Advertisement

Busing Left Deep Scars On Boston, Its Students

Resume

Second of two parts. Here's Part 1. Note: This report contains some offensive language.

BOSTON — Forty years ago this week, federal Judge W. Arthur Garrity's decision to undo decades of discrimination in Boston's public schools was put into action. It was called court-ordered desegregation, but critics called it "forced busing."

For those who were here and old enough to remember, Sept. 12 1974, is one of those defining dates in history, like the day JFK was shot. It was the day desegregation went into effect.

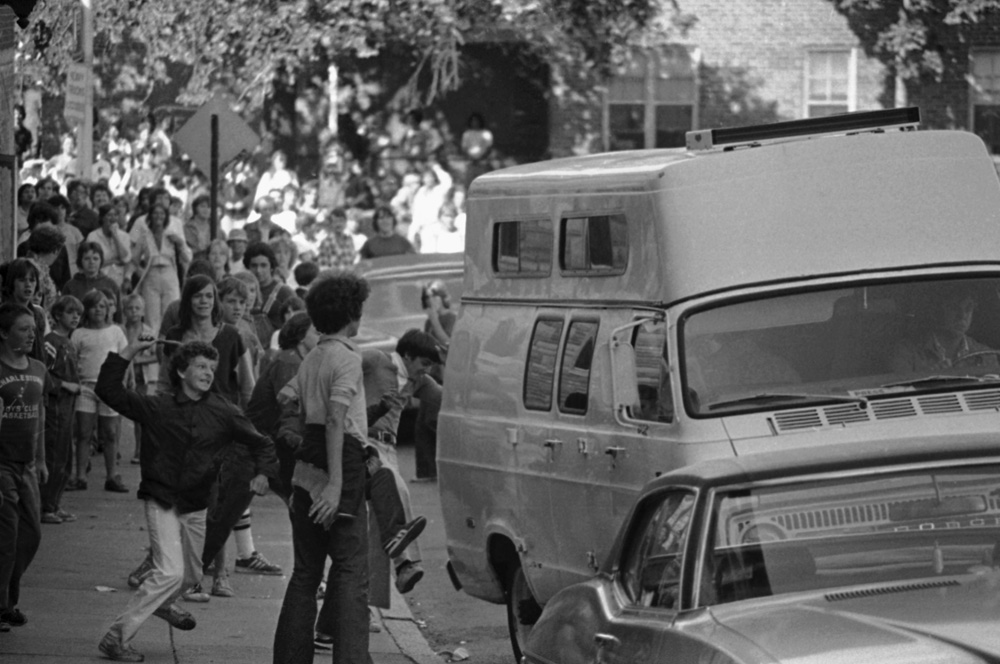

Hundreds of enraged white residents — parents and their kids — hurled bricks and stones as buses arrived at South Boston High School, carrying black students from Roxbury. Police in riot gear tried to control the demonstrators. Eight black students on buses were injured.

And the racism was raw. "They let the niggers in," one man said to a reporter then. Another said the same: "Then the buses came, and they let the niggers in."

Riding on one of the buses that first day was Jean McGuire, a volunteer bus monitor.

"Those kids were unprotected and what they saw was an ugly part of South Boston," she said in a recent interview. "They didn't see the really great people of South Boston."

"You’ll still see many victims of the busing decision that didn’t allow them to go to the school or get the education that they needed and deserved."

Former Mayor Ray Flynn

McGuire would become the first black female candidate elected to the Boston School Committee in the 20th century.

And Garrity's decision to use school buses to carry out his desegregation order became a potent symbol for opponents and supporters of the judge's ruling — supporters like McGuire

"It isn't the bus you're talking about," she said. "You have to be really honest, it hasn't a thing to do with transportation. Everybody in the suburbs rides a bus to school if they're not driving their cars. It isn't the bus, it's us, it's who you live next to. It's who you think your kids are going to marry."

McGuire says we're better off after Garrity's decision. "Absolutely, you had to break the mold," she said. But McGuire acknowledges there were mistakes in the judge's order.

"We would have never, ever paired South Boston with Roxbury as a start," she said. "It didn't make sense. There was too much enmity there. You'd start somewhere [where] there's a history of either the churches or businesses, sport teams, you know, things which people aren't suspicious [of], because there's a friendship there. You got something to base it on."

South Boston High School is four miles, and a world apart, from where Roxbury High once stood. Nearly all the students at Roxbury High were black. South Boston High was entirely white. And even sports couldn't bridge that gap.

