Advertisement

Inspiring Words And Modern Hippocratic Oath For Doctors-To-Be

Tufts Medical School held its annual "White Coat" ceremony this weekend to induct some 200 new students into the profession — and yes, to give them the white coats that will mark them ever after as medical staff.

The event included a poetic speech, excerpted below, by Dr. Beth Lown, medical director of The Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare, and the students recited the "Modern Hippocratic Oath."

"The what?" I asked, ever the last to know. "There's a new oath?"

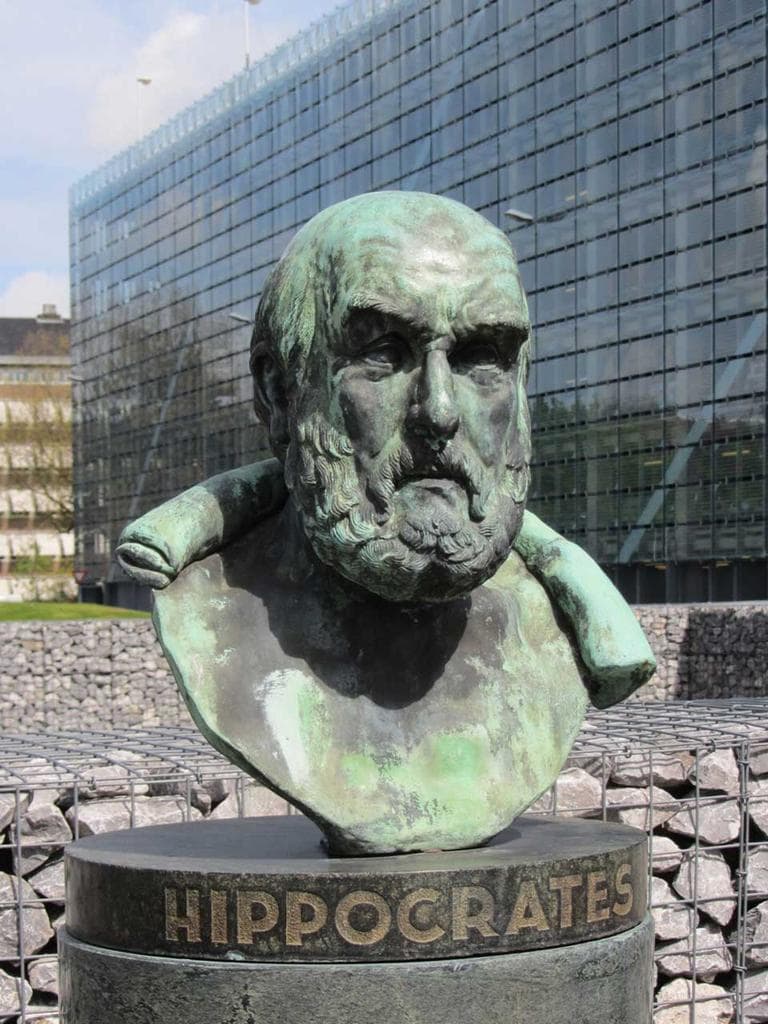

Turns out controversy has long swirled around the 2500-year-old oath, as Nova describes in a fascinating 2001 look here. Nova includes the full and quite pagan original text, beginning "I swear by Apollo Physician and Asclepius and Hygieia and Panaceia and all the gods and goddesses, making them my witnesses, that I will fulfill according to my ability and judgment this oath and this covenant."

It is a mix of eternal and utterly outdated pledges, and my eyes widened when I read that it includes a sentence relevant to the physician-assisted suicide measure on this November's Massachusetts ballot: "I will neither give a deadly drug to anybody who asked for it, nor will I make a suggestion to this effect."

The modern version has this instead:

Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life, all thanks. But it may also be within my power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty. Above all, I must not play at God.

The modern oath, which is now extremely widespread, was written in 1964 by the late Dr. Louis Lasagna, Academic Dean of the School of Medicine at Tufts, and it exudes far more compassion, nuance and indeed humility than old Hippocrates. It includes:

I will apply, for the benefit of the sick, all measures [that] are required, avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism.

I will remember that there is art to medicine as well as science, and that warmth, sympathy, and understanding may outweigh the surgeon's knife or the chemist's drug.

I will not be ashamed to say "I know not," nor will I fail to call in my colleagues when the skills of another are needed for a patient's recovery.

The spirit of Dr. Lown's speech jibed well with the modern oath; most of it is below, broken into five parts:

Wonder and curiosity

Here is my first celebration hope for you – that you cultivate a sense of wonder and curiosity, tenderness and respect for the patients you will see as you learn, train, practice, teach or do research.

How can one not be curious in this amazing world we inhabit? Faith Fitzgerald, Professor of Medicine, Associate Dean of Bioethics and the Humanities at U.C. Davis wrote a wonderful article about curiosity that was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 1999. She describes her ambition as a young attending to teach interns and residents that there was no such thing as an uninteresting patient, so she asked them to pick their “dullest” patient for bedside teaching rounds.

