Advertisement

A New History Of Fiber Artists Who Tried To Turn Craft Into Art

Around 1961, Lenore Tawney ordered a bunch of black and white linen thread to develop a new form of tapestry. For years, she had woven abstract textiles that hewed to traditional rectangular forms and hung on walls (or at least close to them).

“I only knew I wanted to make forms that would go up,” she later said. At age 54, living in Manhattan, she began to make weavings reaching as much as 13 ½ feet tall. They mixed tight and open weaves and often had an overall diamond shape a bit like stretched kites. Or perhaps like hammocks hung vertically. But the intensity of her geometries and the way she hung them floating in open space made them register like totems.

In the engaging exhibition “Fiber: Sculpture 1960-present,” which opens today at Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art and continues through Jan. 4, curator Janelle Porter identifies Tawney as one of the artists who pioneered tapestry’s transition, “taking the conversation away from craft to sculpture.” It’s still a contested legacy—and one often ignored.

“By and large this work sadly doesn’t get shown in museums a lot,” Porter says.

Rounding up 33 artists—the majority women, mainly white Americans or Europeans, mostly operating outside New York—Porter, in a major scholarly effort, “seeks to revise entrenched histories” by redefining the fiber art that emerged five decades ago as a “revolutionary” new category of art—both “painting and sculpture, drawing and sculpture, installation and painting, and most problematically, art and craft”—which, she argues, “positions fiber more firmly proximate to the explorations that have propelled art since the 1960s.”

Lenore Tawney’s approach was influenced by her studies at Chicago’s Institute of Design in the mid 1940s. The school was founded as the New Bauhaus by faculty who had been affiliated with the original Bauhaus school in Germany before it was shuttered in 1933 under pressure from the Nazis.

The German school had been founded by architect Walter Gropius, as he wrote in a 1919 manifesto, to create a “new guild of craftsmen” who would end the “arrogant class division between artisans and artists.” When the school closed, faculty scattered across the West, bringing their revolutionary hierarchy-busting ideas with them to Chicago, Harvard (where Gropius landed), Yale and Black Mountain College in North Carolina.

In the mid 1950s, Sheila Hicks, who would also go on to be a major figure in fiber art in the 1960s, studied at Yale with abstract painter Josef Albers, who had taught at the Bauhaus in Germany and then at Black Mountain. She also independently studied weaving with Anni Albers, Josef’s wife, who’d studied herself at the Bauhaus and argued for “threads to be articulate again and to find a form for themselves no other than their own orchestration, not to be walked on, only to be looked at.”

Such avant-garde approaches to fiber paralleled a turn toward eccentric abstraction by artists working in other crafty materials—like California sculptor Peter Voulkos, who taught ceramics at Black Mountain during the summer of 1953 and subsequently transformed his pottery into teetering, patchwork Abstract Expressionist slabs.

Advertisement

“Fiber” shows that as tapestry artists moved off the walls, we get things like Sheila Hicks’s 1966 “Banisteriopsis,” a pile of bound gold linen that forms its own low, soft wall. By then living in Paris, she was also one of the artists who made sculptures from cascading cords of brilliantly colored threads. “For me, it’s what has the emotion, the impression, the feeling you have when you come in contact with it,” Hicks says.

Croatian artist Jagoda Buic’s 1967 “Fallen Angel” is a brown form suspended from a metal ring. It vaguely resembles a buoy or a space capsule parachuting into the sea. In Poland, which became a fiber powerhouse, Magdalena Abakanowicz wove her 12-foot-tall “Yellow Abakan” in 1968. Suspended from three thin wires, the tortilla shapes, with folds at the middle, ruggedly woven from autumn gold sisal, suggest a burlap religious cloak or a yurt or a vulva.

Porter also devotes space to the intersection of the modernist fascination with designs based on grids and the linear structures of weaving. “The grid is also intrinsic to the loom. You have the vertical lines of the warp and the horizontal lines of the weft,” Porter says.