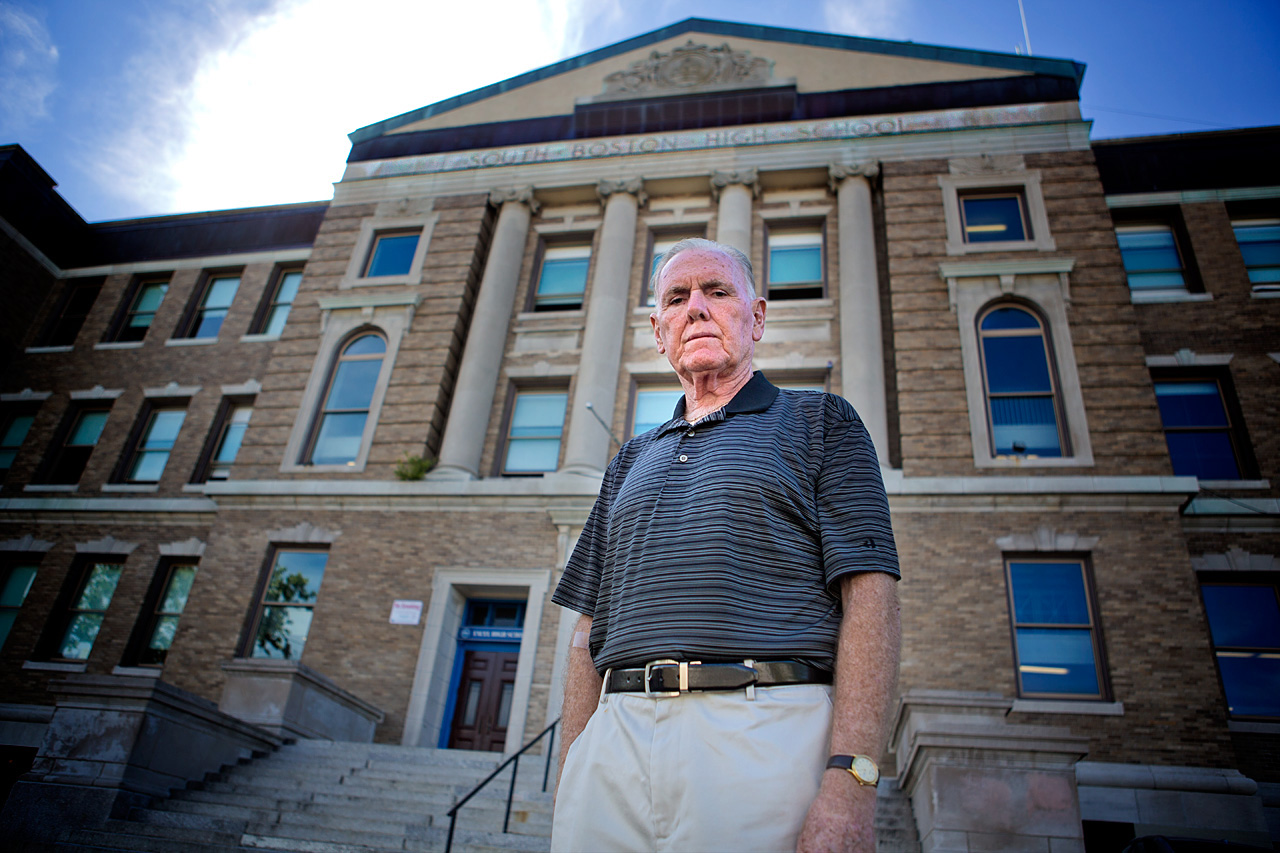

"It was a textbook case of how not to implement public policy without community input," Ray Flynn said recently on the steps of South Boston High. Flynn, who would later become mayor of Boston, was a state representative from Southie when busing began.

"I remember it very well," he said. "I was here every day during that whole ordeal."

When Flynn spoke, you could hear the sounds of hammers and saws as contractors were turning modest triple-deckers into upscale condos. Today longtime residents complain of gentrification and a lack of affordable housing and parking.

Now 75 and semi-retired, Flynn has lived his whole life in Southie, still an insular, tight-knit Irish Catholic enclave.

"To know South Boston, you really have to know the history of sports and that great tradition and pride that we have in this community, and neighborhood and sense of belonging," he said. "[We have] a special tradition and a special pride and sports was a major part of it."

And Flynn was a major part of sports there. High school class of '58, he was captain of three varsity teams. As a young probation officer in Dorchester he founded the city's first interracial sports league. He was a ballboy for the Harlem Globetrotters and drafted by the Celtics.

But teamplay didn't trump deep racial prejudices in Southie, which Flynn now downplays.

"There are racists and haters everywhere you go," he said. "You'll find them in any community and we had our handful of them over here in South Boston. They were the people that were most reported by the press, interviewed by the press. They were the most vocal."

But Flynn says their voices weren't heard by Judge Garrity or the appointed masters who carried out his court order. The divisions over desegregation were more than skin deep.

