Advertisement

How Writer Celeste Ng Came To Love 'God With A Megaphone'

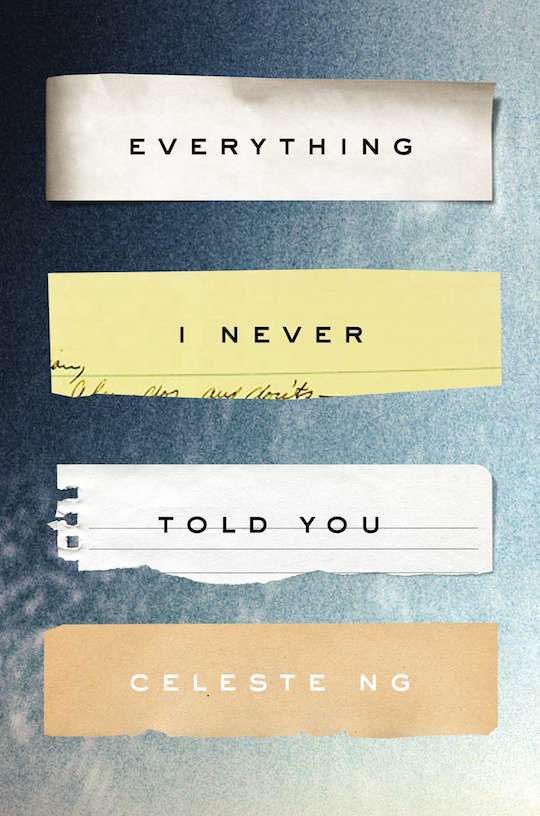

Celeste Ng’s recent novel “Everything I Never Told You” tells the story of a family unraveling in the wake of the mysterious drowning death of its favorite daughter. The book is a subtle and powerful exploration of grief that also tells the larger story of a biracial family (a Caucasian mother and Asian father) living in small-town Ohio in the 1970s.

I was struck by the ability of the novel to etch with crystalline clarity the forces holding a family in place and I asked Ng if she would let me peek behind the scenes of her writing process. Upstairs at Café Algiers in Harvard Square, surrounded by books and copies of old drafts, I listened as Ng dissected her struggles with the omniscient voice, a surprisingly tricky narrative voice that she realized she needed near the end of her novel.

The Problem

When Ng was rewriting the climatic scene of her novel, a confrontation between Nath, the brother of the family, and a neighbor he thinks is hiding something about his sister’s death, the little sister Hannah kept piping up to interject her viewpoint.

This intrusion went against the point of view rules Ng had established for the novel. The four family members had been taking turns telling the story and revealing their secrets, each section assiduously sticking to the narrator’s point of view until he or she passed the baton to the next. A blank line clearly signaled the switch in viewpoint.

On Saturday, October 25th at 4:45 p.m., Ng will appear on the "Fiction: Love and Loss" Panel at the Boston Book Festival. To find out more, visit here.

Ng was on the third draft and this structure had been a nagging problem for a while. To get each character’s reaction to certain events, she had to rehash it multiple times. At one point when the parents fight, we see it from the mom’s perspective but then have to wait many pages to see how the dad reacts. In a novel where the power of the story comes from the subtle shifts in how different characters react to the same events, this made for confusing reading.

So when Hannah kept butting into the climactic scene, Ng realized she needed to collapse all of the fragmented narratives into a single story and weave them together with an omniscient narrator.

Cue the scary music.

Advertisement

The omniscient, “all-knowing” point of view is associated with writers with booming, bossy voices like Tolstoy and Dickens, who migrate freely into the viewpoints of many characters, offering their opinions on the people and action.

“I thought of it as God with a megaphone, directing the characters,” Ng said. “It was uncomfortable for me to be that present in the story. I think one of the reasons that I like fiction versus nonfiction is that I myself can kind of disappear from the story. For an omniscient narrator, it feels like you have to put yourself back in.”

What She Read

To crack the code, she looked at other books that had successfully used the omniscient narrator: “The God of Small Things” by Arundhati Roy, “Amy and Isabelle” by Elizabeth Strout and “Evening Is the Whole Day” by Preeta Samarasan.

All of the books established the omniscient narrator right off the bat, she noticed, many of them starting with a God’s-eye point of view, especially those for which the setting was crucial to the story.

“Evening Is the Whole Day,” a novel set against the backdrop of civil unrest in Malaysia, begins with a description of the country as if seen from a helicopter and then zooms in slowly to the town level, the street, the houses — it is not until the bottom of the second page that we even meet the first character.

“What you look for as a reader is somebody who is going to take you and say, ‘C’mon, come into the story, I’m going to show you what there is to see. The guide who is going to tell you, ‘Pay attention over there,’ or, ‘Do you remember that other thing? Now watch!’”

The Solution

So it was back to Page 1.

At this point, the first line of the book was:

At first they don't know where Lydia had gone.

We are in the mother’s viewpoint, following her as she searches the house for her missing daughter, Lydia. We’re in the same confused state she is and each family member in turn tells his or her version of the morning. Laughing, Ng says, “No reader wants to sit through the same scene four times in a row, unless they’re radically different.”

Because the family was the setting in her novel, Ng recognized that she needed to quickly establish the four viewpoints, allowing the reader to understand that he or she would be seeing the story through each of the characters’ eyes.

So she cherry-picked the best parts and collapsed them into one scene – as it unfolds, we shift almost imperceptibly between each person’s point of view.

Most crucially, she changed the first line:

Lydia is dead. But they don't know this yet.

Not only did this line have more zing, it immediately changed the audience relationship to the family.

“We know where she is but the characters don’t know, so we’re immediately placed in a position where we can see a little farther than the characters,” said Ng. “It’s like we’re on a little stepstool.”

So while she’s not hovering above the scene in a helicopter, that extra height from the stepstool radically alters what Ng can do and say as a storyteller.

With the fight between Lydia’s mother and father that had originally played out fifteen pages apart, Ng’s new narration takes on a dagger-like point.

In the scene, which follows a visit from the police, the mother Marilyn is berating the father James both for shushing her and for accepting the police’s version of events, and we see his reaction immediately.

“I know how to think for myself, you know. Unlike some people, I don’t just kowtow to the police.”

In the blur of her fury, Marilyn doesn’t think twice about what she’s said. To James, though, the word rifles from his wife’s mouth and lodges deep in his chest. From those two syllables — kowtow-- explode bent-backed coolies in cone hats, pigtailed Chinamen with sandwiched palms.

In the original version, Ng said, “there was no narrator who could come in to say, ‘James hears something else,’ and so the reader just had to guess what James was thinking.” The omniscient narrator allowed her to swivel the camera around to his point of view.

Continuing, Ng takes the analogy one step farther, though with some reluctance.

“It’s sort of like in reality TV if you have two characters who are arguing and then it’ll cut away to Character A who’s in the little booth and she’ll go, ‘I was so mad at her because she was saying all these things to me,’ and it’ll cut away and you’ll see the other person’s side, and then you’ll go right back to the argument.

“Think about that versus Jerry Springer, where they’re just brawling. You’re not really sure who’s telling the truth or why this woman starting hitting this other woman, so there’s a lot that you as the audience have to do to figure that out.”

Once she made this change with the omniscient narrator, the whole story hung together and that fourth draft ended up being the final one. Ng said she became so enamored of the omniscient narrator that she’s sticking with it for her next novel.

You can see Ng’s third draft of Chapter 1 below:

And how it changed in the final draft:

Val Wang is the author of Beijing Bastard, coming Oct. 30. www.valwang.com