Advertisement

Tired Of Painting The One Percent, John Singer Sargent Hit The Road

Maybe it was a midlife crisis. As the 20th century dawned, John Singer Sargent was frustrated by his stature as the most sought after portrait artist in the tony precincts of England and America.

“I have long been sick and tired of portrait painting, and when I was painting my own ‘mug,’ I firmly decided to devote myself to other branches of art as soon as possible,” Sargent complained in 1907 when he resolved to (almost) entirely abandon commissioned portraiture.

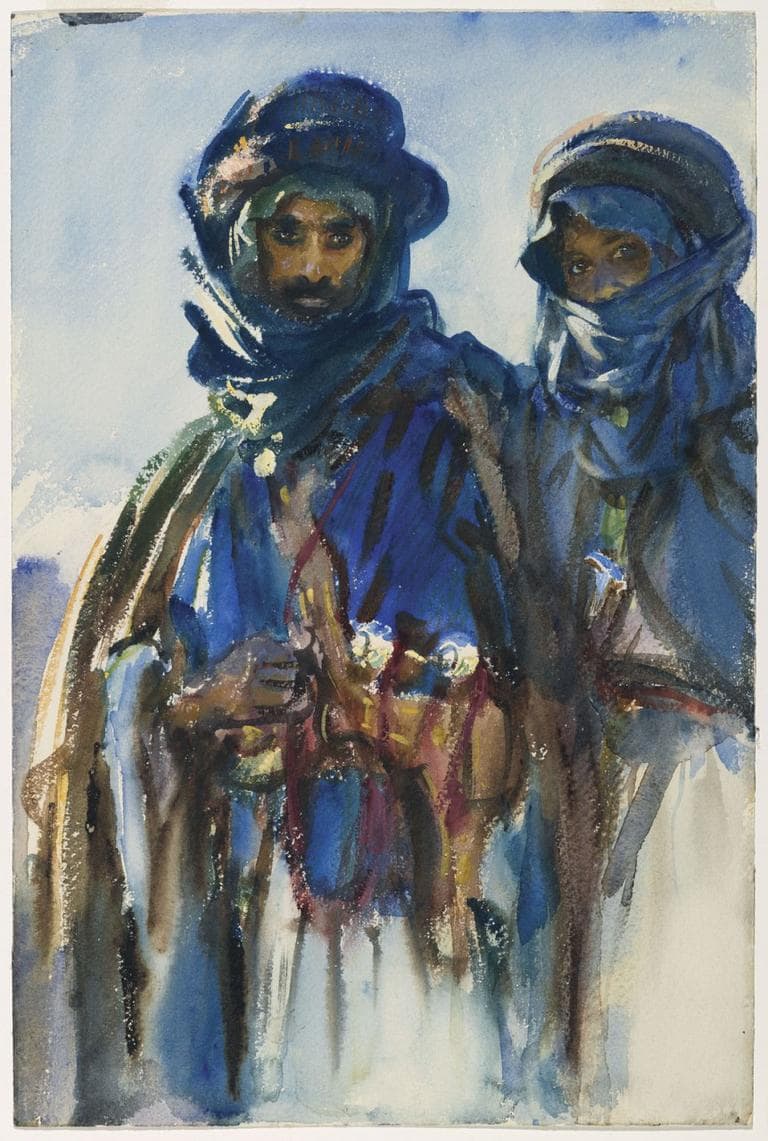

These commissions had brought him money and fame, but he wanted to follow his own muse. “John Singer Sargent Watercolors,” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts through Jan. 20, finds him in transition. He was still painting dashing formal likenesses of British aristocrats and wealthy Americans, but now in his mid 40s, he packed up his watercolors and took to the road to paint storybook adventures — Venice gondoliers, Italian quarrymen, Middle Eastern Bedouins, hermits in the woods, the gardens of Italian villas, Orientalist fantasies, and his friends and family on holiday in the Alps.

Traveling was Sargent’s natural state. He’s called an American, but he didn’t visit the U.S. until he was 21. He was born in Florence, Italy, in 1856 to an expatriate Philadelphia surgeon and his wife. Growing up, his family resided in France, Italy, Switzerland and Germany. He learned to speak four languages. He studied art in Florence, Dresden, Berlin and finally Paris, where he launched his portrait-painting career.