The resident chose an elderly woman who had been evicted from her apartment and had nowhere to go. She appeared to be suffering primarily from isolation and abandonment, but she had no big history to tell, no stories to share. She answered questions with one word sentences. Dr. Fitzgerald was starting to sweat. This patient seemed singularly uninteresting… until she asked the patient how long she had lived in San Francisco: “Years and years,” she said. Was she here for the earthquake? No, she came after. Where did she come from? Ireland. When did she come? 1912. Had she ever been to a hospital before? Once. How did that happen? Well, she had broken her arm. How had she broken her arm? A trunk fell on it. A trunk? Yes. What kind of trunk? A steamer trunk. How did that happen? The boat lurched. The boat? The boat that was carrying her to America. Why did the boat lurch? It hit the iceberg. Oh! What was the name of the boat? The Titanic.”

Ask and listen

When you put on your white coats, you will be crossing a Rubicon, a turning point of commitment to the profession of medicine. Unlike Harry Potter, you will be wearing a “Visibility Cloak.” At first, you will feel the same, but others will view you differently whether you feel ready or not. I remember one first year student in our Patient-Doctor 1 course telling me he wished he could plaster a sign on his forehead saying, “No Medical Knowledge!” so anxious was he about others assuming his medical competence. But very soon you will be asking patients questions and they will be sharing details about their lives that they would share with no other stranger. You will hear about abdominal pain, chest discomfort, shortness of breath, yes, and you may hear the joy and pride in the voice of a parent whose child is entering medical school. You will also hear the pain of conflict, loss, and suffering if you care to listen.

Here is my second celebration hope for you – that you honor the trust of patients by caring enough to ask and to really listen. Listen to their stories about their lives, their hopes and joy, their fears and desperation.

Advertisement

Listening is not so simple – it is a learned skill that must be continuously honed. It is also a powerful diagnostic tool. It is often said that 70% of diagnoses can be made based on the patient’s history alone. But beyond diagnosis, as fun and ever-fascinating as that is, listening is a therapeutic tool; perhaps one of our most potent but under-rated, non-FDA approved therapies. Because caring enough to ask and to really listen to the patient’s story is the foundation of compassionate relationships and the relief of distress and suffering. And that is the pathway to healing.

Balance

Here is my third celebration hope for you: that you find ways to sustain your empathy and compassion for others without overly joining in their suffering such that you deplete your capacity for this process, nor overly distancing to protect yourself from distressing emotions. That you find sources of personal balance and equanimity.

Sir William Osler, often called the “father” of modern medicine, wrote an essay called “Aequanimitas” in 1889 as he was leaving Philadelphia to become the first Chief of Medicine at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. In this essay, he extolls the virtues of imperturbability. “Cultivate, then, gentlemen, such a judicious measure of obtuseness as will enable you to meet the exigencies of practice with firmness and courage, without, at the same time, hardening "the human heart by which we live."

Some find a wellspring of equanimity in being with friends and family, some in exercise, the arts, religion, spirituality, meditation, enjoying nature, gardening. I started reading and writing poems when I was an intern to make sense of my experiences and to honor and sometimes memorialize my patients. Whatever works for you is fine, but you’ll have to consciously carve out time for activities that will sustain and renew you.

Cure sometimes, heal often and care always

We have to work hard to bridge these gaps in culture and experience. At other times, it may be hard to be compassionate because you feel frustrated or angry – at patients who are seeking or diverting drugs, patients who don’t change unhealthy habits, behaviors or addictions, who don’t take their medicines and come to clinic or are admitted and readmitted to hospital with all of the complications that then ensue. These situations will try your patience. It’s okay to feel this way, but you still have to try to understand patients’ worlds and experiences. Otherwise you will be completely ineffective in helping them change. I will tell you a secret it took me a long time to learn: you cannot prescribe change however much you wish you could. You can only try to understand the patient’s perspective well enough to guide the patient so he can find within himself (or herself) the capacity to change, and to help them find support from others. This takes caring enough to ask and to listen.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'You cannot prescribe change, however much you wish you could.'[/module]

Patients and families may become angry with you. Sometimes with good reason – when an error is made, for example and a patient is harmed. Fortunately, Massachusetts is piloting models for transparency, disclosure and apology so patients, families and physicians can begin to heal more quickly from these tragedies. But sometimes it may seem that no matter how hard you have tried and how many hours you’ve worked, it just isn’t enough when a patient has a poor outcome.

