Advertisement

'Moral Injury': Gaining Traction, But Still Controversial

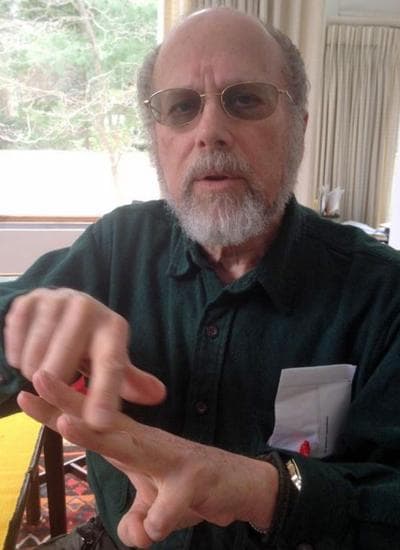

One after another, veterans would come in to Jonathan Shay's office with stories of a death they couldn’t shake. Some were events you’d expect during war, others were unthinkable, unforgivable and haunting. Most of these stories were not part of the veteran’s combat medical history. Shay, a psychiatrist at the Department of Veteran Affairs clinic in Boston, would add them.

There was the Marine corporal who ordered subordinates to help him gun down 17 disarmed Vietnamese after the his commander told him “we don’t need no prisoners.” The corporal, a Catholic, had to goad his men to participate. Years later, he had become a gutter drunk, Shay says, convinced he’d “led his men into mortal sin.”

And Shay remembers the story of a Marine scout sniper who couldn’t stop replaying a particular moment from the assault on Fallujah in Iraq. A well-hidden enemy sniper had hit several members of the Marine’s unit and “when the scout sniper finally located his enemy sniper in his scope,” Shay explained, “he realized that he was wearing what we would call a 'snuggly' baby carrier. There was a baby strapped to his front.”

The Marine killed the sniper and the baby.

“His view of his duty to his brother Marines and his job description was to take the shot,” Shay said. “It’s part of a terrible curse of snipers that they actually see their weapons doing their work. He took the shot and it did its work and he’s going to live with that for the rest of his life.”

Constructing A Pattern

The vets who came to see Shay were living with these memories but they were not at peace. After hearing similar stories again and again, Shay constructed a pattern: a soldier betrays his or her sense of what’s right, under orders, in a high stakes situation. By the mid 1990s, he started calling the condition that results "moral injury."

Imagine someone you trust, telling you to do something you feel is deeply wrong, in a possible life and death situation. And you do it.

“You will discover your body reacts," Shay said. "Your guts churn, your heart begins to pound, you may get sweaty. It’s a horrible thought experiment.”

The experience is not new. Shay says the concept of moral injury comes right out of the "Iliad" and thousands of years of war. But it’s not an established condition. Shay, a 2007 MacArthur "genius grant" recipient, has been writing and lecturing in an effort to change that.

“I describe myself as a missionary from the veterans that I’ve served,” Shay explained. “They don’t want other young kids wrecked the way they were wrecked, so listen up.”

Advertisement

Shay urges military leaders, members of Congress and audiences across the country to support three changes he says would help prevent moral injury:

- Send troops “into danger together and bring them home together”

- Provide better training and support for troop leaders

- Make training for all troops “prolonged, cumulative and highly realistic”

Shay says lobbying for these changes has been “a lonely pursuit.” But that's beginning to change as a growing number of researchers are focusing on moral injury.

“Shay started the ball rolling, using literature to raise the consciousness of care providers and families,” said Brett Litz, a clinical psychologist with the VA's health care program in Boston and a professor at Boston University. Now, Litz and colleagues are attempting to build out the science.

Studies of active duty soldiers and Marines are underway to determine for the first time how often moral injury occurs, what it looks like and how to treat it. At Camp Pendleton in California, Marines who suspect they have post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, come in for therapy and are asked this question:

What currently is the most distressing and haunting experience that you had in multiple deployments?

Researchers use the question to get at a soldier's "principle wound."

