Advertisement

Mayor Menino Leaves A Lasting Legacy In The Arts

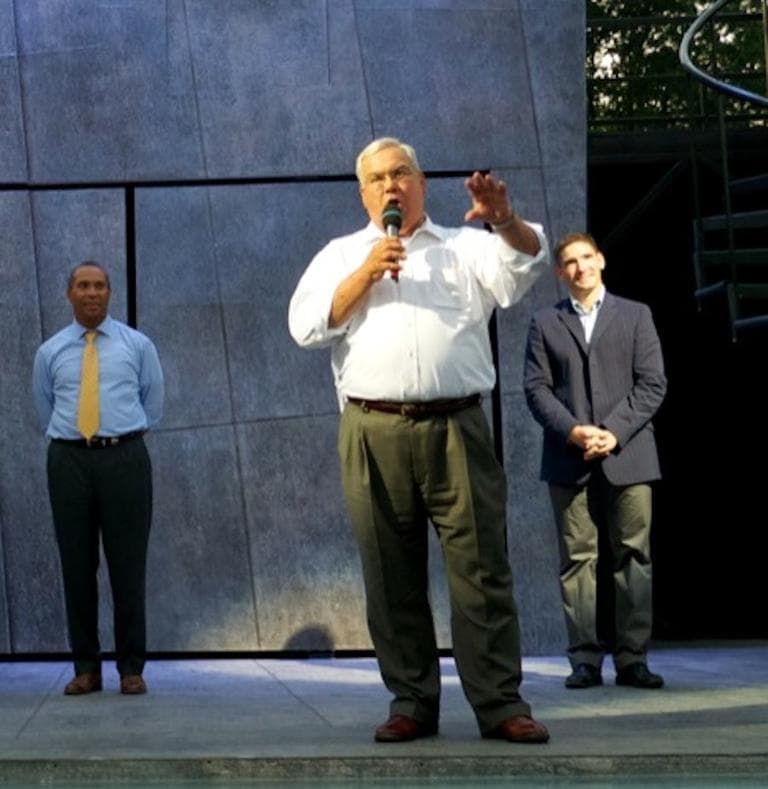

The Boston Theater Critics Association kicked off its annual Elliot Norton Awards ceremony earlier this month with a special tribute to Boston Mayor Thomas M. Menino. Commonwealth Shakespeare Company is dedicating its July production of "Two Gentlemen of Verona" on Boston Common to the mayor and First Lady Angela Menino.

The gestures are genuine expressions of thanks to Boston’s longest-serving mayor who retires at the end of this year, leaving behind a city far richer in arts and culture than it was when he took office. What’s more, he’s done it with next to no money.

If it weren’t for Menino, the Opera House, Paramount and Modern theaters on Washington Street would never have been rejuvenated, the Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts wouldn’t have been built, and the Strand Theatre would have continued to crumble in Dorchester’s Uphams Corner, say arts leaders involved in each project.

Absent a big assist and a slew of in-kind services from City Hall, Commonwealth Shakespeare Company couldn’t have produced free outdoor Shakespeare on Boston Common for the past 17 years, according to artistic director Steven Maler. Open Studios probably wouldn’t be flourishing in 12 Boston neighborhoods without the support of the mayor (who reportedly has visited each). Boston wouldn’t have its own poet laureate, public art walk, or a summer calendar packed with free city-sponsored events.

“The kind of help, the quality of help the mayor’s staff gives us — with permitting, public safety, advocacy, fundraising — is an indication of how passionate he is about bringing the arts to the public,” Maler says. That commitment is critical to cultural endeavors in Boston, he adds, “because there is no money.”

The city of Boston doesn’t own or invest in any of its major museums, theaters or concert halls. Nor does it make significant cash contributions to cultural institutions, programs and projects. The current operating budget for the entire Mayor’s Office of Arts, Tourism, and Special Events is approximately $1.1 million (roughly $1.86 per capita). According to Americans for the Arts, a Washington-based advocacy group, Boston consistently ranks among the bottom five of the 30 largest U.S. cities in what it spends annually on the arts. (San Francisco’s, for example, was $10 million and Seattle’s $7.5 million last year according to data collected by Americans for the Arts.)

Advertisement

The minuscule arts budget is a byproduct of state law that severely restricts Massachusetts cities and towns’ revenue sources. It also bars them from levying the kind of taxes, surcharges and fees (on meal and hotel tabs, for instance) that municipalities across the country use to support their art museums and concert halls, sports teams, parks and other public amenities. The city is “exceptionally dependent on a limited number of revenue sources, most notably the property tax,” according to The Boston Foundation. The Massachusetts capital funds more than half its operating budget with tax revenues from residential and commercial property, a severely constricted source in a city where 52 percent of land is owned or occupied by government and nonprofits, both tax exempt.

“To me one of the greatest of all his accomplishments is his capacity to leverage limited resources on behalf of a bigger agenda,” says Michael Maso, managing director of the Huntington Theatre Company. “Building a performing arts center is a civic activity. This city has no money to dedicate to those sorts of efforts, so it underwrites others’.”

The city of Boston and its Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) were indispensable in building the Calderwood Pavilion theater complex at the Boston Center for the Arts (BCA) in the South End, Maso says. Opened in 2004, it is now a bustling cultural hub that houses the Huntington’s 360-seat second stage, the Wimberly Theatre and the 200-seat Roberts Theatre, used by smaller companies such as SpeakEasy Stage.