I had known my patient, Mrs. S for many years, seeing her for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and other primary care issues before she developed metastatic osteosarcoma, a malignant bone tumor. I knew about her son’s difficult marriage and divorce and I knew that Mrs. S and her husband had folded him and her grandson back into their home, putting up new wallpaper and turning one of their rooms into a nursery. I knew what stuff this woman was made of – kindness, love and generosity. She never complained and always seemed to manage a smile even after chemotherapy and multiple surgeries. And then, we exhausted the possibilities for extending her life. We engaged hospice to help manage her pain and nausea and I visited her weekly at home where she occupied a hospital bed in the center of her living room surrounded by her sons, daughters and grandchild. She looked comfortable, but the youngest daughter wanted more to be done, including a feeding tube, insisting that her mother “not give up.” But Mrs. S had made her wishes about this clear. There were to be no heroic measures, no feeding tube, no readmission to hospital, no CPR.

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'This daughter was feeling anguish about whether she had been a strong enough advocate for her mother.'[/module]

After she died, her youngest daughter wanted to see me along with her father, angrily insisting that I could have worked with the oncologist to recommend more aggressive treatments earlier in her mother’s course to prevent the progression of her disease. I spent hours preparing for the meeting, reviewing our management, feeling anxious, defensive and under attack. Just before the meeting, Mr. S called to cancel saying he wanted to grieve and to put his wife’s devastating illness behind him. I left for a sabbatical. While I was away, I had an epiphany. I realized that this daughter was feeling anguish about whether she had been a strong enough advocate for her mother. I knew that, because she had had so much trouble giving herself up to the process of her dying, she was never able to say goodbye to her mother. I understood what she was feeling. I had experienced such anguish around the time of my own father’s death. My anger at her disappeared and my compassion reawakened.

So here is my fourth celebration hope for you: that you learn early that you can cure sometimes, heal often and care always. There is no medical remedy for the inevitability of death. So do your best and be compassionate with yourselves when things don’t go as well as you hope.

Reflect

Don’t get me wrong - medicine is filled with opportunities for joy. In fact, I can’t think of too many activities that are more fun than using your head, heart and hands to help someone feel better. And on top of that, if you care about your patients they appreciate you! And you’ll get paid for it! If you choose to do primary care, and I hope many of you will, patients will share their lives with you - births, graduations, weddings, divorces, promotions, book recommendations, home-made treats, photos… you name it. Some of you will see entire families of patients - grandma, grandpa, mom, dad, their siblings, the kids and their kids. You will find yourself holding entire villages of relatives in your minds’ eye. You’ll laugh and you may cry with them in the sanctity of your office or exam room. You’ll hold their secrets in confidence. The rewards are great and often unexpected… a bowl of home-grown plump red tomatoes; a child’s crayon drawing, a patient with chronic viral hepatitis who finally stops drinking (“Why now?” I asked after years of gentle probing. “Because you told me to,” came his ready reply); and you may just make a diagnosis, do a procedure or provide a treatment that saves a patient’s life. What can beat that as a source of joy!

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'You will encounter many things that will conspire to diminish your joy, your curiosity, empathy and compassion.'[/module]

Still, I want to give you a heads up – you will encounter many things that will conspire to diminish your joy, your curiosity, empathy and compassion along your journey. And there have been plenty of studies showing that this occurs. Some of these impediments are developmental and to be expected. Early on, you will be caught up in mastering the sheer volume of information you will need to know to be an effective clinician or a successful researcher. Buckle down and study as I know you have in the past. The foundation you lay now will stand you in good stead, I guarantee it. There will also be impediments that will seem beyond your control: too little time to pay close attention to the patient’s needs, too many patients to see, multiple hand-offs of patients’ care among various team members so you can’t really get to know the patients well. There are electronic records that do wonders for population management but divert our attention from the singular patient in the exam room; they steer our patients’ histories into prefabricated templates rather than representations of the patient’s narrative; they draw our eye contact away from the patient so that we miss the glistening tear in her eyes. You will very likely hear the dialect of the culture of medicine; “Go see the chest pain in room 2.” You will see tests being substituted for physical diagnosis and the magic that happens when a patient feels the expert, gentle, probing touch of a skillful physician. You will feel pressured to order tests or treatments that aren’t necessary because their availability drives demand in the absence of evidence about their efficacy. Often we stop seeing and questioning because we see through the lens of the culture of medicine that shapes these very practices.

So here is my fifth and final celebration hope for all of you. That you will take time to reflect, to stop and ask yourselves, am I acting with compassion and integrity in the best interests of this patient before me? Do I know enough about this particular, unique patient as well as the medical literature to make this judgment? Am I integrating my own professional expertise with the expertise of the patient? The expertise that only this patient can bring to me about the experience that is her life with all of its richness and complexity?

If you can say to yourself: Yes, I am doing my best to sustain my wonder, curiosity, tenderness and respect for those who have trusted me with their care; yes, I do care enough to ask and to really listen; yes, I am trying to seek balance and equanimity; yes, I am trying to be compassionate with myself when things don’t go well; yes I am taking time to stop and to reflect, to ask myself if I’m acting with compassion and integrity in the best interests of the patient before me….if you can say, yes, I am doing my best, then you will do honor to the privilege of being a doctor. And you can wear your white coats with pride.

This program aired on September 17, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.