After initial success at the Paris Salons, he ruffled feathers in 1884 with his scandalously (for the times) sexy portrait of “Madame X” in a slinky gown with a strap falling down her shoulder. So he relocated to London two years later, where he built up his portrait business there and during trips to the U.S. in the late 1880s. It took off, and in the 1890s he added a series of commissions to paint murals in Boston — first at the Boston Public Library’s Copley Square branch, later at the MFA and Harvard.

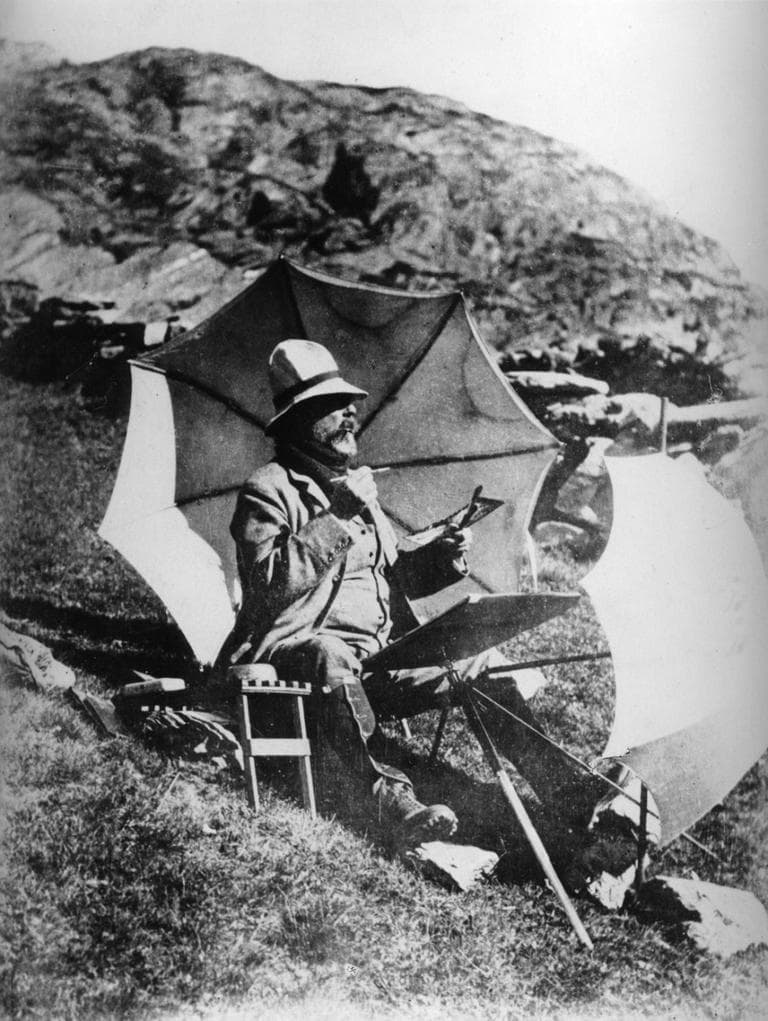

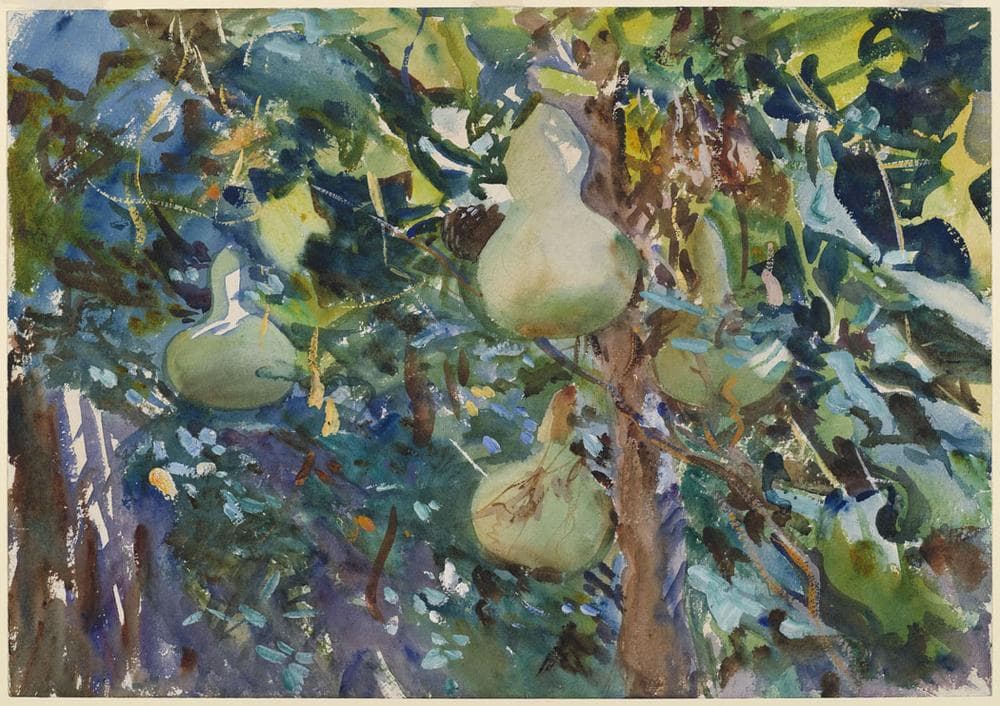

But he didn’t like being tied to his studio, so in the first decade of the 20th century, he played hooky by usually spending August to October traveling in Switzerland, Italy and Spain with a small circle of family and friends (including fellow painters). He continued to work in oils on these trips, but also painted dozens of watercolors — averaging about one each day. This was one more sign of how Sargent was trying to escape as he switched from polished portraits draped in shadows and his grandiose, gilded murals to loose watercolors alight with sun.

Advertisement

In this exhibition, for the first time, curators Erica Hirshler of the MFA and Teresa Carbone of the Brooklyn Museum, where the show debuted earlier this year, bring together 92 Sargent watercolors from the “two most signification collections” of these paintings, which the two institutions acquired by purchasing the entire contents of Sargent’s only American watercolor exhibitions in New York in 1909 and ’12. (Not included are Sargent’s watercolors reporting on World War I.)

“Sargent Watercolors” focuses on work from 1901 to ’21, but mainly the span between 1903 and ’11. This corresponds with the years Pablo Picasso and George Braque were inventing Cubism in France, but in England and the U.S., Sargent still ranked as an artistic leader.

