Advertisement

Negative Ads Take Center Stage In Senate Race. But Do They Work?

With the Massachusetts U.S. Senate special election entering the home stretch, the air war has grown increasingly nasty.

The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee and the independent Senate Majority PAC have poured at least $1.3 million into hard-hitting television advertisements warning that "you can't trust" Republican Gabriel Gomez.

Gomez has hit back with an ad of his own, calling the attacks "ridiculous" and labeling his Democratic opponent Edward Markey "everything that's wrong with Congress."

The back-and-forth suggests that one of the great truisms of politics — negative advertising works -- is alive and well in Massachusetts.

But is the truism true?

Political scientists, until now, have been virtually unanimous in their response: no.

New research, though, suggests the ground could be shifting.

'People Don't Like Candidates Who Attack'

Academics have long found that negative advertising can damage its target.

But Richard R. Lau, a political scientist at Rutgers University who co-authored a comprehensive review of the academic literature in 2007, said it is equally clear that attacks inspire backlash — canceling out any benefit.

"People don't like candidates who attack," he said.

Political professionals, to the extent that they're aware of the academic research, have mostly dismissed it.

"When reality and research differ, it is the research that is wrong," wrote Mark Penn, an adviser to former President Bill Clinton in a 2008 Politico piece titled "Negative ads: They really do work."

But as George Washington University political scientist John Sides has pointed out, there is no evidence that even the most famous negative ad of all — President Lyndon Johnson's "Daisy" spot, warning of nuclear apocalypse if his Republican opponent Barry Goldwater were elected — had any effect on the final vote.

Advertisement

And for every high-profile story of a "successful" attack ad, there is another, less publicized tale of a negative spot that failed.

The producers of the "Swift Boat" attacks on presidential candidate John Kerry also put the ex-wife of a New Jersey Democratic gubernatorial candidate on camera; that attack ad backfired.

Why, then, has the myth persisted?

Sides argues that political consultants have every incentive to claim, despite the evidence, that a certain kind of advertising "works"; that kind of pronouncement implies the sort of expertise that commands big paychecks.

But there are other, more innocent explanations for broad acceptance of the idea.

"Negative advertising does tend to be more memorable," Sides said. "So the presumption is, well, it must have an impact."

That, he said, may explain why the media gives outsize attention to attack ads in its campaign reporting — attention that only encourages more negative spots.

A Shift?

Attack ads have become an increasingly prominent feature of the American political landscape.

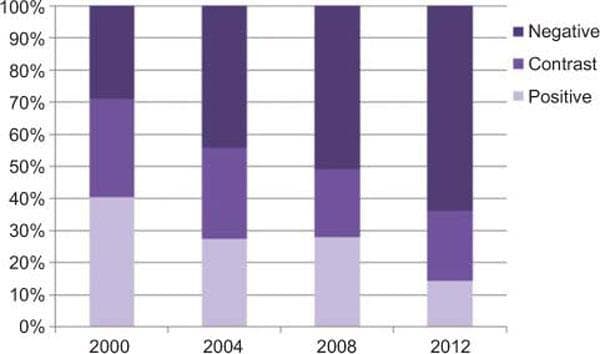

The Wesleyan Media Project put advertising from the last four presidential elections into three categories: negative, positive and contrast (in "contrast" ads, candidates promote themselves and attack their opponents).

The trend is clear.

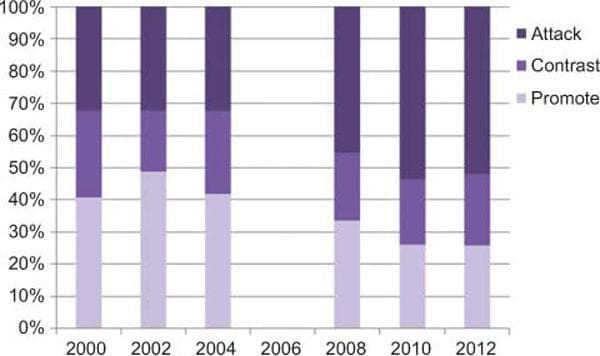

Something similar is happening in congressional races.

Researchers Erika Franklin Fowler and Travis N. Ridout, in a paper that appeared in political science journal The Forum, wrote that the candidates themselves have produced increasingly negative spots.

But the rise of the attack ad is powered, in no small part, by the growing role of outside groups in political campaigns.

In the 2012 presidential election, 85 percent of the ads produced by these independent organizations were negative — compared to 54 percent of those put out by the candidates and 51 percent of those aired by political parties.

And there is reason to believe that the outside groups have spawned not only more frequent attacks, but more effective ones.

The organizations aren't possessed of any special political genius. It's just that they don't have to contend with the sort of voter backlash that diminishes the impact of candidate-sponsored attacks.

At least one study backs up the theory.

Researchers Deborah Jordan Brooks and Michael Murov presented test subjects with positive and negative ads from a fictitious campaign.

Some participants were told the negative ad had no sponsor. Others were told a candidate sponsored the ad. And a third cohort was told an independent group was the sponsor.

The ad was more effective with the third cohort, they found, because there was no backlash effect.

It's just one study, of course.

And Sides, the George Washington political scientist, cautioned that it's too early to know if voters are really making distinctions between the sponsors of attack ads.

Gomez, in his reply to the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee and Senate Majority PAC ads, isn't making the task any easier here in Massachusetts.

After labeling those ads "ridiculous," the announcer says "Congressman Markey must think we're stupid," in what sounds like an explicit attempt to link Markey with the outside groups' attacks.

A Departure From The Last U.S. Senate Race

The high-profile role of independent expenditures in the campaign marks a sharp departure from the last Massachusetts U.S. Senate race, when Democrat Elizabeth Warren and Republican Scott Brown signed a "People's Pledge" designed to keep outside groups at bay.

A report by good government group Common Cause found real impacts: 36 percent of the ads in that race were negative, compared to an average of 84 percent in similar contests in Virginia, Wisconsin and Ohio.

The rise of negative advertising is a long-term concern: research suggests that it can erode voters' faith in government.

But there is little evidence that negative advertising depresses voter turnout; beware any post-election claims that low turnout in the Markey-Gomez race had something to do with the nasty tone of the race.

And with the effectiveness of negative advertising an open question, at best, political scientists suggest that the ad watch should focus elsewhere.

Research, for instance, suggests that when two sides spend about the same amount on campaign ads, they tend to cancel each other out. But a true imbalance can make a difference.

Volume, in other words, matters more than content.

Markey and the Democrats have wielded a significant financial advantage, to date.

And Washington publication The Hill reports that Senate Majority PAC is gearing up to spend at least $500,000 more on its ad attacking Gomez.

But The Washington Post reports that a pro-Gomez outside group calling itself Americans for Progressive Action will bring at least some balance to the air war in the coming days, with plans to spend about $700,000 in the race.

Federal Communications Commission filings suggest the group's ads could air Friday. Expect something negative.

This program aired on June 14, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.