Advertisement

Can My Company's Wellness Program Really Ask Me To Do That?

I wouldn't dream of finding fault with many typical wellness offerings: Quit-smoking programs, on-site gyms, more appealing cafeteria salads. Good for worker, good for employer, everybody's happy. But consider this email I received from an employee at a major national retailer:

Carey,

I see you’ve written several articles about the new health insurance laws, etc. The company I work for has [a major national insurer]. Last year we received a $25 discount bi-weekly if we filled out a health questionnaire, which of course everyone felt compelled to do as that would be a savings of $650 per year. Most people I spoke to felt uneasy doing it, as they felt it would lead to other invasive practices. Well, sure enough, this year, if you DON’T smoke cigarettes you get $10 off bi-weekly, but to get the additional $25 not only do you have to fill out a questionnaire, but everyone employed [here] (and taking the health insurance) has to have a screening which involves:

1. Waistline measurement

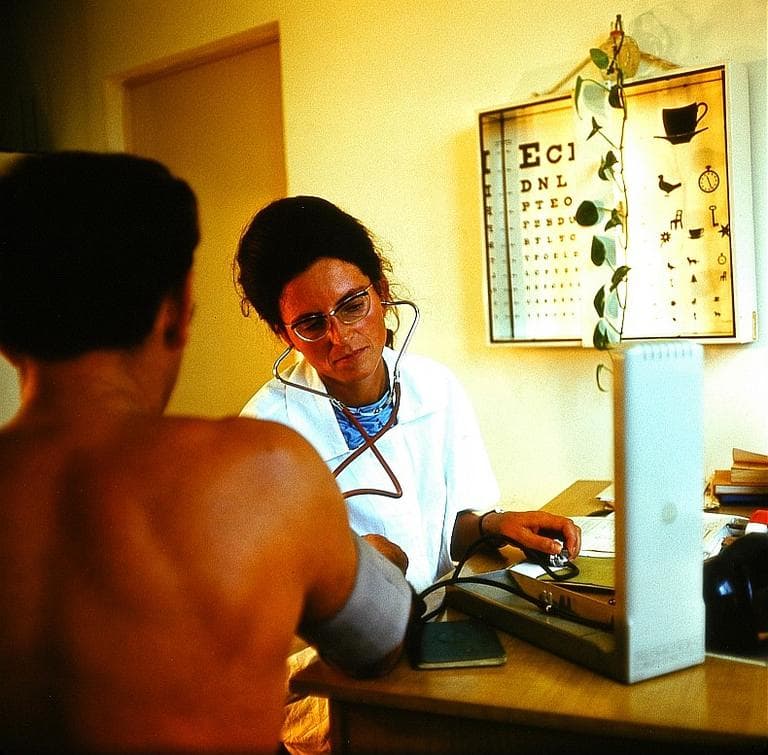

2. Blood pressure measurement

3. Blood draw to test for glucose, HDL and triglyceride levels.

If you do not pass these tests, you will lose your $25 if these are not brought down to an acceptable level by August (when we will be tested again).

Needless to say, this really shook a lot of people up, as it is so invasive, and is this even legal?

Would love to hear your thoughts on this.

Let's cut to the chase. Yes, it's legal. And it's a huge trend that began with only "carrots" — discounts on gym memberships, fun health fairs — and is now progressing to sticks. Or at least, to carrots that can feel a whole lot like sticks.

There are some important limits on what your company's wellness program can do. More on that soon. But here's the bottom line: Under federal law, your employer can vary your health insurance premium by up to 20 percent based on a "health factor;" that goes up to 30% as of 2014 and the government could eventually raise it as high as 50%.

[module align="left" width="half" type="pull-quote"]

Why should you foot the bill for all your Marlboro-packing, Miller-cracking, Big-Mac-chomping co-workers?

[/module]Readers, what do you think? On the one hand, if you're a fit, non-smoking, careful eater, why should you have to help foot the bill for all your Marlboro-packing, Miller-cracking, Big-Mac-chomping co-workers? An unhealthy lifestyle is known to be a major contributor to health care bills. and health costs have skyrocketed for years, sending premiums through the roof, hurting businesses and costing jobs. Any levers to bring them down must surely be tried.