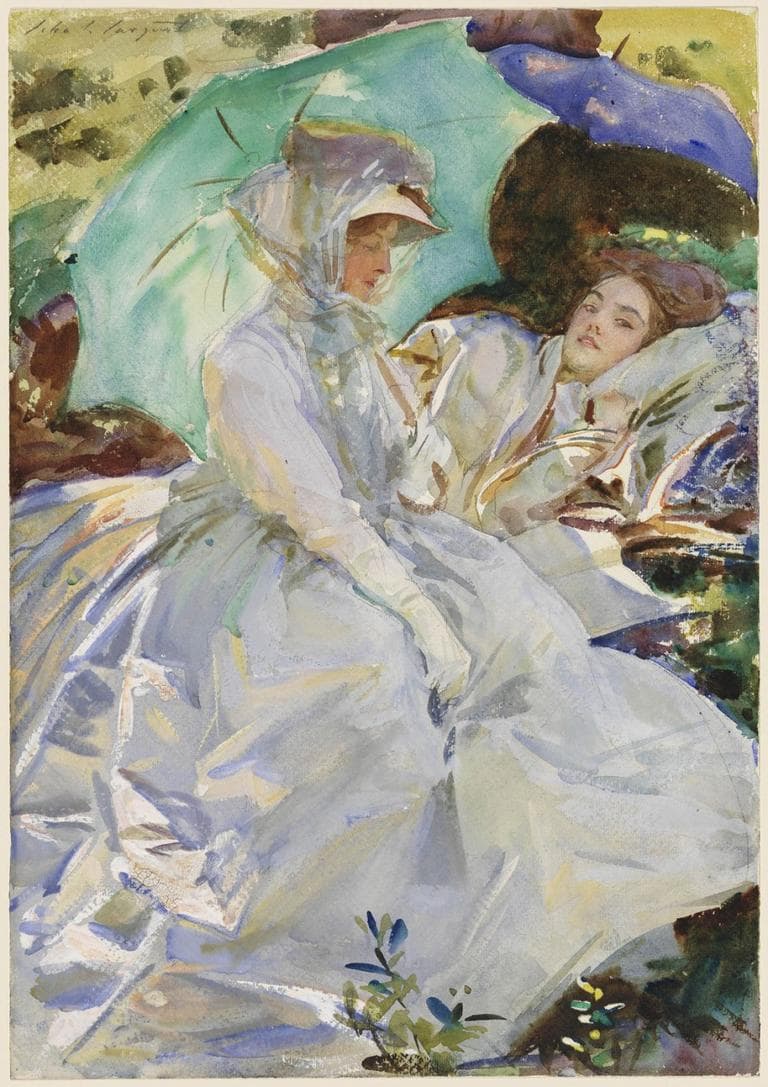

Sargent's signature talent was incredible marksmanship, which is part of why his paintings are so suave and dashing. He made it look quick and easy, as if every brushstroke was always put down in just the right spot, even though achieving this spontaneous appearance generally required numerous sittings with his subjects. Similarly, his watercolors feel as if he’s reporting just what he found, but he often posed the people or — as in his watercolor “Zuleika” — attired the young women in his company (usually his nieces) in Turkish costumes and cashmere shawls.

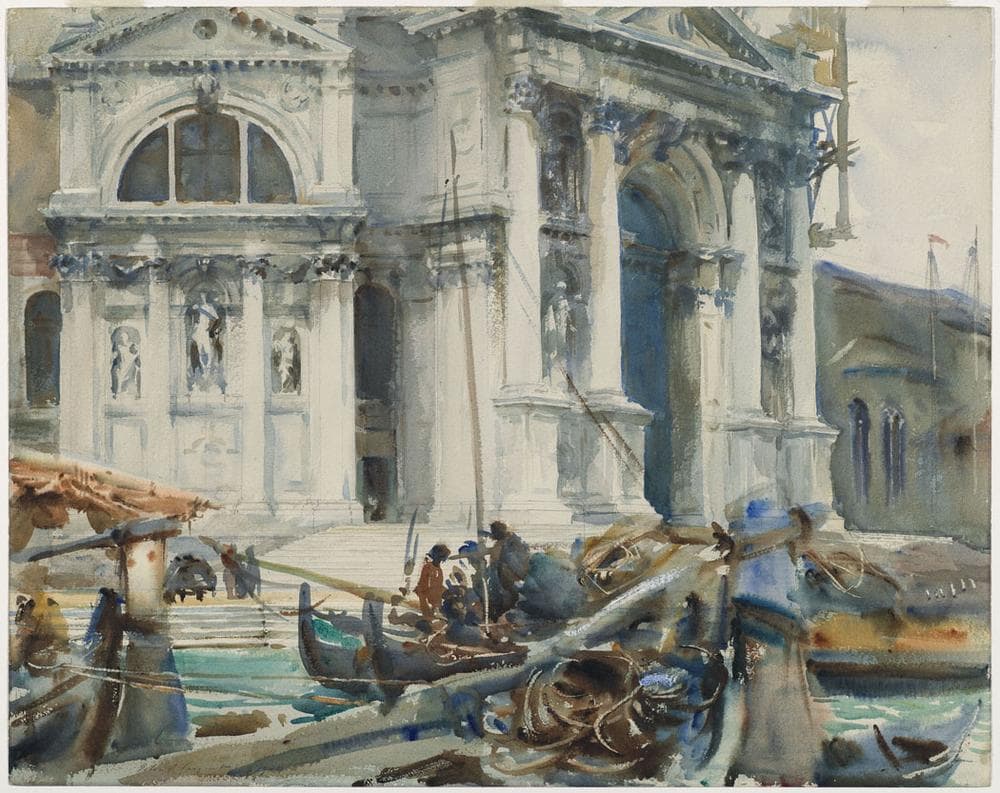

You can discern his process in his 1910 watercolor “Villia di Marlia, Luccca: A Fountain," depicting potted lemon trees and statues of lounging Roman river gods serving as fountains for an Italian garden pool dotted by white ducks. He penciled in the basic outlines and forms, then went into detail with transparent washes of watercolor applied on top with brushes and sponges (not necessarily in alignment with the pencil). Here, he uses the dark blues and browns of the background foliage to outline the sun falling across the bright green lemon tree leaves.

