Advertisement

The View From The Top Of The World: A New Book On Inuit Art

The 1950s and ‘60s were a time of major change for the Inuit of the Canadian Arctic.

“People were more and more moving from their nomadic camp lifestyles into communities,” explains Maija Lutz, the author of a new book, “Hunters, Carvers, and Collectors: The Chauncey C. Nash Collection of Inuit Art.” She speaks and sign copies of the book at Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 11 Divinity Ave., Cambridge, at 5 p.m. Wednesday, Dec. 5.

“These communities had been established by the Canadian government in response to the need for education and health services and various kinds of things,” Lutz says. “So people were beginning to get away from living totally off the land to more of a cash economy. As people were getting more and more into a cash economy they needed money.”

But how to earn it?

A Canadian artist by the name of James Houston, during a painting trip to northern Ontario in 1948, was offered a free plane ride to an Inuit settlement at what is now called Nunavik in Arctic Quebec. He was wowed by new Inuit carvings—often spare, raw stone works depicting Inuit life and spirituality. He began bringing Inuit art back to southern Canada, to Montreal, to sell. By 1957, he was living at Kinngait (Cape Dorset) on Baffin Island, where he served as a community economic development officer, Lutz says. And he made it his mission to foster contemporary Inuit art, in part to foster Inuit communities.

“Inuit people very unabashedly have said that, yes, they were making this art to make money, to make a living,” Lutz says. “For a lot of women, especially, this was life or death.”