On the other hand, there is clearly a potential yuck factor here. Having my employer measure my waist, or draw my blood??? Getting weighed and monitored in the workplace setting, or in the personnel filing cabinet, may not always be comfortable. What if my boss starts a "fun" pedometer contest among our company's departments and I'm the morbidly obese one? What about my medical privacy?

I asked the retail employee how people had responded to the wellness program. She replied:

I spoke to 3 people – all three are outraged.

The first person is refusing to have the tests – without giving too much info she has long term health issues and needless to say has huge out of pocket expenses as it is, but will sacrifice the $25 because she does not want any additional information on file other than what they already have.

The second person feels it is an invasion of privacy, but can’t afford to pass on the $25.

The 3rd person I asked also said she felt it was an invasion of privacy and is furious that we are being “forced” into doing this for the $650 per yr.

And on another note: we all work in the office and overall are paid on a higher level than a typical store associate (cashiers avg $9 per hr). To a store associate that $25 is HUGE.

And of course, $25 is only the beginning. If an average family pays close to $20,000 a year in health insurance premiums, and the health-factor differential could ultimately go up to 50% — you do the math. Kaiser Health News reports that already, among employees of the Swiss Village Retirement Community in Indiana, "Those who don’t smoke, aren’t obese and whose blood pressure and cholesterol fall below specific levels get to shave as much as $2,000 off their annual health insurance deductible."

So what are your rights? Here are the basics, courtesy of Patricia Moran, an employee benefits law expert at Mintz Levin.

The general rule: Federal law generally prohibits plans from charging different premiums to different employees based on a health factor. However, there is an exception for “bona fide wellness” programs. These programs allow an employer to vary premiums up to 20% based on a health factor (such as cholesterol, weight, smoking) but only if the employer offers a reasonable alternative to those for whom it is unreasonably difficult to meet the standard.

For example, let’s say the standard is a cholesterol count of 200. If an employee is below 200, he/she gets the better premium. This is okay so long as the employer offers an alternative standard to employees who are above 200. For example, take a cholesterol drug or attend nutrition classes.

Voluntary programs available to all outside of the medical plan are generally okay – for example, a gym discount, or a reward for attending a health fair.

Health Risk Assessments [like measurement of blood pressure and waist circumference] are sort of a legal land mine under the Americans with Disability Act and GINA [which protects genetic privacy], but it depends on what is asked and what it is used for.

An alphabet soup of other federal laws are at play here along with GINA and the ADA: HIPAA, which protects medical privacy, and ERISA, which governs employer health plans. I asked David Wilson, a partner at Hirsch Roberts Weinstein and an expert on wellness law, to parse all the legalese into a few principles that might be most useful to employees. He offered these points to remember about wellness programs:

Incentives, not penalties: A wellness plan is legal if it creates incentives for participation instead of penalizing an employee for not participating. A wellness program is considered voluntary as long as an employer neither requires participation nor penalizes employees who do not participate.

Avoid specific standards: To comply with the ADA, both voluntary and mandatory wellness programs should refrain from requiring the employee to achieve any specific health standard. The law bans discrimination based on health factors like health status, genetic information, medical condition, medical history and disability. An example of an impermissible health plan is one that gives a 20% premium discount for employees participating in the wellness plan with a cholesterol level under 200.

But the plan can use standards if...The reward is (for now) less than 20% of the total cost of coverage. The wellness program is "reasonably designed" to promote health. It gives employees a chance to qualify for the reward at least once a year. It allows a "reasonable alternative standard" to anybody for whom it is unreasonably difficult due to a medical condition, or medically inadvisable, to satisfy the initial standard. The employer may also choose to waive the standard for an employee who shows good cause. And it discloses that alternative standard in all wellness materials.

