Advertisement

Caveman Syndrome: Today's Killer Diseases Stem From Evolutionary Mismatch

By Karen Weintraub

CommonHealth Contributor

Cavemen didn’t have flat feet or type 2 diabetes. They didn’t need orthodontia or get impacted wisdom teeth. The ones who couldn’t see their prey – or predators – from far away didn’t live long enough to pass their nearsightedness on to their children.

Indeed, the vast majority of what ails us today — from leading killers like heart disease and cancer, to smaller health woes such as back pain — is the result of a mismatch between the environments we evolved in and the ones we now inhabit, argues Harvard evolutionary biologist Dan Lieberman in his sweeping new book, “The Story of the Human Body: Evolution, Health, And Disease.”

Lieberman, perhaps best known for his energetic advocacy of barefoot running (which he sometimes does), convincingly makes the case for a wholesale rethinking of how we live our modern lives based on overcoming these evolutionary "mismatches."

“Most of us in this room are probably going to die of a mismatch disease,” Lieberman told a capacity crowd Thursday night at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

Our bodies evolved as hunter-gatherers to walk 5-10 miles a day, eat a varied diet loaded with fiber and pack on fat in times of plenty to get us through the leaner times, he said. But instead, we live in an environment where we can drive to the mall, park close to the door and take the escalator up to the food court for a dinner that barely needs chewing.

This mismatch has led, he suggests, to a proliferation of heart disease, cancer and diabetes – which were nearly unknown to our prehistoric ancestors, as well as disabling conditions like low back pain and autoimmune problems.

Advertisement

(Full disclosure, Lieberman is a long time acquaintance.)

Looking at health from an evolutionary point of view suggests new approaches to prevention and treatment.

Through this lens, it becomes clear that low back pain is the result of muscles weakened by spending most of every day relaxing in a comfy chair, Lieberman says.

Instead of the extra lumbar support that some would suggest to allow the back muscles to rest, this evolutionary approach would advocate a standing desk and more exercise.

We might have more luck fighting cancer, he suggests, if we view it as a disease of evolution, where certain cells win out by reproducing faster than others. Treating cancers with poisonous chemicals like chemotherapy might encourage the evolution of even more dangerous cells, just as some antibiotics and hand sanitizers can encourage the growth of more dangerous bacteria.

“Perhaps evolutionary logic may help us find a way to better combat this scary disease,” Lieberman writes in the book. “One idea is to promote benign cells to outcompete harmful cancerous ones; another is to trap cancer cells by first promoting those that are sensitive to a particular chemical and then attacking them when they are in a vulnerable state.”

Lieberman bases his arguments on his more than 20 years of studying and teaching evolutionary biology.

When he first started teaching about our evolutionary ancestry, he ended his lectures roughly 12,000 years ago with the emergence of modern humans and their spread across the globe. His students always wanted to know what happened next, how people continued to evolve; and he grew dissatisfied with the stock answer that we weren’t changing much.

Instead of evolving through natural selection – the process laid out by Darwin – human bodies have been mostly changing through cultural evolution, Lieberman now says. The biggest change early on was the movement to farming, which provided some survival advantage because there was more food available most of the time allowing women to have more babies – but which also led to new diseases and a harsher lifestyle.

It’s only within the last 200 years — thanks to sanitation and antibiotics — that humans have regained ground our ancestors lost when they traded hunting for farming.

Hunter-gatherers who survived childhood lived on average into their 60s, 70s and 80s, Lieberman said, while during the agricultural period, only a few were lucky enough to make it past their mid-50s.

Similarly, humans lost height when their diet narrowed from hunting to farming. Paleolithic men in Europe averaged about 5’8” research shows. Heights shrunk to 5’4” during the farming era, before rebounding recently to 5’10”, he said.

Lieberman does not advocate a return to the Paleolithic way of life. Food was crunchier and more fibrous, which helped our digestive systems and teeth, but infant mortality rates probably neared 50%. Humans, he notes, didn’t adapt over millions of years to be healthy in old age – but, rather, to reproduce more efficiently. So going back to this mythical past isn’t going to solve every health problem.

Instead, he says, we need to figure out how to keep the best of today’s lifestyle without reducing our quality of life through poor habits.

“We could be doing a lot better,” he says. “About 70 percent of all medical care in the United States is for preventable illness.”

Like many others, Lieberman, who has run 10 marathons and has seemingly boundless energy, focuses on diet and exercise.

“If there’s one evil ingredient out there it’s sugar,” he says, noting that Paleolithic diets relied heavily on fruit. But that was before fruit was bred for sweetness – back then, an apple was no sweeter than a carrot, he says. And people ate the equivalent of about 4-6 lbs of sugar a year — or about what we’d buy in one large bag from the grocery store. Americans now consume about 100 lbs of sugar per person per year.

Lieberman says the most urgent thing to do is require more physical exercise in schools — at least an hour a day.

For adults, he supports the kinds of higher taxes on junk foods and smaller sizes of drinks that recently got New York’s Mayor Michael Bloomberg into trouble.

The changes we’ve undergone in the past show that we’re capable of changing again, under the right circumstances.

“We’re not going to get out of [today’s medical] problems without understanding why they occur,” Lieberman says. “The way in which our bodies evolved is relevant to the way we live today.”

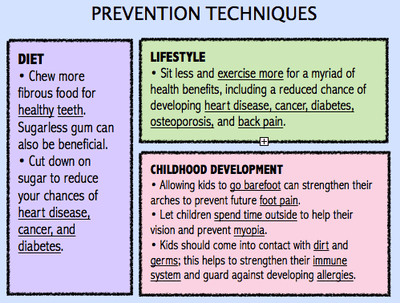

Here are some mismatch diseases and Lieberman’s suggestions (some backed by research, others more speculative) for preventing them:

Here are some mismatch diseases and Lieberman’s suggestions (some backed by research, others more speculative) for preventing them:Heart disease, cancer, diabetes: More exercise, less sugar

Osteoporosis: More exercise, particularly in late childhood and early adulthood

Myopia (poor distance vision): Spending more time outdoors as a child

Crooked teeth and impacted wisdom teeth: Chew more fibrous food and perhaps sugarless gum in childhood

Allergies and autoimmune diseases (such as Multiple Sclerosis and Lupus and even some autism): Allow kids to be more exposed to dirt and germs; prescribe probiotics along with antibiotics.

Foot pain and fallen arches: Avoid shoes with arch support; Let kids go barefoot more often

Back pain: Sit less, exercise more

Karen Weintraub is a health/science journalist based in Cambridge, Mass. Find her on Twitter @kweintraub.

This program aired on September 27, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.