Advertisement

A Rare Disease Known As 'E', And The Invisible Injuries It Leaves Behind

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M5cfl2Rwze4

Today, Feb. 29, is a rare day on the calendar, and fittingly, it is officially Rare Disease Day around the world.

There are thousands of rare diseases out there — between 5,000 and 7,000, according to the European Organisation for Rare Diseases. And though each disease is rare, put them all together and they affect 6-8% of the population, the European figures suggest. About half the diseases are inborn and half come later in life, from infections and other causes.

Surely one of the most insidious diseases to strike later in life is encephalitis, a potentially devastating brain inflammation known colloquially in its community of patients and caregivers as "E." I've heard mainly about encephalitis as a doctor's nightmare, because it can be both deadly and hard to diagnose, and as a staple of summer news: Every year brings a report or two of a Massachusetts resident stricken by the Eastern Equine Encephalitis carried by mosquitoes.

But with the release of a new survey of some 250 patients with encephalitis and their family members, I now have pictures in my mind to go with the letter E:

- An encephalitis patient who tries to light his cigarette with this thumb, forgetting that he needs a lighter to flick.

- high-flying, 38-year-old senior vice president of a global company who delivers a presentation in southeast Asia and just two hours later suddenly finds herself unable to walk, to speak, to do anything but lie shivering in a paralyzing fog.

- "Invisible residuals:" You may seem fully recovered to others but still suffer from lingering problems with memory, relationships, problem-solving, multi-tasking. The report drew its title from this survivor's quote: "I look normal and act normal but it’s a very hard thing to have, as people don’t know of it...I tell friends and family but they seem to be thinking that it’s two years now and I should be better, which is of course what I feel, so it makes it very hard, but as my family keeps telling me, I am still here, just not quite the me I remember."

The report was compiled by the non-profit Encephalitis Global and by Inspire, a company that manages online patient support communities for a wide variety of diseases. We reported on the Inspire survey of parents of premature babies last year, and the encephalitis survey is yet another exercise in consciousness-raising: It compiles the experiences of patients and their families in order to help both medical staffers and the general public understand what they go through — in particular, the special pain of being misunderstood.

Advertisement

From the executive summary:

According to the survey, encephalitis creates a negative psychological impact on the patient due to its invisibility and often the misdiagnosis of it altogether.

- Survivors and caregivers share a high degree of torment and anger about the frequency of misdiagnosis and the lack of adequate follow-up care after proper diagnosis. This includes caregivers of those who did not survive. More than 20% of survivors responding to the survey say they were misdiagnosed, sometimes as long as two years later. Feelings of being dismissed (often stemming from misdiagnosis) can significantly complicate a survivor’s recovery, especially those whose doctors suggested they were mentally ill.

- "The initial diagnosis is often incorrect, as symptoms may be attributed to another diagnosis, such as the flu or even a psychiatric disorder," said [the Mayo Clinic's Dr. H. Gordon] Deen, who described encephalitis as a "devastating" rare disease.

- Although neuropsychological exams were not always ordered, about half of the patients who did take one benefited from doing so. This, perhaps, is from discovering the root causes of “issues” experienced. For example, one survivor indicated that the exam concluded that her problem-solving abilities were significantly compromised from the impact of encephalitis. Seeing those results helped her understand her limitations better and develop adaptive skills.

- "When a patient understands their residuals from this cruel illness, they are better equipped to incorporate strategies and coping mechanisms into their daily activities," said [psychologist Steven W.] Sliwinski. "Without this information, a patient is more likely to develop the feeling of despair and a sense of being damaged goods. These feelings are likely to hinder progress at repairing the damage and may lead to co-morbid disorders such as depression."

- Because encephalitis is often not recognized as an acquired brain injury, this impacts the degree to which aftercare and therapy is recommended, thus slowing recovery. Unfortunately, even though aftercare and therapy have significant evidence as being beneficial to recovery, health insurers often deny this treatment. The lack of research and frequency of misdiagnosis likely contributes to the denial of insurance coverage.

- Support is vitally important to successful recovery: the support of family and friends, of psychotherapy, and of online communities. Online communities serve a critical role to encephalitis survivors because there is such a lack of available information about the disease, about its lasting effects, and about recovery and effective aftercare. More than half of respondents said that communication via online communities reduces their feelings of isolation and neurosis. More than half learn coping strategies for dealing with the illness and its residuals from online communities.

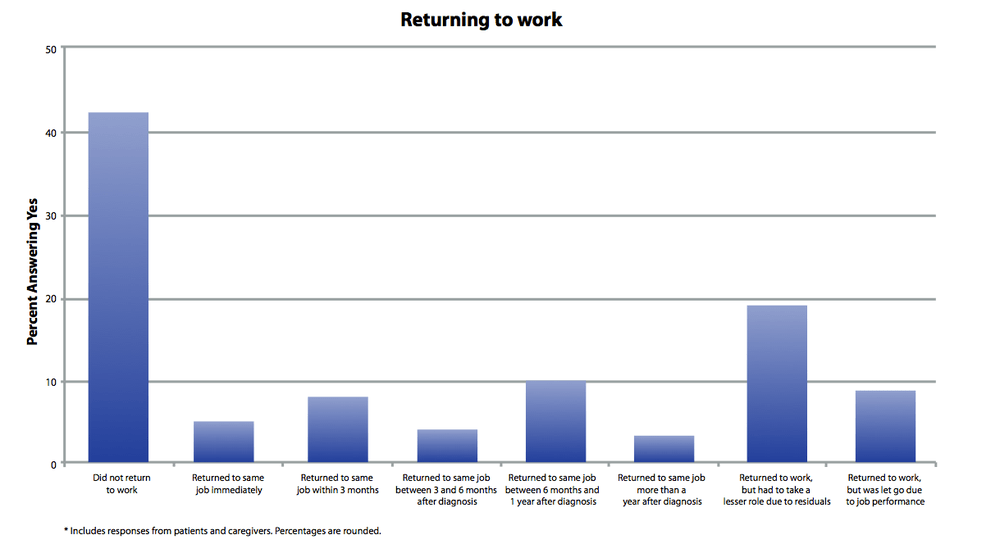

I had never heard the term "residuals" used this way before, and I imagine it could be applied to a great many forms of neurological aftermath, from "chemo brain" to Lyme Disease. This chart struck me as particularly daunting:

What could be more depressing than a compendium of stories of people whose lives were suddenly ravaged or ended by a rare brain infection? So let us end with a digital ray of light, the prospect that the Internet's famed ability to bring together far-flung people who share a rare characteristic could lead to better research on encephalitis.

The report quotes Dr. H. Gordon Deen of the Mayo Clinic, an encephalitis experts, as pointing out that the disease is hard to study because it is so rare that even the largest medical centers see very few cases. But now, he says, "Groups such as Encephalitis Global, Inc. are using Internet support groups to assemble themselves in large numbers (1,500 to date) and present their own statistics to increase awareness among medical researchers."

The full text of the new encephalitis report is here.

This program aired on February 29, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.