Advertisement

Guastavino’s Boston Library: Building A New Democratic Architecture

The old wing of the Boston Public Library’s Copley Square Branch, the 1895 McKim Building, represents one of the last great buildings of its breed. It arrived as construction of major buildings was shifting to steel. The metal allowed structures to span great distances under heavy loads, but to appear light and airy. So it became one of signature materials of modern architecture, birthing the towering skyscrapers and bridges of the past century and a half.

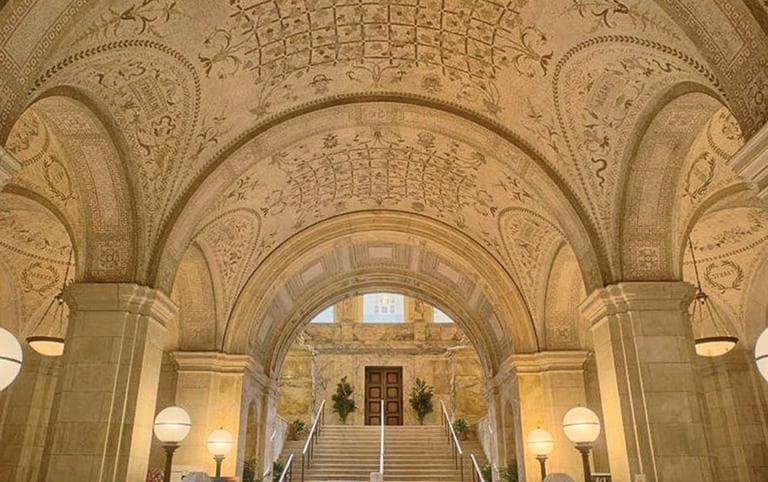

But the McKim Building rose at the turn of the 20th century, in an era of transition. Its designers signaled its cultural aspirations by looking back to old Europe for signature aspects of its design, particularly the dramatic vaulting seemingly woven out of ceramic tiles throughout the first floor.

This method and its maker are the focus of an illuminating architecture exhibit “Palaces for the People: Guastavino and America's Great Public Spaces,” organized by John Ochsendorf, a professor of architecture and engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, at the Boston Public Library’s Copley Square Branch (700 Boylston St., Boston, through Feb. 24). The building was Rafael Guastavino Sr.’s first major commission in the United States. Its success—the building is now a National Historic Landmark—powered the rest of his career.

A Spanish builder, Guastavino (1842–1908) emigrated from Barcelona to New York in 1881. He was experienced in designing and constructing traditional Mediterranean-style thin ceramic tile vaulting—self-supporting arches and vaults built from layers of interlocking terracotta tiles bonded by mortar. It’s an old technique that can be traced back through medieval Gothic cathedrals and ancient Roman temples. Guastavino made its affordability, light weight, strength, and—especially—resistance to fire modern selling points.

In the McKim Building (named for its architect, Charles Follen McKim of the New York firm McKim, Mead and White), Guastavino gives drama and grandeur to the building’s entrance lobby with sweeping rows of vaults, decorated with vine patterns. His style fit nicely into McKim’s overall Renaissance Revival plan. Underlining the institution’s proud democratic claim to being the first large free municipal library in the United States, the entrance space embodies the trustees’ and McKim’s notion of the library as a “palace for the people.”

Guastavino’s vaulting is more spare but still powerful in (what is now) the McKim building’s Map Room Café, the popular reading room, and the arcade surrounding the open air, Italian Renaissance-style courtyard. In the exhibit, Guastavino planning drawings for the Boston library sketch ceilings proposed for the courtyard arcade and a driveway.

Based in Boston and New York, Guastavino’s firm, led after his death by his son, would produce tile vaulting for more than 600 buildings in 36 states, including train stations, churches, and the Nebraska State Capital. They constructed some 60 projects in greater Boston—including vaults at the Massachusetts State House, Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Christian Science Church. (The firm patented its technique, which prevented much direct competition.)

The exhibit offers new photos of vaulting in Providence’s Central Congregational Church (the firm’s first dramatic dome), New York’s Ellis Island’s Registry Hall, the Oyster Bar in New York’s Grand Central Terminal, and the City Hall subway stop in New York. The firm did work at the Bronx Zoo and the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. (a dome supported by hidden flying buttresses, a medieval technique).

Even as Guastavino was at work on the Boston library, his Old World methods were already being supplanted by the steel supporting skeletons of the first skyscrapers, which would soar ever higher while seeming less and less bound by the laws of gravity. Guastavino’s vaulting, however, is all about weight. Its feeling of mass gave modern American civic architecture a stateliness and gravitas that still signals the importance of the democratic business going on inside.

Earlier:

This program aired on January 10, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.