Advertisement

Don’t Pigeonhole Him: An Interview With Kids Book Author Mo Willems

The man behind the loveable, hysterical Pigeon—you know, the one you’re not supposed to let drive the bus or stay up late, the bird who finds a hot dog and really wants a puppy—is Mo Willems.

Back in 2005, The New York Times was already calling the prolific Northampton author and illustrator “the biggest new talent to emerge [in the world of children’s picture books] thus far in the ‘00s.” He’s won Caldecott Honors three times—beginning with 2003’s “Don’t Let the Pigeon Drive the Bus!”—and Emmys six times for his previous work as a writer and animator for “Sesame Street.”

“I only write 49 percent of the book and the audience puts in the rest,” Willems likes to say.

He has just published three new books—“A Big Guy Took My Ball,” “That Is Not a Good Idea!” and “Don’t Pigeonhole Me!” (collecting two decades of his “sketchbook” zines)—and opened two exhibitions of his work. “Seriously Silly: A Decade of Art and Whimsy by Mo Willems” showcases his children’s book art at the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art (125 West Bay Road, Amherst, through Feb. 23). “Mo Willems: Don’t Pigeonhole Me!” features his sculpture and two decades of more adult doodles at R. Michelson Galleries (132 Main St., Northampton, through Aug. 30).

I spoke to him last week about the Pigeon and Elephant and Piggie; about writing for children just beginning to read; about “Sesame Street” and scripting Elmo; about growing up (born in Chicago to Dutch immigrants; grew up in New Orleans with some summers in Holland); about hating Mickey Mouse and loving triangles; and about emotion and empathy. (Note: The order of some of the questions has been rearranged.)

So tell me about the Pigeon. He’s just so much desire and so much frustration.

“He’s the Pigeon. The fact is his first name is ‘The.’ That should tell you enough about who he is and where he thinks his place in the world is.”

Can you talk about putting character and emotion, relationships at the center of your stories?

“I think emotion is a very, very important aspect of the work that I do or try to do. Ultimately what I’m doing is I work under the theory of write what you don’t know. I have questions: How do you tell a friend that something that they’re doing is not as great as they might think it is? How do you keep these relationships going? I find that these are questions that are difficult for me as well. So I’m really trying to avoid being didactic in any way. So if I don’t understand something that’s probably means that it’s an interesting topic. Not that I’ve always done that. I’ve written a book called ‘Time to Pee!’ and I’m fairly good at urinating. It’s one of the few books where I feel that I’ve got greater knowledge than my audience.”

ARE YOU READY TO PLAY OUTSIDE?

You were born in Chicago?

“I actually was. I was conceived on the boat over.”

Tell me more.

“Well, when a man and a woman really love each other … I don’t understand that much more. But I certainly feel that I belong somewhere in the Atlantic more than in Holland or the States.”

Your parents came from Holland. Reading your books, I wondered if part of what we’re seeing is a Dutch humor. Is there a Dutch humor?

“There’s definitely a Dutch humor. The Dutch language is essentially German for funny people. Absolutely. The Dutch love British humor. There are a lot of crossovers there. Dutch humor can be fairly sharp. Our Christmas tradition is you buy everybody a gift that insults them, then you write a poem about their flaws and make them open up the insulting gift. That’s what we do for Christmas. … I would certainly say that I grew up in an environment, particularly when I was in Holland, where you had to be quick and witty or else you would be destroyed.”

So you were born in Chicago. How long were you there?

“Very briefly. Got a cup of coffee and then we left. I grew up in New Orleans. And New Orleans is a very storytelling town. And it has a very peculiar, idiosyncratic humor. Basically what people would do is they would all get together in bars and tell stories of colossally stupid things that they had done. When they ran out of stories, they would all run out of the bar and go do something colossally stupid and then come back and be able to talk about it.”

“Ultimately what I feel very strongly about is I have not rejected any of the eccentricities that I’ve experienced in my life. So everything that I’ve done has added up to what I am. So certainly the Dutch, coming from New Orleans, and I also spent time doing stand-up in England, that was very useful.”

You moved to New York to study at New York University and then you went directly into animation?

“I was a film school student and I discovered in my first couple weeks at class that in order to make live-action films you had to have friends, weather, location and money, and I had none of those things. But I could draw lots of people and make funny voices. I saw a film, an animated version of ‘Ubu Roi.’ I saw an Oskar Fischinger film. I saw ‘Gerald McBoing-Boing.’ And that was it, I was done."