When it's mandatory: Employers may also have a mandatory wellness plan under certain circumstances. A mandatory plan cannot request family medical information or genetic information. If a mandatory program requires an employee to achieve a certain health standard, that standard should account for and be adjusted for age.

"The way to think about these things is that you can't use a stick, you have to use a carrot," Wilson said. "Employers can't use penalties but they can use incentives." And from the worker's point of view, you should get the reward "If you meet the goal or if you try to meet the goal."

And if I think my company is violating these rules? Ideally, he said, I would go to the director of my company's Human Resources department, who should be "the gatekeeper of fairness.” If I don't get satisfaction, I can either consult with a lawyer or file a complaint with a government agency.

If I think I've been discriminated against based on a "protected characteristic," such as age or genetics, I can file a claim at the Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination or the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. They would then send the complaint to my employer for a written response.

If my complaint is based on ERISA or HIPAA, those are federal laws and I could sue in federal court. Also, Patricia Moran noted, if I think the company’s plan discriminates under ERISA, I can call the Employee Benefits Security Administration for help.

Smart Ways To Wellness

In an ideal world, of course, I'd be so raring to get healthier that nothing my company's wellness plan did would bother me. That's the ideal for the wellness programs, too: To help me develop a long-lasting, sincere desire to get healthier. The catchword in the fledgling field of wellness research is "intrinsic motivation," and the data suggest it's the best way to go.

In contrast, financial rewards like the national retailer's $25 outcome-based incentive discount are "extrinsic," said Anne Marie Ludovici, director of wellness at Tufts Health Plan and a leading author and consultant on the topic. People who are not ready to change but suddenly face a major financial push like that may "dig their heels in further," she said. And incentives that backfire could reduce employee job satisfaction and engagement.

Yet, she said, it's becoming typical for large brokers and employers to add progressive requirements to wellness programs, going from simple questionnaires in the first year, to physical tests in the second, to required outcomes such as being tobacco-free or thinner in the third.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'If you’re a high-risk driver you’re going to have to pay more in premiums.'[/module]

The problem: "Even though you're saying that you’re giving discounts, people see it as being penalized," she said. "So it is very controversial. That's called 'outcomes-based incentives,' and I would never encourage a client to start with that, because it’s definitely very controversial and may not be very well received."

What's a better way? How the whole issue is framed is very important, Ludovici said. The company can explain that it's putting its faith in its workers, counting on them to try to get healthier even though the company won't see immediately lower health insurance costs. It can use its wellness program to help give employees the sense that they're cared about, she said, and working in a good place oriented toward high performance.

She, herself, has been known to use a car-insurance analogy: "If you're a high-risk driver you're going to have to pay more in premiums. And I think the industry is driving — excuse the pun — in that direction. If you want to eat triple cheeseburgers every day, go ahead, but you'll pay more."

Mari Ryan of AdvancingWellness, chair of the board of directors of the new Worksite Wellness Council of Massachusetts, says similarly that she would recommend starting a wellness program by first explaining to employees how their health is important both to them and to the whole company. "Self-care" can be a company value.

She would never advise going right to a "standards-based" program that offers rewards for reaching health goals; rather, she said, she would focus on creating a supportive environment: through, say, smoking policies and smoking cessation programs, or putting healthier food in vending machines.

Anne Marie Ludovici says that she sees the key as "engagement" rather than accountability. "Our philosophy at Tufts is we try to keep people engaged in health coaching if they need it," she said, "and keep them engaged in the behavioral change programs that will result in those improved outcomes. That feels right to me. I ran the governor's initiative in Rhode Island, and I saw that what was really getting people excited was being part of a healthy culture where employees thrive and feel this is a great place to work. And focusing on outcomes could really defeat that whole purpose."

Readers, please weigh in. How do you feel about your company's wellness program?

Further reading:

• Harvard School of Public Health researchers lay out the legal landscape of wellness programs in The New England Journal of Medicine here.

• Also in the New England Journal: Lessons from behavioral economics on how to design more effective wellness programs.

• A report on wellness programs by the Massachusetts Office of Consumer Affairs and Business Regulation.

This program aired on September 28, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.