Advertisement

Mickalene Thomas: The Seduction of Blackness

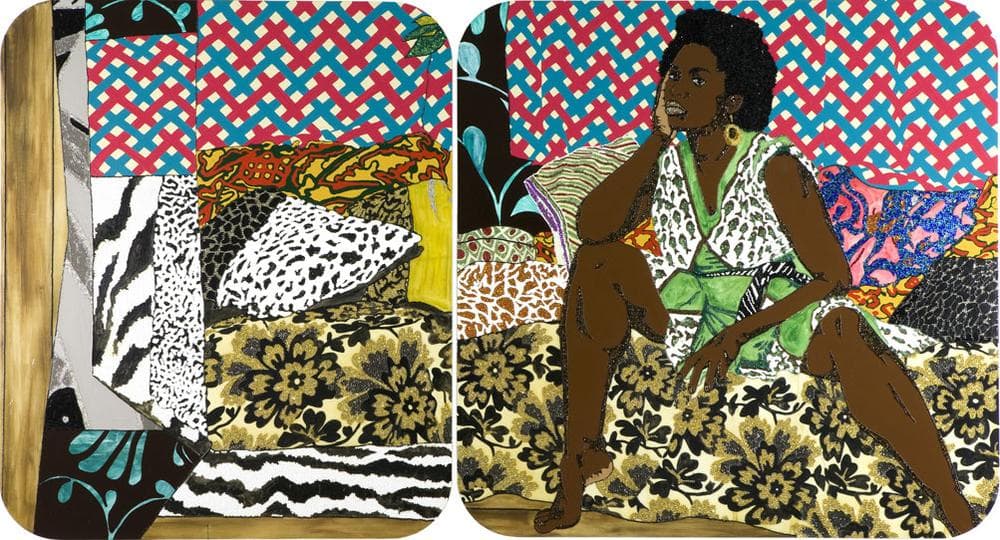

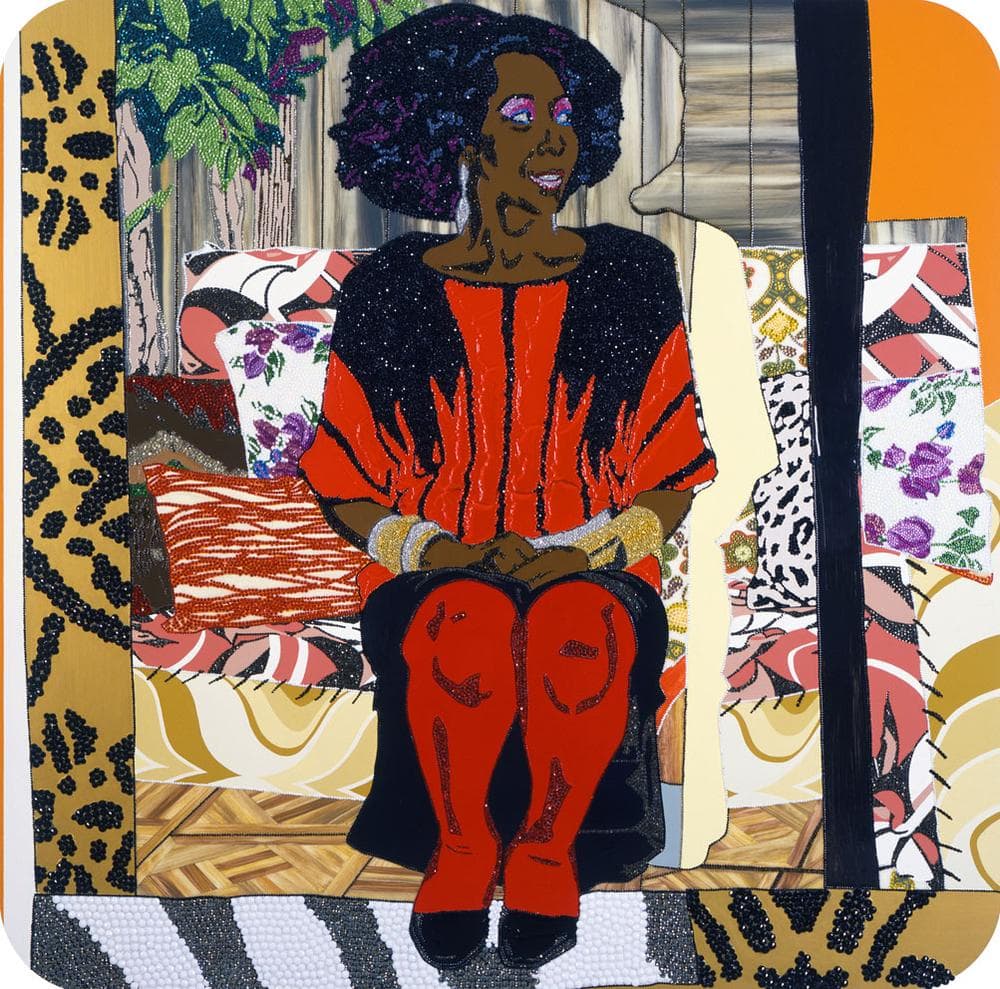

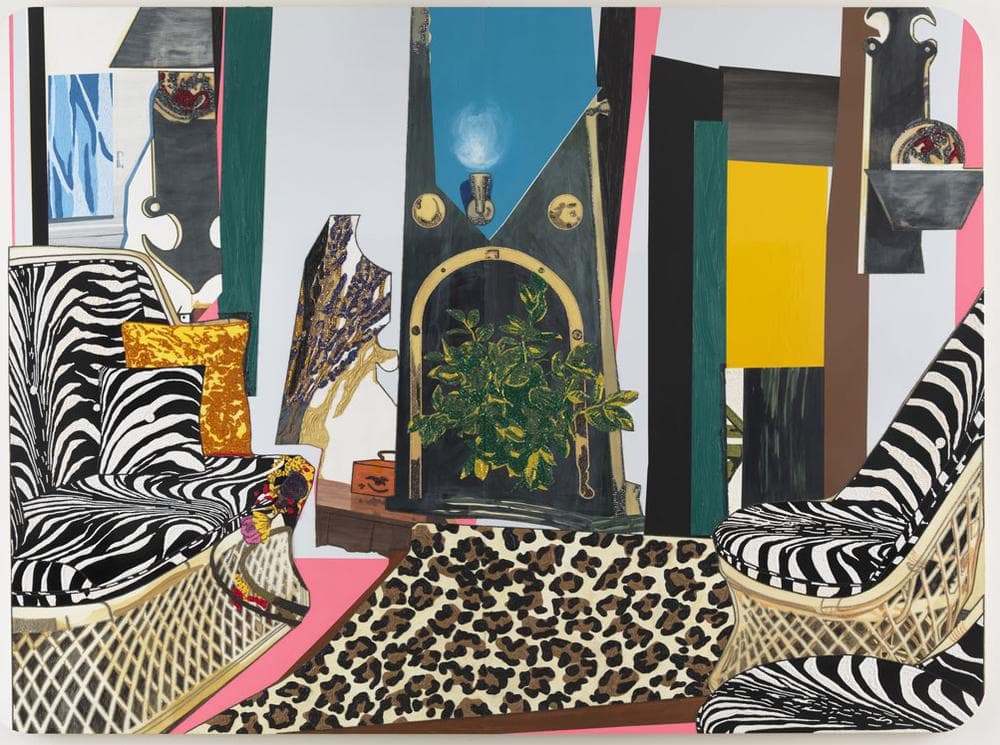

Over the past half decade, one of the hottest artists in New York has been Mickalene Thomas. Her rhinestone-encrusted paintings of black women in boldly patterned interiors that evoke the 1960s and ‘70s are the subject of a five-painting exhibit at the Institute of Contemporary Art (100 Northern Ave., Boston, through April 7) and a larger traveling show now on view at the Brooklyn Museum (through Jan. 20).

On Dec. 11 at the ICA, I spoke to her about her mom (a fashion model in her youth), everyday middle class African American women, and the intersection of black beauty and black power.

“So much of the beauty that I really try to capture and emulate in my own work stems from my mother," Thomas says.

“Growing up, my mother would walk into a room and her beauty was so powerful that she could get whatever she wanted from people—attention, conversation. People just wanted her energy. They wanted to be around her. No matter if she said something or not. I think beauty has a form of power. And then on top of a woman being beautiful that way, if she’s intelligent, then that’s a double. And that was my mother. And I always wanted to understand that. People didn’t look at me that way. I didn’t possess my mother’s beauty in that sense. She had that ideal beauty that you just wanted to know. You knew that woman when she was in the room. I’m just trying to understand the power of that beauty.”

“A lot of these women that I choose to sit and installations that I create and photograph and paint are usually women that I myself want to emulate.”

“For me, these women portray that sort of seduction that resides in a blackness. My intent is not to portray them in a stereotypical way but to portray the beauty and sexuality that I see from women that I surround myself with, from women that I grew up with. The sort of ‘Ebony,’ ‘Jet,’ ‘227’ woman (from the show) that everyday woman, that middle class black woman.”

