter of Theodore Roosevelt.

"Mitt didn't stand out in the class as some kind of political superstar," says Ron Naples, who also went to Harvard with Romney. "He was one of the guys. He was a guy that I think most people came to know and like." Naples wasn't a law school classmates of Romney; they were business school classmates — part of a tiny, elite group of students earning degrees at both Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School.

Howard Brownstein was also in that group, and he says Romney's short-haired, clean-cut, buttoned-up look was a distinguishing feature.

"It wasn't unusual that you would see fellow students who looked like radicals, and Mitt didn't look like that," Brownstein recalls. "Mitt looked like a pretty straight, conservative guy. He was clearly one of the more traditional-looking and -acting people at the campus. I wouldn't say a stiff. I would say just traditional."

Even Romney's home life was traditional. When he enrolled at Harvard in his mid-20s, Romney already had a wife and two children and even owned a house in nearby, well-to-do Belmont. Brownstein was an occasional guest.

"We were used to living in dorms and apartments and he was sort of living a few years ahead of the rest of us," Brownstein says. "Here was a guy, he was already married, he was living in a nice suburban home. He kind of reminded us of the homes we grew up in."

Even with his family obligations, Romney made time to socialize. He played basketball at a gym in a church in Harvard Square and went to group dinners at restaurants like Joyce Chen and Legal Sea Foods and Cafe Budapest. But he didn't drink, true to his Mormon faith, and Brownstein says you'd never hear him put someone down or utter a curse word.

"Mitt is nothing if not earnest," he adds.

Conservative, old-fashioned, seemingly guileless, so sunny and self-assured he might be mistaken for naïve. That's how Romney's Harvard classmates remember him. And that's in many ways the Romney of today: the classically handsome guy with the beautiful family and nearly perfect life. Someone who seems to expect everything to go right, and for whom everything usually does. But back at Harvard, Romney had another quality — something that's rarely used to describe him these days.

"What impressed me was he had a warmth that just connected to you," says Mark Mazo, who was in a five-person study group with Romney at Harvard Law.

Mazo is aware that Romney the campaigner is often criticized as stiff, cool and unable to relate to regular people. But Mazo, now a Washington, D.C., lawyer, had a recent interaction with Romney — after not having talked to him in about 30 years — that has him standing his ground. At a Romney fundraiser in Washington a few weeks ago, Mazo reintroduced himself.

"I said, 'Governor, it's been a long time since Harvard Law School. I'm Mark Mazo.' And he looked at me and he said, 'Mark Mazo! Mark Mazo!' He said, 'How's Fern?', a reference to Mazo's fiancee in law school, now his wife.

"And my first thought was. 'That was darn good staff work!' " Mazo recalls, explaining that he had RSVPed that he'd be coming and he assumed Romney's handlers had looked up personal details about guests for Romney to sprinkle into conversation.

"But then he said, 'Mark, I remember when you came to dinner at my house,' " Mazo continues. "He said, 'I remember what we had to eat. We had pork chops.' And he was right. That is what we had to eat, was pork chops. I don't know how he remembered it. And there was no amount of staff work that could have filled him in on that one. He actually remembered, which I was blown away with."

Maybe that's nothing more than a sign of a good memory. But Mazo believes it shows that Romney has a more personable, human, down-to-earth side than he reveals in public, or that's captured in soundbites, and that he generally gets credit for. Still, then and now, Romney had a fundamental sense of reserve.

"Mitt was not a quipster," says Janice Stewart, one of a small number of women in Romney's business school class. "He did laugh. I mean, he had a beautiful smile and he laughed, but he wasn't a humor leader. He would never be the one to think of the quip, but if somebody else made a good quip or a good line or something in class he'd laugh at it. But was not the one who was going to invent the laughter."

Stewart, who went on to work in management for Xerox, says there was something else Romney was not: "He was not one of the three or four that we thought of as being the ultra, ultra, ultra bright ones. He was not the brainiac kid in the room."

Brownstein, who was in Harvard's dual degree program with Romney, agrees with that assessment.

"There were some people on that campus who, you know, when they thought, their brain lit up the room," he says. "You could talk to them in a dark room and it would be like sunshine. Mitt was not one of those. Mitt was not the guy who was going to be president of Law Review and be first in the class and go write the Uniform Commercial Code."

He was certainly bright and hard-working, they say, but he was just one of many smart, driven Harvard students. What did distinguish Romney was his participation in that dual-degree program. Out of roughly a combined 1,300 students in his business and law school classes, just 15 graduated from both.

"When we told people we were in the JD/MBA program, you were kind of looked upon as somebody a bit special," recalls Brownstein, now a corporate turnaround specialist.

He says that whereas Harvard Business School puts its students through a practical, problem-solving regimen of analyzing real business case studies and deciding what they would do if they were in charge, "the law school is teaching you at a more theoretical level."

Together, the two educations gave students a detailed knowledge of the law and the government regulatory system, as well as a deep understanding of how to run a business. And those dual-degree graduates were some of Harvard's most sought-after recruits. Stewart describes the power of the twin degree this way: "If you came out of that MBA/JD joint program, it's hard for me to imagine a task that somebody could have could put in front of you that you couldn't do, other than brain surgery. But running anything — running a company, running the Olympics."

Both of which Romney went on to do.

"A lot of us did the safest thing," Rasmussen says. "We would go work for the Boston Consulting Group or Morgan Stanley. Those were the big places that hired out of business school. If you wanted just to play it safe and get rich that's what people did. Or out of law you go to Sullivan & Cromwell in New York or Cravath and things should work out for you. But Mitt was willing to start something on his own."

Right out of Harvard in 1975 — after graduating with honors from the law school and in the top five percent of his business school class — Romney did make a conventional career move by becoming a well-paid consultant. But he later took riskier moves that ultimately made him wildly rich and also complicated his image. Compared to the person his classmates recall from four decades ago, the Romney of 2011 is often criticized as a more hollow, opportunistic man with flexible convictions.