Advertisement

Back To The Future: The ICA Rewrites The History Of 1980s Art

Nostalgia for the 1980s seems to be everywhere—from American Apparel fashion to 8-bit computer graphics, from Ronald Reagan worship to plans for new “Star Wars” films. But the decade has been a blindspot for the art world. Sure, art stars from the decade like Cindy Sherman, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Barbara Kruger get retrospectives. But broad reconsiderations of the era’s art are rare. It’s like the art world would like to forget it happened—particularly the splashy macho bombast of 1980s painting stars like Julian Schnabel.

“This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s” at the Institute of Contemporary Art (100 Northern Ave., Boston, through March 3) is a landmark revisionist history of art of the preppy, greed-is-good, Reagan-Thatcher era. Instead of the standard ‘80s art history of post-modernism, neo-expressionism, and culture wars, ICA chief curator Helen Molesworth rounds up nearly 100 artists—mainly from New York and Los Angeles—for a requiem.

“This Will Have Been” is a political show, from a decidedly liberal perspective. The exhibit critiques ‘80s economics and touches very slightly on the Cold War, but primarily Molesworth reframes the ‘80s through two lenses: feminism and the AIDS crisis. She recounts how feminist gains of the 1960s and ‘70s collided with the decade’s ascendant conservatism. She tells how activists demanded help for AIDS victims even as American political and religious leaders ignored or demonized the dying and hampered medical responses. And in these things, Molesworth implies, lay the roots of today’s Tea Party, wars, Great Recession, and gay activism.

“For many people, the 1980s are the definitive end of the 1960s,” Molesworth said at a press preview. But at the same time, she asserted, “This is really a moment when artists felt what they did matters.”

Perhaps the most iconic artwork of the decade is Jeff Koons’s 1986 “Rabbit,” a dimestore inflatable plastic Easter bunny exactingly reproduced in stainless steel. Its mirrored surface dazzlingly reflects us and everything else around it. It’s both mirror-mirror-on-the-wall and mercury skinned “Terminator 2.” It symbolizes a crass 1980s yuppie nouveau riche, but also challenges high-class taste by taking a beloved tacky middle class knickknack, reproducing it in expensive materials, and elevating this post-modern copy into the fine art world.

Molesworth’s other icon of the decade is actor-become-President Reagan, who here embodies the decade’s rightward shift, its consumerism, its merging of high and pop culture. Hans Haacke’s 1982 installation “Oil Painting: Homage to Marcel Broodthaers” presents a gold-framed oil portrait of Reagan, looking pinched and skeptical, hanging on a red wall behind a red velvet rope, like a shrine honoring a Soviet premier. On a wall opposite it is a giant enlargement of a photo of a protest march through New York advocating nuclear disarmament. A red carpet runs between the two images, inviting us to choose between a Cold War “great man” and the “people,” but Haacke leaves his own position ambiguous.

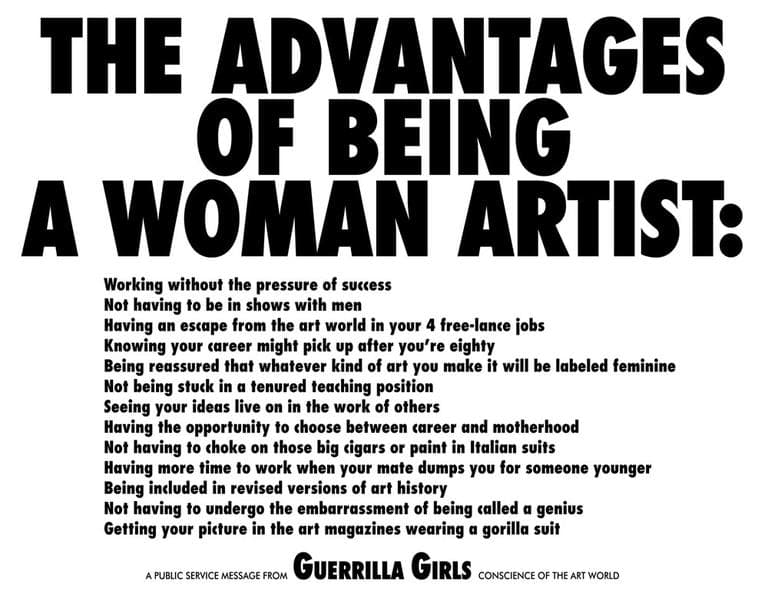

Ultimately this is a show about people demanding rights, pursuing, as Molesworth writes, “an expanded idea of freedom” via the civil rights movement, gay activism and feminism. These demands challenged traditional male American domains (including art) as well as the very notion of masculinity (see: gay men, butch women, straight guys going emo). A wiseass 1988 broadside by the anonymous feminist collective the Guerrilla Girls identifies several “Advantages of Being a Woman Artist”: “Working without the pressure of success,” “Not being stuck in a tenured teaching position,” “Being included in revised versions of art history.”