“The late ‘60s and ‘70s for me is a particular space for black women and black people where they were really sort of defining themselves. Defining themselves and their place in the world culturally, artistically, how they feel about their own sense of identity. With mantras and slogans—‘We’re black and we’re proud.’ This forging their foundation, saying, ‘Look at us, we’re here, this is our validation.’”

“I was born in the ‘70s so by the time I was 9 years old it was 1980, so I was more a product of the ‘80s growing up. The ‘70s is sort of a blur to me. For me the nostalgia is sort of remembering these slight moments in the environments that I grew up in. I remember being in rooms and my family is sitting around the table having meetings and discussions about how they were no longer going to straighten their hair and what that meant. That meant that you were really sort of making some definite changes within yourself and your own world, even if that world was only within a few blocks. You were looking at yourself and you were accepting yourself. And that’s a scary place. That’s a huge risk for thousands of people to take this stance, to no longer want to conform to this particular ideology of beauty that was put upon them.”

Thomas’s Brooklyn Museum survey includes a documentary movie she made of her mother, Sandra Bush, who died Nov. 7 at age 61. “From [age] 59 to 61 you can tell physically she was really starting to change. And I took notice of that. And I was just curious of how she felt when she looked at herself in the mirror. What was that feeling? … She didn’t like what she saw. Because she didn’t look the same. She didn’t feel like she looked beautiful. I remember her saying that the one thing she hated about being sick was that it took her beauty away. Because that’s how she engaged with the world. And not that she didn’t think that her own intelligence could carry weight. Even though she looked different to herself, she was still very beautiful. People still thought she was exquisite and beautiful because of the way she carried herself. But she didn’t see herself that way. And it doesn’t matter what anyone thinks or how we see you. So I think that part of her also played a huge part in her sickness because once you allow yourself mentally to break down it adds a layer to your illness because your mind is very powerful.”

This program aired on January 3, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.