Menino brokered a deal between the BCA and the Druker Company in which Druker agreed to build the “shell and core” of a performing arts facility as part of its bid to develop what is now Atelier/505, a high-end, mixed-use condo complex at the corner of Berkeley and Tremont streets. City officials, Maso says, marshaled the Huntington and BCA through the complex development process, from property clearing, to permitting, to arranging short-term financing, so the three-story, 35,000-square foot pavilion on a sliver of property between the BCA Cyclorama building and Atelier/505 could open its doors. The city kicked in just $3 million to the $20 million project, The Boston Globe reported at the time. However, Maso says, “the Calderwood never would have happened without the mayor and the BRA.”

In 1995, Menino launched what seemed like a quixotic quest to save a trio of unheated, unlit and rapidly deteriorating theaters on what was then a seedy stretch of Washington Street between Downtown Crossing and the dregs of the Combat Zone. A longtime preservationist, he convinced the National Trust for Historic Preservation to list the once-glorious Opera House, the former art deco Paramount movie house and the Modern Theatre among the country’s 11 most endangered landmarks.

It was a symbolic gesture. The city had no money to revive the playhouses; Menino was issuing a challenge to problem solvers with deep pockets. He managed to attract one in 1996 in David Anderson of Pace Theatrical, who later became president of theater management at Clear Channel Entertainment, which acquired and eventually foot the bill for a $54 million renovation.

It still took six years. Opera House neighbors objected to initial plans to save the building, rebuffed subsequent modifications and then sued the city in 2000 to block the redevelopment. The process dragged on for two more years, and developers were apparently getting skittish.

So in 2002, Menino did one of the things he’s known to do best: called, convened, pushed, prodded, rewarded and froze out the right people at the right time, keeping all interested parties at the table until a deal to bring the Opera House back to its original splendor was done that fall. The city put zoning and building permits and other approvals on a fast track and the theater reopened in with a touring production of “The Lion King” in July 2004 (in time for the Democratic National Convention that summer, as Menino had hoped).

“If it weren’t for Mayor Menino, the Opera House would have fallen down,” Anderson told the Globe the day the mayor cut the ribbon. Instead, it is Boston’s theater of choice for touring Broadway hits, and home to Boston Ballet.

Reviving the Paramount took longer. At City Hall’s behest, Millennium Partners, developers of the new Ritz Carlton Hotel and Condominium complex a block away, repaired and restored the Paramount façade and its 3,000-bulb marquee in 2002. But the house remained a shell inside until the city signed an agreement with Emerson College to develop what is now Paramount Center. The mixed-use historic theater complex — which includes a 600-seat art deco theater, 150-seat black box, screening room, classrooms and the offices of ArtsEmerson: The World On Stage — opened in early 2010. Suffolk University unveiled the Modern Theatre, a new performance space and dormitory, later that year — 15 years after Menino managed to get the buildings declared endangered.

“Who would have thought 20 years ago that the lower end of Washington Street in downtown Boston would be the showcase side of the street,” says ArtsEmerson executive director Rob Orchard, who adds: “The mayor’s largely responsible for that.”

As Orchard sees it, Menino’s contributions to the arts are part and parcel of his efforts to revive neighborhoods. “He’s been pretty rigorous about bringing back the landmark theaters or movie palaces in this neighborhood. And without him, they wouldn’t be here. The audiences wouldn’t be here. And all high priced condos [currently under construction across the street from the Paramount] wouldn’t be here either. These theaters have turned it into a destination.”

The Menino administration has struggled since 2005 to revive the long-dormant and dilapidated Strand Theatre in Uphams Corner, hoping to turn it into a local cultural attraction that will draw audiences to an underserved Dorchester neighborhood, observes longtime local activist and arts publicist Joyce Linehan. After trying and failing to find development partners, the city sunk $6.2 million in capital improvements into the building, and positioned the Strand as a youth arts and performance center, run out of the city’s cultural affairs office. The Strand has attracted more showcase performances and short-term residencies (by troupes such as Jose Mateo’s Ballet Theatre and Actors Shakespeare Project) each year, City Hall officials say, who are pleased to note that Fiddlehead Theatre Company announced in early May it is the Strand’s new resident theater.

To be sure, Menino’s relationship with the arts community has been strained at times. His ties to some of the city’s major cultural institutions, for one, have frayed recently over City Hall’s Payments in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program. In an effort to help offset the rising cost of city services and cuts in state financial aid, the city last year asked Boston’s largest nonprofits to make “voluntary” payments, equal to approximately 25 percent of what owners of taxable property would pay, on properties worth $15 million or more. The nonprofits’ “contributions” are expected to increase each year until 2016.

Ten cultural groups were tapped to participate in the 2012 PILOT program. According to a Boston Municipal Resource Bureau report, the Boston Symphony Orchestra and WGBH complied; the Museum of Fine Arts MFA complained and contributed about one fifth of what the city wanted. The rest appear to have ignored the request.

The PILOT disputes will surely continue once Mayor Menino leaves office at the end of this year. So too will the theaters, programs and artist services Menino, the self-described Ahhhhts Mayuh, has left in place.

A former arts and culture reporter for The Boston Globe and Boston Phoenix, Maureen Dezell is a freelance arts journalist and a senior editor at Boston College. Her website is maureendezell.com.

This program aired on May 29, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.