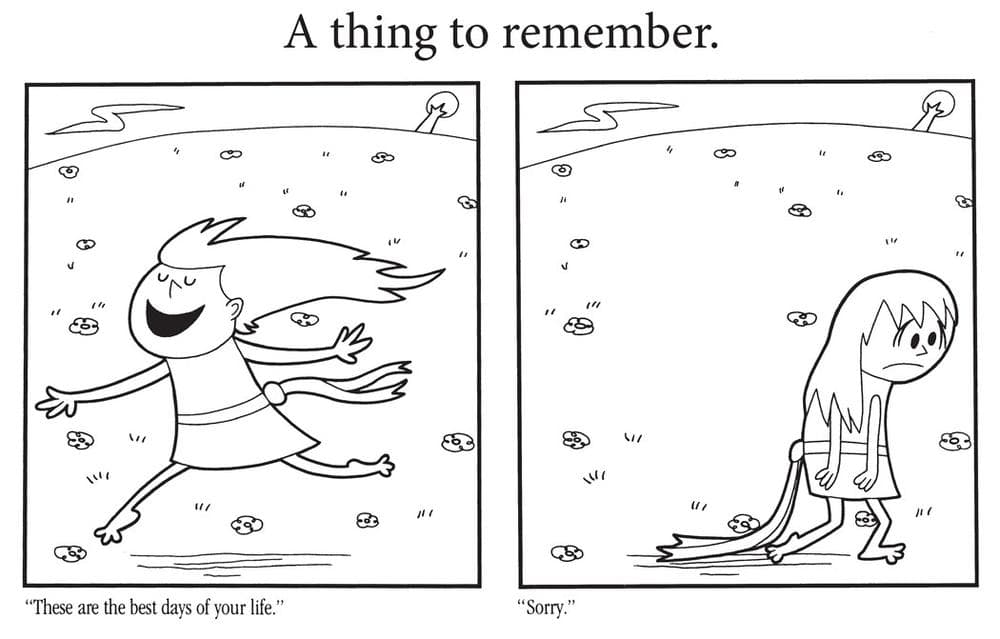

In your new book, “Don’t Pigeonhole Me!,” you mention the inspiration you got from mid-century gag cartoonists like Saul Steinberg and William Steig.

“It’s that the gags don’t have to be hilarious, they can be droll and that’s enough. I collect these volumes, these big fat volumes that look a lot like what we’ve made, and I started doing this when I was 19. I lived in New York City and there was a guy on Astor Place and he would save these books for me. And I would save up and get them and pour through them. These are the things I read a million times. And particularly Ronald Searle and Steinberg. But Searle in particular, it was great because everything was a triangle. I hated drawing circles. I hated Mickey Mouse. I hated the stretch and squash, circley cute stuff. And here was a guy who was making incredibly emotive things only with triangles. So I saw his stuff and I said, ‘Wow, I’m never going to have to draw a circle again. This is awesome.’”

Is drawing circles difficult for you?

“Funnily enough now my characters are circles. Elephant is. Piggie is. Pigeon is. But I think that by drawing triangles for 10, 15 years it allowed me the freedom to sort of draw circles on my own terms. And what that meant is flat. I like flat. I like that expression that you get from a two-dimensional drawing. A circle inherently starts to look three-dimensional and that point, the Disney animators called it the ‘imitation of life,’ it’s one of the reasons I hated them because who the hell wants to imitate life? Here’s a chance to make magic and you’re going out and imitating life. That just seemed like a waste. I want to create joy, but a unique non-living beauty.”

HOW TO GET TO SESAME STREET

Then you did writing for “Sesame Street”?

“By the time I was at ‘Sesame Street,’ I was working in two departments. I was making short animated films, essentially as an independent filmmaker. They would contract me and I would shoot it and do everything and whatnot. I wasn’t a studio animator. And then I was a scriptwriter, which involved me essentially writing at home. We had writers meetings once every couple of weeks. So on the side I was making other films or commercials or eventually ‘The Offbeats’ and ‘Sheep in the Big City.’ I was able to stay at ‘Sesame Street’ while I was doing those other projects.”

“Here’s the great thing about ‘Sesame Street.’ I was really a young guy when I was a writer there. I really was learning, it was like going to graduate school. The great thing is you could write a script that wasn’t perhaps the best script in the world and these Muppeteers would make it funny. There’s something to be said about the anonymity of television and there’s also something to be said about writing stuff for people who are really talented. So every time I would go on set and see them sort of alter my script I would be taking notes.”

Do you have any exciting Elmo gossip?

