Advertisement

If You Build A Crew Program For Overweight Kids, They Will Row — And Get Fitter

There was no comfortable place for 17-year-old Alexus Burkett in her school’s typical sports program of soccer and lacrosse and basketball.

"They don't let heavyset girls in," she says.

Alexus was "bullied so bad about her weight," says her mother, Angelica Dyer, "and there was no gym that would take her when she was 14, 15 years old. There was no outlet."

But Alexus has found a sports home that is helping her bloom as an athlete: an innovative program called "OWL On The Water" that offers rowing on the Charles River specifically for kids with weight issues.

She has lost more than 50 pounds over half a year, but more importantly, says her mother, "They've given me my daughter's smile back."

"It's given me a lot of good strength and it's making me more outgoing," Alexus says. "We're all best friends and we're all suffering with the same problem — weight loss — so we're more inspiring each other than we are competing against each other."

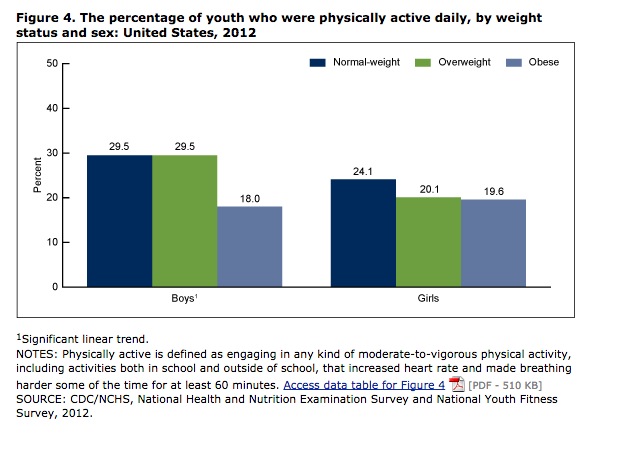

OWL On The Water offers a small solution to a major national problem: According to the latest numbers, 23 million American kids are overweight or obese, and only about one quarter of 12-to-15-year-olds get the recommended one hour a day of moderate to vigorous physical activity. Heavier kids are even less likely to be active, and only about one-fifth of obese teens get the exercise they need, the CDC finds.

"I know I need to be active, but please don't make me play school sports!" That's what exercise physiologist Sarah Picard often hears from her young clients at the OWL — Optimal Weight for Life — program at Boston Children's Hospital that sponsors OWL On The Water.

Advertisement

Many gym classes still involve picking teams, "and my patients are the ones that are always picked last," she says. "You're the biggest one, you're the last one, you're picked last, and you're uncomfortable."

They are strong, powerful people.

Sarah Picard

School fitness testing is important, Picard says, but it, too, can be an ordeal: "I have kids who sit in my office and tell me that they didn't go to school for a week because they wanted to miss the fitness testing," she says.

While many a coach might see bigger bodies as poorly suited to typical team sports, Picard sees them as having different strengths. Particularly muscular strength.

"What I've observed is that these kids are much better at strength and power-based activities," she says. And rowing is particularly good for them, she says, because though it is strenuous, it is not weight-bearing, and thus more comfortable for heavier bodies — yet a heavier, strong body can pull an oar much harder than a smaller person's body. The program begins by building on that muscular strength, she says, and then works on aerobic fitness.

When they join OWL On The Water, suddenly, "It's all kids just like them — all the kids who have felt left out," Picard says. Often, they are kids who sprint and stop repeatedly rather than endure long running distances — but they can row like demons. "They are strong," she says. "They are strong, powerful people, so when you put them in a program that caters to their strength set or ability set, they thrive."

The kids were clearly thriving at a recent practice session at the Community Rowing boathouse in Brighton. Community Rowing, Inc. (Motto: "Rowing for all") runs the training in partnership with the OWL clinic, whose exercise work is funded by the New Balance Foundation.

A dozen teens were rowing their hearts out on machines in the sun-filled training room, egged on by their tough-but-kindly drill-sergeant coach, Sandra Cardillo.

In one drill, they divided into pairs and one partner pushed for 30 seconds of maximal effort while the other played cheerleader. The sounds of rattling rowing-machine chains and comradely encouragement — "You got this!" "You can do it!" — filled the room. Then the partners switched off. They weren't competing against each other; they were competing against their own best scores, and supporting each other.

"You know that every single person in there is going through the exact same thing you're going through," says 13-year-old Emily Collins of Boston during a recovery period. "So it makes you just feel comfortable when you're coming in here, rather than going into something where people are so slim and they can do it 10 times better than you. It gives you the confidence you really need to help you in this world."

"The model of youth sports that has become more prevalent over the last couple of decades has become more of a model of <em>exclusion</em> versus inclusion."

Dr. Michael Bergeron

OWL On The Water is now beginning its 10th season, and "We're really moving the fitness needle," says Picard. Every season has brought a consistent improvement of 10 to 12 percent on the PACER test, a common measure of aerobic fitness, she says, and among the 24 kids in the program, "We had 88 percent attendance, because these kids talk about how they finally found their 'thing.'"

As far as its organizers know, OWL On The Water is unique nationwide — the only rowing program attached to a pediatric obesity clinic. But it has received requests from other children's hospitals and from rowing organizations about how it might be replicated, Picard says.

More broadly, communities around the country are launching many a creative effort to try to help kids — including heavier kids — get more exercise. They're trying to address not just the obesity problem but what some see as a perversion of American youth sports: What used to be all about casual pick-up games and leagues open to all has become ever more organized and selective and driven.

One particular paradox: Many teams hold tryouts — often right around now — and choose the kids who are strongest at a given sport. That may be the best way to win, but it can also mean that the students who are most in need of more fitness training — perhaps slower, perhaps heavier — are excluded from the very sports program that would give it to them.

"Sports can be part of the solution for promoting physical activity in youth, and set the stage for the rest of their lives," says Dr. Michael Bergeron, executive director of the National Youth Sports Health and Safety Institute. But "the model of youth sports that has become more prevalent over the last couple of decades has become more of a model of exclusion versus inclusion — looking for the kids that will 'make it,' the perceived 'best.' So a lot of kids get left off. They don't make the team."

If he were to reimagine school sports programs, Bergeron says, he would aim to broaden their enrollment: Some programs are even beginning to have no-cut teams, he says.

"You're not necessarily the ones traveling and going to different schools, but you're on the team and you're going to practice and if you want to be there, you're there," he says. "Obviously, that takes more funds, it takes more space, it may take more creativity in scheduling. But I think the idea of a no-cut system has a lot of advantages. A lot of ways to tangibly keep kids engaged in sports that maybe aren't the ones playing on Friday nights in the football game — but they're still involved."

And, he says, he would ensure that school sports involved more actual physical activity and less standing around.

Exercise physiologist Picard's dream would be to shift school gym classes to even more of an emphasis on the importance of fitness for health — and to put in fitness rooms alongside, or perhaps instead of, the old gymnasiums with their sticks and balls and games that emphasize competition.

A few schools are doing it, she says, and "I'd love to see the trend build more that way, where you emphasize wellness in the school — what does it mean to be fit? Physically, emotionally and in terms of knowledge? — and leave the competition for outside the school or after school."

Readers, agree? Disagree? What's your dream school athletic program?