Most of the art in the exhibit is abstract, but some pieces adopt shapes from nature—or perhaps mutant pods sprouting on alien landscapes. Francoise Grossen’s 20-foot-long “Inchworm” from 1971 looks beetle-ish, with pale knotted cords forming five humps and ropes running out from the sides like legs and coils at the end that suggest pincers or antennas. Though the artist downplays the resemblance. “Everybody can see what they want and maybe I went too far in naming it,” she says now.

In 1972, faculty and students in the groundbreaking Feminist Art Program at the California Institute of the Arts temporarily transformed a dilapidated Los Angeles house into an exhibition and performance space offering a bridal staircase, menstruation bathroom and dollhouse room.

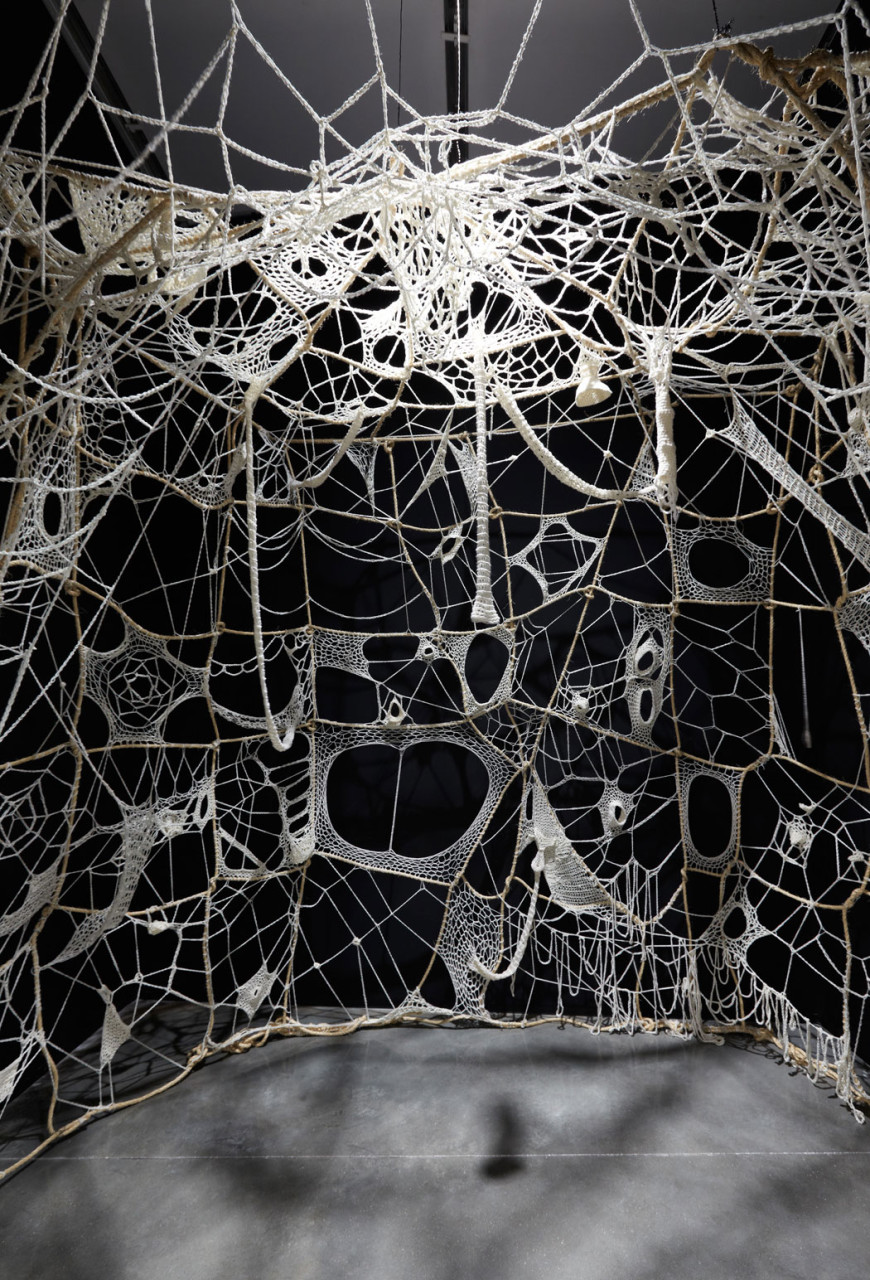

Student Faith Wilding—who is now based in Providence and had been influenced by Abakanowicz’s weavings when they were shown at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1971—turned one space into her “Womb Room” by painting the walls black and filling the space with a dome-shaped spiderweb of white yarn and rope with various dangling protuberances. It’s part shelter, part trap. (The version here was recreated in 1995 and is now known as “Crocheted Environment.”)

Porter writes that despite the fiber art’s efflorescence in the 1960s, it remained little noted by the fine art world or “relegated dismissively to the category of craftsman.” Lurking behind such categorizations were beliefs that fiber art wasn’t as good as painting or sculpture because it was traditionally the work of women, of the working class, of non-white folks. Feminist artists embraced techniques like crocheting in defiant opposition to this bigotry.

Porter, though, still gets caught up in old, curdled divisions between artists and artisans. When she calls fiber “art and craft,” she’s arguing that its falls into a new hybrid category that’s better than craft.

So what exactly is Porter’s definition of “fiber”? “Sculpture,” “scale,” “materiality,” “linear pliable element” and “softness” are some terms she mentions. “I wanted to think about how a tiny three-dimensional object like thread could be a giant sculpture.”