"They didn't understand the people or the neighborhoods of Boston," Flynn said.

The fundamental issues, Flynn says, were economic and class. Schools in poor, working-class Roxbury and Southie were deplorable. In Southie they lacked textbooks. In Roxbury some didn't have toilet seats. Students back then discussed who had it worse.

"If the court-appointed masters had only listened to the people in the black area, the white area, the Hispanic area, they would have gotten a different picture [of] what the parents wanted," Flynn said. "They wanted these windows fixed, they wanted these gyms repaired, they wanted a different curriculum. That's the kind of changes that they were looking for.

"You know, they have their most important possessions on the line," he added. "What is that? That's their children — their children's education and their future. Imagine some outsiders making decisions about somebody's children and their education and their future. You can walk around Roxbury, you can walk around South Boston, you'll still see many victims of the busing decision that didn't allow them to go to the school or get the education that they needed and deserved."

Forty years ago, Regina Williams of Roxbury rode the bus to South Boston High that first day of desegregation. In a recent interview, she said it was "like a war zone." Then she said:

I said, 'Ma, I am not going back to that school unless I have a gun.' At 14 years old. 'I am not going back to that school.' I just quit. I quit school. I had all this time on my hands. And what happened from there, you end up doing drugs, you end up getting pregnant out of wedlock, because there was nothing to do. You didn't have to go to school, they didn't have attendance, they didn't monitor you if you went to school. It was your choice. Either you go to school and get your education and fight for it, or you stay home and be safe and just make wrong decisions or right decisions. All these things that affected me goes back to busing. Lack of education. Lack of basic training and reading. Lack of basic writing. It's embarrassing, it's pathetic. You feel cheated. You don't want to tell anyone you never learned how to write because no one taught you.

Williams eventually got her GED, graduated from college, dropped out of grad school to care for her disabled grandchild, and now is studying for her real estate broker's license. She lives in Roxbury.

To the north, across Boston Harbor in a different neighborhood, there's a different perspective on court-ordered desegregation.

"It totally tipped the way of life in the city, and not to the good," said Moe Gillen, a lifelong Charlestown resident.

Charlestown was part of Phase 2 of Judge Garrity's desegregation plan. In 1975, in an attempt to avoid the violence of South Boston a year earlier, Garrity named Gillen to a community council. Gillen was the only one out of 40 council members to oppose busing.

"I never felt it was a racial issue," he said in a recent interview. "I always felt and still feel that it's an economic issue. To interview someone like myself that's from the town, lifelong, and they wonder why my kids don't go to public school, and yet the yuppies that come in with families, their kids don't go to public school and there's no question about it."

Down the street from Gillen's home is the Grasshopper Cafe. He's a regular of customer and he jokes around with waitress Zaida Sanchez. She wasn't here 40 years ago to see the buses roll. She came here from Peru.

"I love Charlestown," Sanchez said. "I like the people from Charlestown, but I don't feel like a townie yet. But my kids are townie. They were born in Charlestown."

Once almost totally white, Charlestown is now nearly 20 percent Hispanic and 20 percent black. Still more than half the population is white, but white children make up less than 8 percent of the public school students.

Busing tables at the Grasshopper Cafe was Meaghan Douherty. She's a townie but goes to high school in Cambridge.

"I've attended Catholic school my whole life so my parents wanted me to continue it," Douherty said. "They wanted the best education for me so they sent me to private school."

When asked about public school, she said: "I think it would make more sense for me to go in my town. Then I wouldn't have to drive to school, waste gas every day. But I want it to be a safer environment so I think they need to work on making it a safer place to be in."

The use of buses to desegregate Boston Public Schools lasted a quarter of a century. Yet, the effects are still with us.

In the first five years of desegregation, the parents of 30,000 children, mostly middle class, took their kids out of the city school system and left Boston.

Today, half the population of Boston is white, but only 14 percent of students are white.

McGuire, the former bus monitor, is still a supporter of the 1974 desegregation order, and Ray Flynn is still an opponent. They don't agree on much, except the unexpected consequences 40 years later.

"We're going back to resegregation," McGuire said. "We have more all-black and all-Latino schools now than we had before desegregation."

"Boston has become a city of the wealthy and the poor," Flynn said. "And the school system has not improved as a result of busing in Boston all these years."

And a question can be asked: Where will we be 40 years from now?

Correction: An earlier version of this story inaccurately reported that Jean McGuire was the first African-American on the school committee. She was the first black female. We regret the error.

Later this month, WBUR is organizing an on-air busing roundtable. We want to hear from former BPS students who were bused to school in 1974. If that's you, and you're interested in participating in our conversation, please send a note to reporter Asma Khalid.

This segment aired on September 5, 2014.