Litz says when you sort Marines’ responses to establish their main wound, only about one-third of Marines actually have PTSD or anxiety from a traumatic, often life threatening event. Another one-third focus on loss, often the death of a close friend. And the final one-third describe a moral injury.

Litz says of these three groups, Marines with a moral injury appear most at risk for hurting themselves.

"Self-harm might arise because you feel unforgivable and damned and you may feel at a very deep level that you deserve to suffer,” Litz said. “So how is someone going to behave if they feel that they deserve to suffer? They may abuse drugs, they may drive dangerously, some may not even care whether they live or die."

Marines with a moral injury or those mourning a loss may also feel hopeless, Litz said. Others actively sabotage their lives.

“If you feel undeserving and unforgivable, you may take one step forward in your relationships and your workplace and then three steps back," Litz said. "You may feel guilty if you feel good.”

Litz is in no rush to turn moral injury into a medical condition, but he and his colleagues are testing a treatment with Marines on the base.

“We want to promote — to a degree — a confession-like experience,” Litz said. “We do this in a highly evocative, highly emotionally charged way. We want it to be very real and very powerful.”

In this charged moment, a Marine begins a conversation with their most compassionate, forgiving loved one — someone who will listen to all the horrible details of their injury and still remind the Marine “that they can have goodness in their life,” Litz explained. “That they deserve it, but that they have some work to do. And it’s the work to do which we’re just setting in motion.”

It’s work that may continue for years in therapy, volunteer work or maybe in a church, synagogue or mosque.

Litz says he’s proud that the military is funding such controversial research.

“It’s controversial to think that war can be damaging about morality,” Litz explained. “After all, service personnel are ordered to do what they do, and they’re trained to do what they do. So how could it be damaging, morally and ethically? And we were funded by the military to do this larger trial, which I think is extraordinary, just extraordinary.”

'Inner Conflict'

But funding research about moral injury doesn’t mean the Marine Corps has embraced the concept.

“Marines don’t like to say, 'I’m being injured by doing the very thing I’m being trained to do,' " said Navy Chaplain Mark Smith, who helped negotiate the official doctrine on moral injury for the Marine Corps in 2008.

In short, the Marines have adopted the concept, but renamed it “inner conflict.” Marines would tell Smith, “I understand I can get injured while I’m doing the thing I’m trained to do, but when you say the thing I’m trained to do injures me, some of them at least struggle with that. So we avoided [the struggle] by sticking with inner conflict.”

Changing the name makes the concept more acceptable for Marines who need help, says Navy commander and clinical psychologist Andrew Martin. He used to direct the Marines’ suicide prevention program, and is now in charge of expanding community counseling and prevention programs at bases across the country.

“One of the goals of prevention is to get Marines talking to each other early about problems,” Martin said. “The Marines told us that the term 'inner conflict' resonated much more with them and they found that facilitates, more easily, conversations with one another.”

Using one term in Marine Corps programs and another in research surveys and test treatment can be confusing. It’s a sign that moral injury is an evolving, not yet settled condition. But Smith says the concept is gaining traction.

“I think it’s taking hold. I think people are paying attention and recognizing this is something we need to understand much better and we need research to back it up,” he said.

Martin says the military understands that any stressful situation — including moral injury — has the potential to increase somebody's risk for suicide. But he says rising suicide rates within the military go beyond any single factor.

"When dealing with suicide prevention, the important thing to keep in mind is that we have to consider all variables," Martin said. "So if this is one, it's important to address just like all others."

Some veterans argue they’re not the only ones who need help, forgiveness and healing. Former Marine Capt. Tyler Boudreau says responsibility for all the times he gave a sniper permission to fire goes right up the chain to his commander and beyond.

“To what extent do you have responsibility for me giving permission to a soldier to shoot a person in Iraq?” Bourdreau said.

With that question, Boudreau is asking all of us to share the burden of moral injuries and help find ways to heal. And we have to start, Boudreau says, by talking about it.

This program aired on June 25, 2013.