The objects here are woven, knotted, crocheted from thread or rope. Macramé is okay. But fabric, sewing, quilting and embroidery are out. No yarn bombing. Nothing you could wear. Nothing toy or doll-like. Porter leaves out the crafty revolution of the past couple decades exemplified by the Bazaar Bizarre hipster craft fair launched in Boston in 2001, the 2003 book “Stitch’n Bitch,” the establishment of the online craft powerhouse Etsy in 2005, and the founding of “Make” magazine in 2005 and its first Maker Faire in the Bay Area in 2006.

A hitch is that in doing so, the exhibit seems to again endorse the old—and mistaken—notion that craft is not as good, not as serious, not as important as fine art. How can Porter really revise entrenched histories if she buys into these dusty, exclusionary aesthetic hierarchies?

In “Fiber”’s version of history, the style basically disappears in the 1980s and ‘90s. Third wave feminism of the 1990s and the crafty revolution, though, sparked a revival by the 2000s.

Piotr Uklanski seems to tease the feminist legacy with his 2012 “Untitled (Femmage),” a 12-foot-tall abstracted, alien face with stringy hair, wrinkled and pimpled skin, pod eyes, and a mouth like a red vagina surrounded by curling black and brown hair-horns. Ernesto Neto uses fiber to create jungle gyms for you to enter into, like his 2012 “SoundWay,” a curvy, narrow hanging tent-corridor made of netting. Bells and seedpods along the bottom ring and rattle is you bump them while walking through.

Xenobia Bailey’s 1993-2009 “Sistah Paradise’s Great Wall of Fire Revival Tent” is a brightly hued conical tent with eyes above the doorway. It hints at ritual magic with an incantation along the bottom edge: “She protects me with her gaze streaming from a treasure house of abundant grace.”

The Bauhaus artists were thrilled by the new possibilities their machine age. But if you visit the Walter Gropius house operated by Historic New England in Lincoln, you find that the interior of his home was extensively furnished with rugs and furs and handcrafted dishes that soften the hard, industrial geometries of his 1938 modern design.

Today we’re still pursuing that balance between handmade and technology as the contemporary craft revival runs in parallel with our futuristic smart phones and smart bombs. People seek out craft’s deft skill and human flaws as a cozy, homey tonic to our wondrous technologies that we so passionately love/hate.

Greg Cook is co-founder of WBUR’s ARTery. Be his pal on Twitter @AestheticResear and the Facebook.

This article was originally published on October 01, 2014.