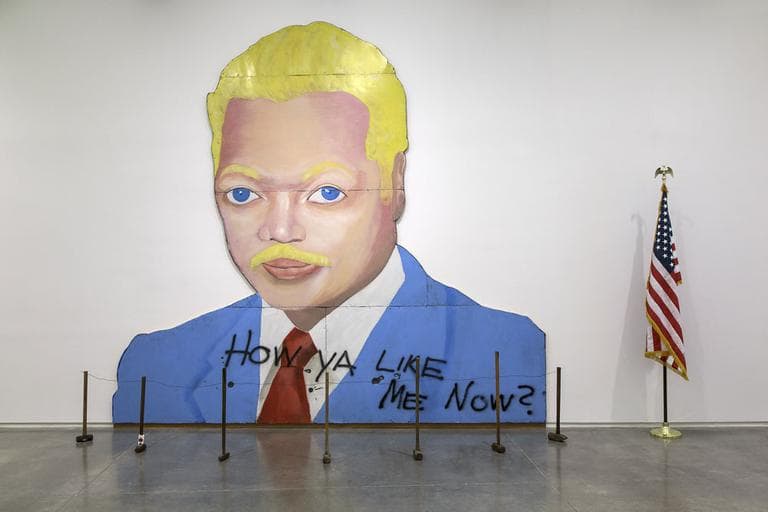

David Hammons’s 1988 billboard-sized portrait of Jesse Jackson, the African-American civil rights activist and 1984 and ’88 Democratic presidential candidate, turns him caucasian, blonde and blue-eyed. The title, “How Ya Like Me Now?” (from the title of Kool Moe Dee’s 1987 rap) is scrawled across the painting’s bottom—defiantly questioning how race colors people’s opinions.

A black and white photo from around 1980 by Robert Mapplethorpe shows the midsection of an African-American man in a neat polyester suit—with his penis hanging out. Molesworth includes it as a representation of gay desire, but for conservatives Mapplethorpe’s work exemplified artistic immorality and indecency that they sought to stop by reducing federal grants to individual artists and challenging exhibits of the art.

Mapplethorpe, a New Yorker, died of AIDS in a Boston hospital in 1989. AIDS deaths had topped 16,000 in America by 1986. The perception that AIDS was a “gay disease” enabled a homophobic federal government to, generally, turn a blind eye toward the devastation. The death toll more than doubled in 1987—when President Reagan first commented publicly on the disease.

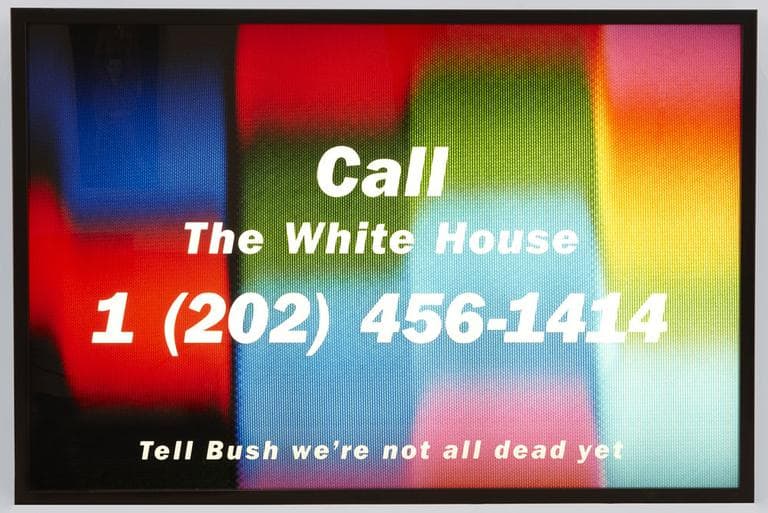

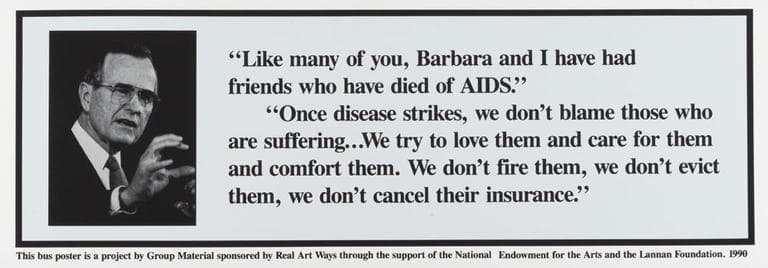

“Kissing doesn’t kill: Greed and indifference do” reads a 1989 bus poster by Gran Fury, an offshoot of the AIDS activist group ACT UP, featuring photos of couples of mixed races and sexuality. “Call the White House,” Gran Fury member Donald Moffett’s 1990 lightbox sign reads, “Tell Bush we’re not all dead yet.”

The show concludes with Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled (Perfect Lovers)” (1987-1990), a pair of identical office clocks that are set to the same time and slowly, eventually tick increasingly out of synch. A member of activist art collective Group Material but also, in his own work, a pioneer of kinder, gentler neo-Conceptualism and Minimalism, Gonzalez-Torres intended the clocks to be a portrait of himself and his lover, Ross Laycock. In retrospect, the clocks a bittersweet memorial to loss and separation. Laycock died of AIDS in 1991. Gonzalez-Torres himself succumbed to the disease in 1996.

In “This Will Have Been,” Molesworth ambitiously attempts to redefine a whole decade—and in doing so catapults the ICA onto the map nationally as a place where history gets written. Molesworth’s art of the ‘80s is often cool, drab and ironic—even when the issues are hot. Her approach is radically subjective and personal. Which itself is an outgrowth of ‘80s feminist and queer approaches. She eschews chronology in favor of themes. She discards the decade’s standard art history, but also omits or minimizes many other major creative developments—graffiti, Maya Lin’s “Vietnam Veterans Memorial,” Andres Serrano’s notorious 1987 “Piss Christ” photo of a crucifix submerged in urine, MTV, video games, and the rise of “alternative” art comics ranging from Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” to Matt Groening’s “The Simpsons.” In fact, Molesworth’s version of 1980s art is so boiled down that it prompts the question: Does a major museum telling the history of a decade have a responsibility to be more expansive?

This program aired on November 26, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.