Unlike oils, which allow artists to paint over or paint out the pigments put down, watercolor doesn’t tolerate much reworking. So generally artists begin with lighter colors, then add more and more dark. At times, Sargent used wax to resist watercolor and protect lighter lower layers. Or he scratched down to reveal the white of the paper with a knife or the end of a brush. Sometimes he finished by adding daubs of lighter opaque watercolor atop dark sections. These techniques helped Sargent animate his scenes with the drama of light and shadows.

In the watercolors, Sargent returns to earlier interests. In his 20s, he’d painted French oyster gatherers, a Spanish flamenco dancer, Moroccan architecture, a Paris orchestra, and a woman dancing the tarantella on a rooftop on the Italian island of Capri. He had a sweet tooth for the rustic picturesque, for Orientalism, for the “exotic.”

A favorite book was English writer Charles Doughty’s 1888 memoir “Travels in Arabia Deserta.”

In the 1880s, inspired by his friend Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, Sargent had flirted with French Impressionism. “He wasn’t an Impressionist, in our sense of the word, he was too much under the influence of [the French portrait painter] Carolus-Duran,” Monet said.

Rather, Sargent at times adopted what you might call American Impressionism like his contemporaries Childe Hassam, Frank Benson and Edmund Tarbell. He imitated the surface look of the French avant-garde without really getting the soul of it, essentially creating a lite version of Victorian academic realism.

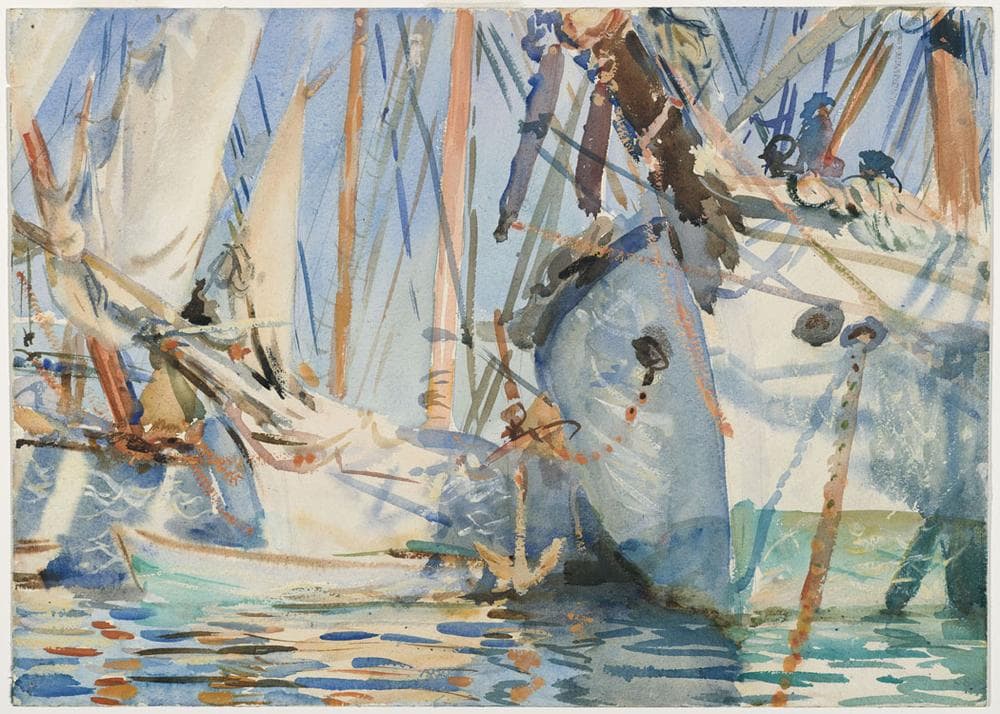

Sargent modulates his virtuoso marksmanship through the loose, expressive brushwork of Impressionism in the dashed waves of his watercolor “Venice: Under the Rialto Bridge” (1909) and the stout sailing ships and shimmering harbor of “White Ships” (about 1908). His watercolors are more showy in their brushwork than his oils, more effervescent in their effects.

