Advertisement

Should Massachusetts Raise The Minimum Wage? Here's What The Research Says

A key legislative panel held a public hearing Tuesday on a bill that would gradually hike the state's minimum wage from $8 to $11 by 2015, then peg future increases to inflation.

The proposal has provoked all the expected responses.

Unions and immigrant advocates have argued that a stagnant minimum wage hasn't kept up with inflation and must be hiked; business interests have warned that increasing labor costs in an already high-wage state will curb economic growth.

So who's right? Here's what the data says.

The Eroding Value of The Minimum Wage

First, a bit of background. Congress sets a federal minimum wage — currently at $7.25 — that every state must abide.

But 19 states, including Massachusetts, have set higher minimum wages. And nine states — Massachusetts is not yet one of them — index the minimum wage to inflation.

Here's a chart from the left-leaning Massachusetts Budget and Policy Center:

Massachusetts, as the chart demonstrates, has one of the highest minimum wages in the nation.

But without a hike, states like Ohio and Arizona that index to inflation will soon overtake Massachusetts.

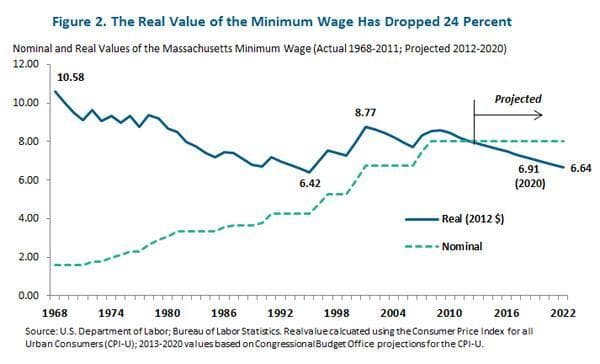

Proponents of a minimum wage increase note that the value of the minimum wage has eroded over time. In 1968, the state's minimum wage was $10.58 in 2012 dollars. Today, it's $8 — down 24 percent.

The real value of the minimum wage will continue to decline if lawmakers don't take action. From MassBudget:

But Michael Saltsman, research director with the Washington-based free market think tank Employment Policies Institute, said 1968 — the high-water mark for the real value of the minimum wage — is an arbitrary starting point.

Advertisement

In 1938, for instance, when the federal minimum wage first went into effect, its value in 2012 dollars was just over $4 — substantially lower than today's federal or Massachusetts minimum wage.

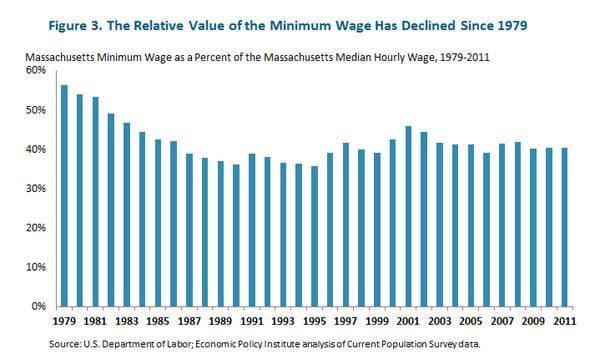

Noah Berger, president of MassBudget, replied that the nation is far wealthier than it was in the 1930s or even the 1960s. And the incomes of low-wage workers, he said, haven't kept up with the state's median wage.

Again, from MassBudget:

Saltsman countered that an increase in the minimum wage is not a particularly efficient anti-poverty strategy.

His analysis of 2012 census data for Massachusetts finds that the median family income for the roughly 153,000 people who would be impacted by an increase from $8 to $9 — the first stage in the gradual rise to $11 — is $53,668.

That figure, needless to say, is well above the poverty level.

And it points to this reality: Many of those working minimum wage jobs are living with people collecting salaries of their own — parents, spouses and other relatives.

MassBudget could not verify or refute Saltsman's math Tuesday, but conceded that some substantial portion of those who would benefit from the minimum wage hike are not in low-wage families.

It is a standard dynamic. A 2007 study by the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office found that a hike in the federal minimum wage to $7.25, which passed later that year, would increase U.S. incomes by $11 billion — with only $1.6 billion going to families in poverty.

Still, Berger said some significant segment of the Massachusetts families that would benefit from a minimum wage hike are at or near poverty.

And providing a boost to a two-income family making $50,000 is a good idea anyhow, he argued. That family, he said, is probably struggling to get by.

Impact on Employment

The most contentious debate revolves around whether increases in the minimum wage lead employers to cut jobs.

Economists are sharply divided on the question.

An influential study by David Card and Alan Krueger, published in 1994, looked at fast-food employment in New Jersey after a minimum wage hike and found no discernible reduction in employment.

And 15 years later, economists Hristos Doucouliagos and T.D. Stanley published a "meta-study" of 64 minimum wage studies conducted between 1972 and 2007 and found that increases either have no impact or are too difficult — or too small — to detect.

Over the last five years, though, the debate has grown more intense.

Economists David Neumark and William Wascher have argued that the highest-quality surveys do, in fact, point to a decrease in employment. And the impacts, they've found, are particularly hard on low-skill workers.

University of Massachusetts Amherst economics professor Arindrajit Dube, among others, disagree.

One influential Dube paper, written with economists T. William Lester and Michael Reich, compared counties in bordering states — one of which passed a minimum wage hike and one of which did not — and found no negative impact on employment.

Neumark is sharply critical of Dube and his ilk. And their findings are a bit counterintuitive — higher labor costs should, in theory, mean fewer jobs.

But in a recent paper, John Schmitt of the left-leaning Center for Economic and Policy Research suggested some possible explanations for a minimal impact on employment. Among them:

- Companies may pass along the increased costs to consumers.

- Employers may cut wages for other, better-paid workers after a minimum wage hike.

- Higher wages may mean less turnover — sparing employers the cost of training new employees

The evidence for these explanations is incomplete, though.

Indeed, the research on the impacts of minimum wage increases is a bit opaque on the whole. It'll be up to Massachusetts lawmakers to sort through it — if they pay it any mind at all.

This program aired on June 11, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.