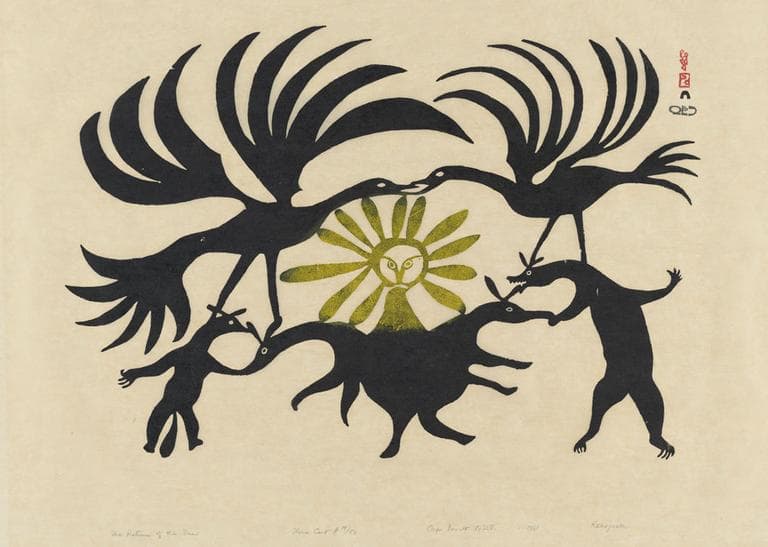

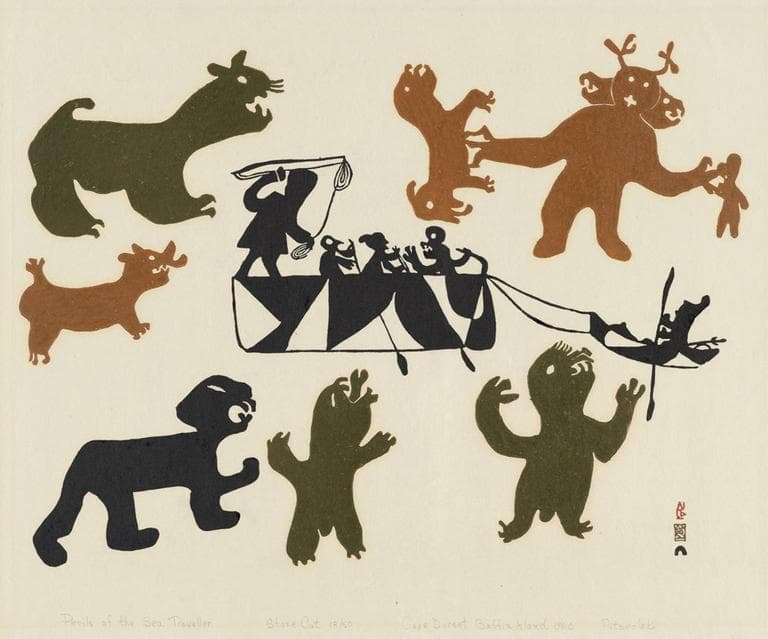

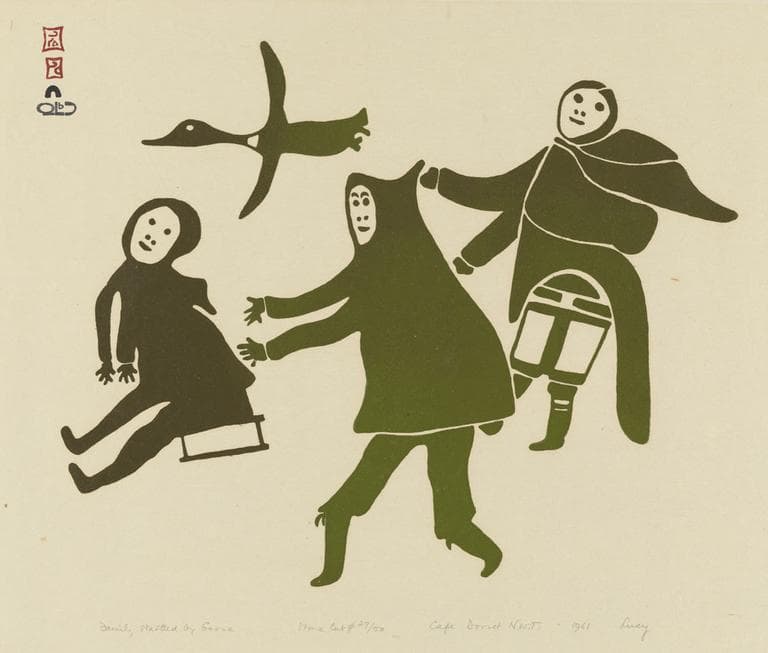

The Nash Collection, donated to Harvard in the 1960s, features sculptures and 60 prints that primarily represent the brilliant first flowering of the West Baffin Island Eskimo Co-operative, which Houston helped found in 1959 and which for many still defines Inuit art. (A small selection prints and stone sculptures depicting hunting and owls is on view in the Peabody Museum’s lobby.) Printing from carved stones encouraged a strikingly simplified, bold aesthetic.

“One of the artists, Kananginak Pootoogook, who just recently died, one of the people who was just instrumental in Inuit art from the very beginning, he said that what’s so important for him is that this work represents their culture that was so important to them, but that is eventually going to change,” Lutz says. “It’s like this documentation, a kind of picture of Inuit life and culture the way that it existed. And as long as this exists then it’s not going to be forgotten.”

Inuit art—particularly stone or bone carvings and animal hide works—had long been available to travelers to the Arctic. But Houston made two major changes. He helped introduce printmaking to Baffin Island’s Inuit. (A small group of Inuit men printed works that they made based on drawings submitted by people throughout the community.) He then promoted their work through the rest of Canada—and the world.

“Once he entered the Arctic and started bringing this art outside and exhibiting it,” Lutz says, “it just took off.”

In the 1970s, Lutz — now living in Warwick, Rhode Island, and the retired head of Harvard’s Tozzer Library — spent a winter on Baffin Island and then a season in Labrador studying indigenous music as part of her Ph.D. dissertation research.

“The landscape is just very awesome,” Lutz says. “It takes your breath away because there’s just this expanse of snow if you’re there in the winter.”

She found that traditional Inuit styles, like throat singing, had been supplanted by music and jigs and reels that had been introduced by 19th century whalers. And they, in turn, were being supplanted by rock and roll.

“Things had already changed a lot by the time I went up there,” Lutz says. “People weren’t using dog teams to go hunting. They were using snowmobiles to go hunting. They were living in three-bedroom prefabs. And airplanes were an important part of life.”

It was a time when it was widely felt that to enter the modern world, old ways of doing things had to be abandoned. Today, old traditions are being revived as people recognize that you don’t have to get rid of all the old to embrace the new—and they try to reclaim what was lost when they gave up the old ways.

“When I was on Baffin Island, I was really interested in the Inuit throat music,” Lutz says. “And people would sort of laugh and snicker and didn’t want to do it. Because I think they thought outsiders thought it was kind of silly. It has made a real comeback and now it’s being performed at all these festivals.”

This program aired on December 4, 2012. The audio for this program is not available.