Advertisement

When The Full Sticker Shock Of Health Coverage Hits Our Family

As the new state Health Policy Commission begins its work to bring down health care costs, here's one Massachusetts family's reminder of why the issue is so urgent. The excruciatingly high prices of both insurance and care mean that some must choose between health insurance and a new furnace, or health insurance and a car. This is not an abstract policy issue; it is a daily burden with major effects. One mother's story:

By Sara Cushing

Guest contributor

A few weeks ago I resigned from my job as a project manager at one of the largest health care delivery systems in the United States. I have worked in different capacities in the health care industry in the Boston area for the last eleven years, but decided to leave my career because I wanted a change — to follow my dream of becoming a writer.

Many things needed to be considered about such a family-life-altering decision, including one that hadn’t been a concern of mine in the past: what my family’s next steps would be in purchasing health insurance. I have always carried the health insurance — a very robust PPO (“paid provider option”) family plan that was largely subsidized by my employer.

The direct cost to me (paid bi-weekly on a pre-tax basis) was roughly $400 a month. In discussing my career departure with my husband, we knew that the monthly cost for a similar plan purchased through the Health Connector (the Massachusetts state agency that acts as a vehicle to allow uninsured residents to purchase health insurance through local health insurance companies) would likely be higher. Much higher.

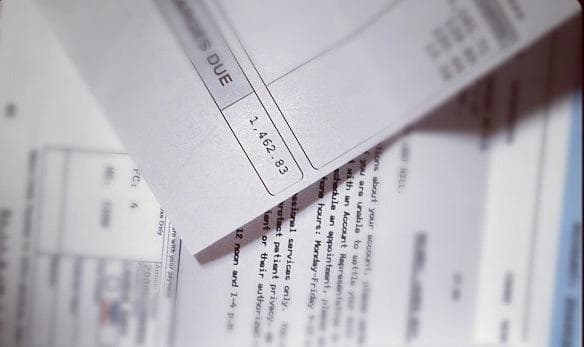

Try something closer to $1700. About the same as our monthly mortgage. About half of what my take-home pay used to be — money that was no longer coming in. And we see no way around it.

Because my husband is in a higher income bracket we’re not eligible for subsidized coverage though the state; and because my husband is a contract employee, his employer doesn’t provide subsidized health care coverage.

This means that we’re looking at the same cost for a family plan whether we buy through his employer; the Health Connector; or through my employer’s COBRA plan (which allows me to purchase the same health care coverage as offered by my employer for up to 18 months after ending employment, though I am responsible for 102% of the cost — the additional 2% is for administrative fees).

I live in Massachusetts, where legislation was passed a few years ago mandating health care coverage for all residents. The legislation helped to create the Health Connector agency so that people could purchase health insurance in larger risk-pools instead of directly from health insurance companies, to allow for more competitive pricing and coverage options for individuals and families.

This all sounds great, right? What many people do not understand, however, is just how steep the monthly premium cost gets, just how painful a $1700 bite out of a family budget can be.

Of course there are other plans offered through the Health Connector that have less expensive monthly premiums (for example, $1000/month for a family plan) but these plans have higher co-pays (the flat dollar amount that you would pay for an office visit, for example); coinsurances (usually a percentage of the cost for an office visit); individual and/or family deductibles; and/or out-of-pocket maximums.

If not for my previous work in researching health insurance coverage for patients, I would have no idea what any of these words mean. A deductible is a monetary threshold that an individual (or family) is responsible for paying before their coverage kicks in. For example, if I (God forbid) have to go to the hospital for emergency surgery, I would be responsible for paying up to my individual deductible before my coverage kicks in to cover the rest. This deductible could be anywhere upwards of $2,000.

An out-of-pocket maximum is the annual maximum that I am responsible for paying for my care. For example, if (again, God forbid), my hospital admission required extensive surgery, treatment, or extended stay in the emergency room or intensive care unit, and I have a $10,000 out of pocket maximum, then I am only responsible for the first $10,000 in cost for my care and my health insurance will cover the remaining costs, if they’re determined to be medically necessary. So in the event of something catastrophic, I will pay $1,000/month in premiums and could accrue up to a $10,000 personal expense in the cost of my care.

A lot of the current political conversation about national health care coverage ignores the actual cost to the purchaser. I think that mandating coverage for all is a good thing and will help to initiate access to primary care and preventive health services. But if people can’t afford the monthly premiums and costs of care, what good does the mandated coverage offer for the people who have to pay for it?

My family – thankfully – is healthy and currently does not ‘consume’ a lot of healthcare services; our trips to the doctor are primarily for well-visits. To pay $1,000/month for services we might not even use means drastic cuts to our already pared-down lifestyle and budget: Do we sell one of our (two) cars to eliminate monthly expenses? What if our thirty-year old oil burner doesn’t survive this winter and needs to be replaced? How do we save? How will we continue to contribute to our son’s college tuition savings account?

[module align="right" width="half" type="pull-quote"]Families like mine have to evaluate the risk-benefit analysis of whether we can afford to pay steep monthly premiums in anticipation of worst-case scenarios or keep the roof over our heads.[/module]

It seems our only other option is not to purchase insurance and, instead, incur a tax penalty when we file our state taxes next spring. But this also means that we will then take our chances that we won’t need extensive health care services in the near future. And like many parents, this doesn’t sit well with my often overly responsible personality and family management style.

Mandating health care coverage through state or national legislation doesn’t mean that the cost of care is going to go down anytime soon to make a difference to the end consumer. Until the cost of care is managed, the cost of health insurance isn’t going to be eased. The industry movement away from fee-for-service payment models will directly impact the out-of-pocket cost to individuals and families – but again, not in the immediate future. And this central issue to those of us paying steep costs for coverage isn’t part of the political or news media conversations. It should be.

I fully appreciate the irony in my leaving a job that provided a health insurance benefit that was at a small cost to my family. But choosing a new career path – one with different benefits, like flexible time to take care of my son and the fulfillment of doing something that I love – shouldn’t present my family with such a financial dilemma. Until the cost of providing care becomes better managed, families like mine will continue to have to evaluate the risk-benefit analysis of whether we can afford to pay steep monthly premiums in anticipation of worst-case scenarios or keep the roof over our heads.

Sara Cushing is a freelance writer. She lives with her family on Cape Cod.

This program aired on November 26, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.