Advertisement

Two Guys Walk Into A Bar And A Free Fitness 'Movement' Is Born

November. Waning light, biting winds. Toasty beds that say, "No, don't get up. Five more minutes."

It was just about a year ago that Bojan (pronounced Boyan) Mandaric and Brogan Graham faced the November problem head-on over a couple of beers at a Boston pub.

Back when they were rowing buddies on the Northeastern University crew team, they knew they had to get up to work out or else they'd let down the rest of the boat. But now they were grown-ups, thirtyish, with real jobs and long workdays, and no teammates depending on them. Every fall and winter, their fitness slid.

As Bojan recalls it, he asked Brogan something like, “Dude, do you want to help me get my ass out of bed starting November first?' And Brogan said, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’”

So they started to meet up at 6:30 on Monday, Wednesday and Friday mornings, “running stadiums” — bounding up the concrete seats — or steep hills, throwing in push-ups or burpees. Just the two of them, tracking their progress on a Google doc labeled "November Project."

Many an idea born in a cozy bar later dies in the cold light of day, but this one worked through the winter, and in May, Bojan said, they decided to “open it up a bit. Throw out a few tweets." Plus post a blog and a Facebook page.

These days, when Bojan and Brogan work out, a couple-three hundred people do it with them.

They call themselves a “grassroots morning fitness tribe,” only unlike most tribes, anyone can join. You just have to show up. And unlike most fitness programs, the November Project is completely free, and its founders pledge it will remain free forever.

Advertisement

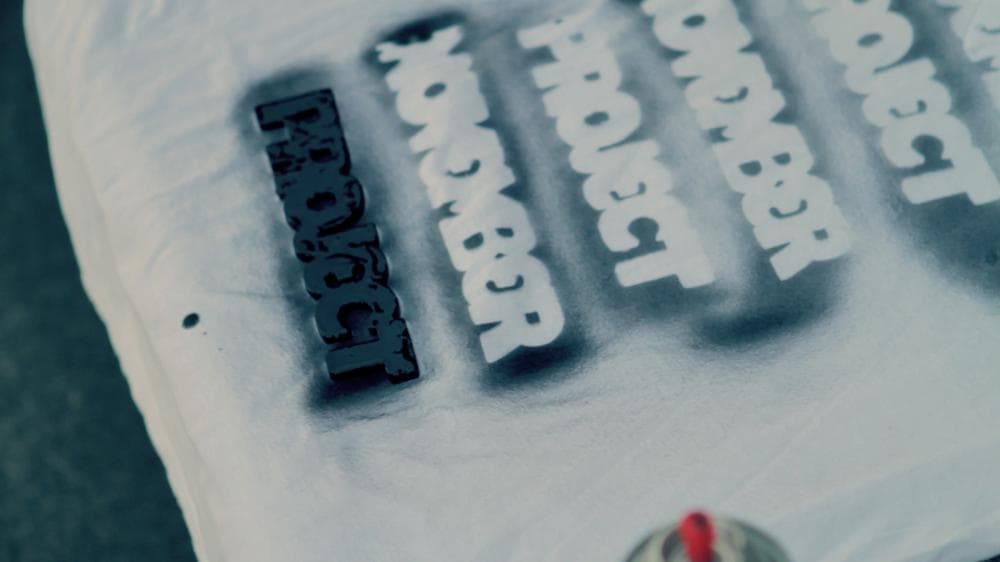

It is not just a tribe but a movement, they say, a demonstration that social connection is an incredibly powerful fitness tool, and if you build it, they will come. When attendance recently hit 300 at a single workout, Brogan and Bojan decided to celebrate with new ink: a November Project arm tattoo, showing a clock at 6:30.

The group creates some striking new Boston sights. On Fridays, its 200-strong members come charging over the steepest hill in suburban Brookline like some save-the-day cavalry in fluorescent running shoes. On Wednesday mornings, they brave the brutal high steps of the Harvard stadium. Mondays, they turn flash mob and meet in variable locations tweeted in advance, from the Museum of Fine Arts to a Charles River canoe dock. All the workouts are "scalable," doable at varying levels for elite athletes and newbies alike.

So is this the start of another Boston-based revolution? Will it spread?

The model could likely work elsewhere where population is dense, said Prof. Gary Liguori, head of the Health and Human Performance Department at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga and an on-call expert for the American College of Sports Medicine.

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]'This is interesting how it just continues to grow, and people want to be a part of it.'[/module]

"I've heard of nothing else this size," he said. "Running clubs have been around forever, and break up into small groups who go and do their things. But this is interesting how it just continues to grow, and people want to be a part of it."

The November Project fits into a major recent trend, he said, toward 'outside-the-gym routines," often using little or no equipment.

Think boot camps and outdoor parcourses. In fact, The American College of Sports Medicine reported this week that for the first time, "body weight training" turned up as an emerging trend in its annual fitness survey.

Though part of a trend, Gary said, the November Project also appears to be on the cutting edge in its use of social media to motivate. Though some exercise apps try to connect users, the fitness field has generally tended to lag a bit on using using social media to promote physical activity, he said.

"We use the traditional paradigms to try to get people to exercise — certain days a week and this particular exercise and letting the government recommendations guide us," he said. "There's nothing wrong with those, but it doesn't capture people. But when you drive down a street and see all these crazy people running up a hill, you might say, 'Hey, I want to try that.'

The November Project clearly draws major impetus from its founders' high-energy personalities, he added, but social media may allow even less-outgoing people to form similar groups for other niches. Because clearly, he said, the November Project is a niche, not for everyone: Not for people who hate group exercise, or morning workouts, or the cold, or competition. And many people can't or don't want to work out as intensely as the November Project norm.

Indeed, like any tribe, this one has a culture: They are "weatherproof," so even the winds and rains on the cusp of Sandy last Monday morning were seen as no excuse for a no-show.

Spirits can get so high they need profanity for full expression, often a congratulatory "F***, yeah!"

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"] 'Constant high fives, hugs before and after workouts'[/module]

And the general spirit is shockingly upbeat for early morning and overwhelmingly supportive, even for the hard-core who compete by posting their performance stats on the project's blog.

'There’s constant motivation, there’s constant high fives, hugs before and after workouts," Bojan said. "It’s like nothing else that we know of."

At a recent stadium workout, I asked a few huffing stair-climbers at the end of the workout why they came.

"I come for the high fives," said one. "It makes me feel awesome," said another.

"It brings that competitive edge to working out," said Devin Lehman. "If would be so boring by yourself — no one's pushing you, and it's like now there's a couple of hundred people pushing you."

"It's about community," said Jake Minkoff, who couldn't work out because he was nursing an injury but showed up anyway. "What we're all about is making commitments and sticking to them. You're far less likely to bail on your workout if you know you have a bunch of people counting on you and expecting to see you there."

People do compete, he said, "but it's more a competition against yourself — people want to do better than they did last week or last month."

A personal note: The November Project is gaining ever more buzz lately: Boston Magazine just posted a piece on its one-year anniversary here. But I stumbled upon it by accident one morning in August, when I suddenly found a couple of hundred fit young people on my usual hill run, most of them much, much faster than I was.

I can't logistically do the November Project thing whole-hog, but Friday mornings on the hill have become a special treat. I try harder because of the inspiring runners around me, and where else can you find a crowd of happy smiling people before 7 a.m.?

How big, I asked Bojan, might this thing get?

"As big as Harvard stadium allows," he said. Then, "I hope it will start opening locations around the country. How big is it going to get? I have no idea..."

This program aired on November 2, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.