For all Sargent’s skill, a liteness pervades his art. It’s a bit like the tension between the powerfully alluring glamour versus the shallow eye-candy of fashion photographers like Annie Leibovitz or Mario Testino. In his watercolors, you sense it in his hues, which lack the vividness of water-based paintings by his contemporary Winslow Homer or artists who came after like Georgia O’Keeffe and Edward Hopper.

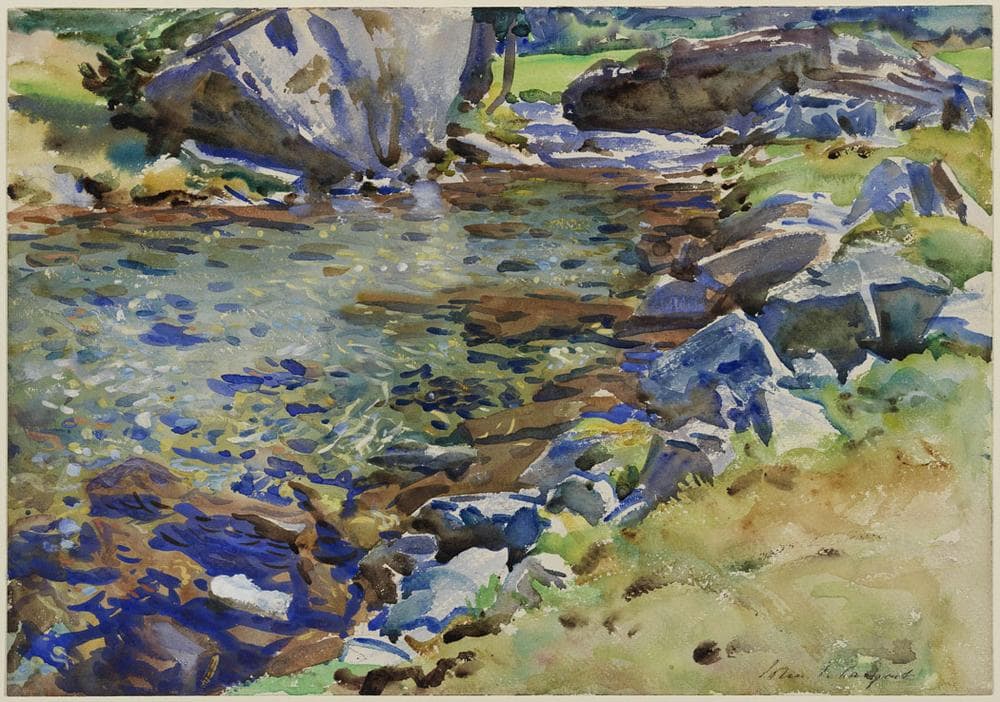

This is especially apparent when you compare two of his paintings of clear mountain streams—his watercolor “Brook Among Rocks” (1906-08) and his oil painting “Val d’Aosta (A Stream Over Rocks)” (about 1907-08). In the oil painting, the colors are more full bodied, and the whole scene is crisper, more in focus, though still emphasizing the play of thickly dragged brushstrokes. “Val d’Aosta” better captures the reflection and animation of the quick water, with plants waving in the flow. The watercolor has less feeling of transparency to the brook. It’s less about what Sargent was looking at and more about how he painted, more about his exquisitely skilled performance.

Perhaps that was what he was seeking in the modern styles—to escape from his formal portraits’ focus on others and to make art that showed more of himself.

“I have an entirely different feeling for sketches and studies than I have for portraits which are my ‘gagne-pain’ + which I am delighted to get rid of,” Sargent wrote in a letter to a friend in 1909. “Sketches from nature give me pleasure to do & pleasure to keep.”

This article was originally published on October 21, 2013.

This program aired on October 21, 2013. The audio for this program is not available.