“No. He’s just a wonderful red monster.”

When did you leave all that to become the celebrated master of children’s literature?

“I don’t think that is exactly how I saw it. … My life is stumbling forward with lots of failures. I very much wanted to do picture books. I had for a long time. I spent a long time finding an agent. My agent spent many years trying to sell my books. And I had a child and I had a very selfish sort of decision, which was I was writing for children and I was never seeing my kid because I was working these terrible hours. So I figured if I’m going to work terrible hours I might as well do it at home. Really my first inspiration was maybe I can just be at home and watch my kid grow up. And there was a crossover—I was still in TV and making books for several years. The books didn’t suddenly, magically take off. They did very well, but I still had to work in television for a while.”

WE ARE IN A BOOK!

Can you talk about your interest in beginning readers?

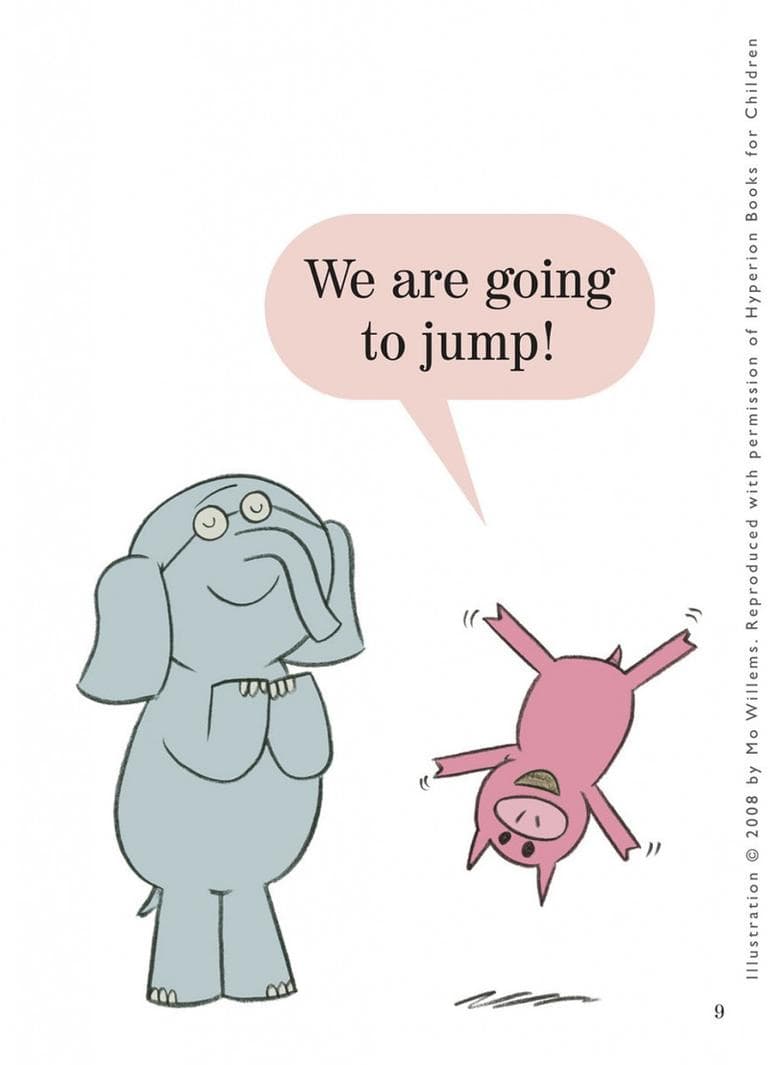

“Early readers are extraordinarily challenging. Before I was doing the [‘Elephant and Piggie’] early readers, I was writing picture books almost entirely. And the great thing about picture books is you’re writing for illiterates. So that means that you can use really big words because there’s somebody else, there’s the orchestra reading this for the audience. But once you get to an early reader you’re really limited. And that challenge was very fun. Each of these books usually has only 40 to 50 unique words. And I vet them all. And I check them. I try to make sure they’re monosyllabic. Every now and again two or three syllables get in. So it’s this great puzzle: How do you create emotion and frustration and anger and joy with these very, very simple words?"

You talk about the difficulty of doing early readers. Why do you care about doing early readers in the first place?

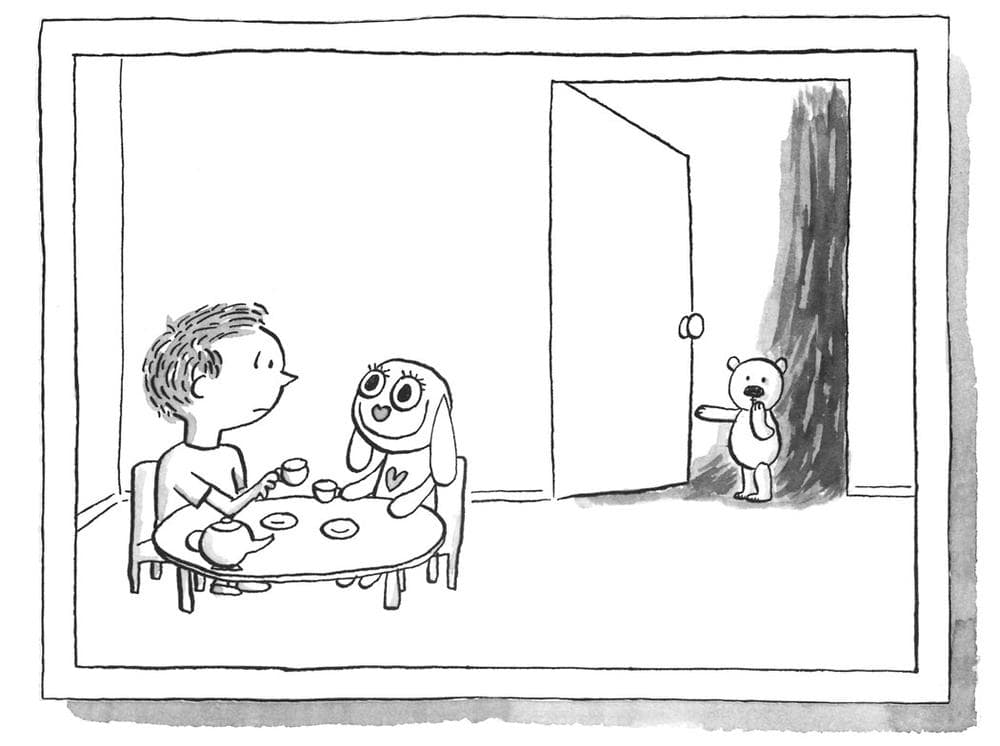

“Part of it really was I had been told by all sorts of authors and people I respected, ‘Picture books are hard, but early readers that’s as hard as it gets.’ There’s an element of because it’s there. I also think it’s a fantastic time in your life when you’re starting to decode. A lot of things happen. You start to lose a lot of your memory, that faculty of being able to remember everything disappears as you start to read because you don’t need to remember everything because you can get it somewhere else. You can access it if you want to. It also means a great degree of independence. One of the things that’s important to me is that my books are played not just read. So I wanted it to be in dialogue so that younger readers could read a real book even if they’re only reading one character. So that’s the transition. I saw that with my own daughter when she was learning to read. I would have to take some of the lines and she would get some of the lines and it would build up that way. But it wasn’t natural in the books. But here mom or dad can say, ‘I’ll be Elephant, you be Piggie.’ You’re working together, but you still have the accomplishment of finishing a real book. It’s 64 circles, it’s 56 pages, it’s massive.”

The “Elephant and Piggie Books” are partly about working out problems. They’re so well adjusted.

“I would say the complete opposite. For the Elephant, Gerald, the cup is half full of poison. And Piggie, she’s a joyful soul, but she could quite easily walk into a wall and not realize it. I think that they’re like any working set of friendships or relationships, they need each other because they supply for the other elements that they don’t have. What they are willing to do is to admit their mistakes and admit how much they care for each other. And that is perhaps rare, unfortunately. But, no, they’re very poorly adjusted.”

On the one hand your most recent Pigeon book, “The Duckling Gets a Cookie!?” (2012), is teaching manners to the Pigeon and to the reader, but it’s also about the revelation that the Duckling is playing the angles. What’s that about?

“You are now asking questions that are beyond me. And the answer to all these questions is going to be the same: We live in a sick, sick world.”

Your books seem to speak about the obligations we have to each other.

“That’s a very interesting look at it. I do feel that we have obligations to each other as a culture and as people. I’m not really trying to do anything. But for myself as a person, and maybe this comes out in the book, I am trying to engender empathy. I would like to be more empathetic. And I would like people to be more empathetic to me. So if that comes through that’s great. I think that empathy is the key to all of this. All of the problems that we have in the world are ultimately problems of no empathy, people just living in their own shoes and refusing to try on others.”

This article was originally published on June 25, 2013.

This program aired on June 25, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.