Advertisement

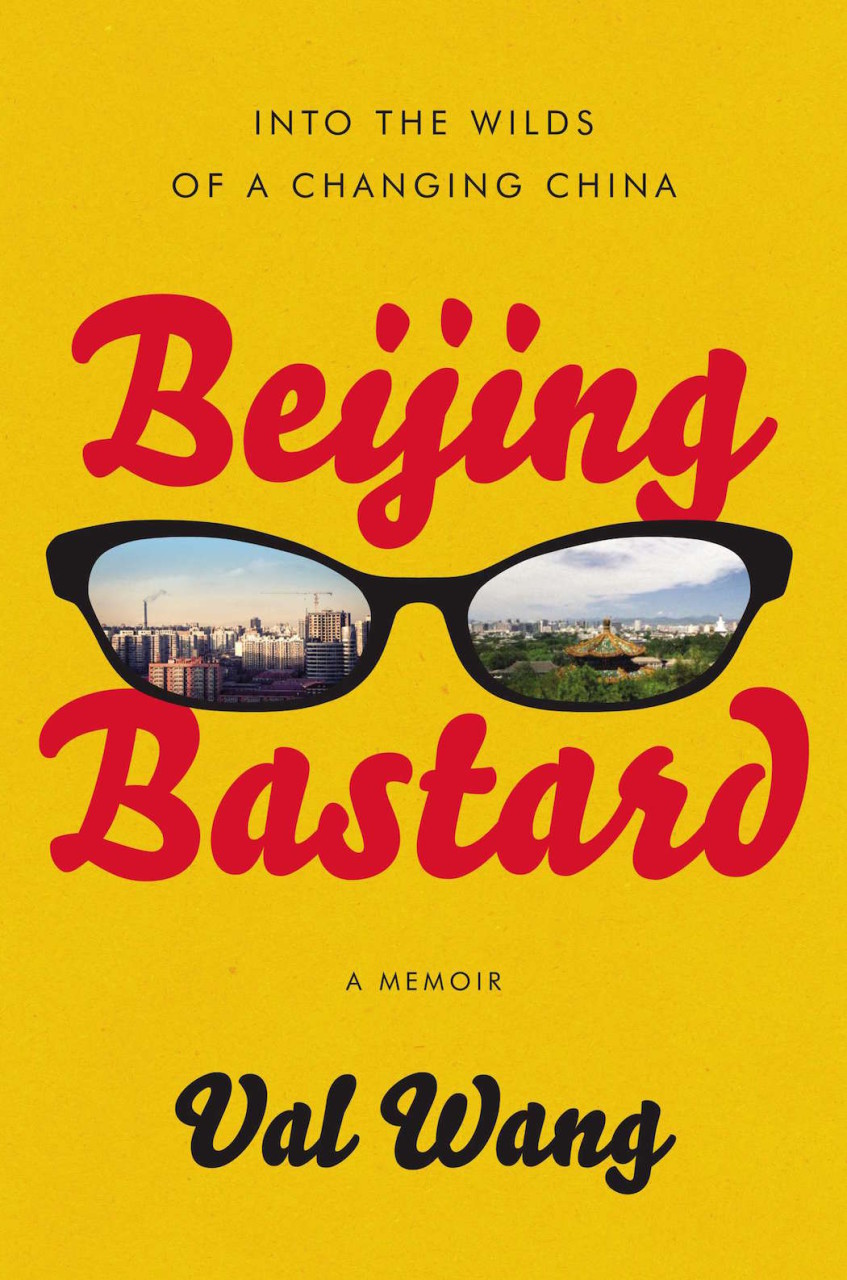

In 'Beijing Bastard,' Val Wang Looks At China Through New Eyes

The opening scene of “Beijing Bastard,” Val Wang’s wonderfully unreserved memoir, shows her and her father reading a picture book together. When she asks about a new word, “journey,” her father explains it as “a long trip.” The young Val is disappointed; she wants the mysterious-sounding word to mean something bigger. By the end of that book, though, she realizes it does — only this word describes how “you sail into uncharted waters searching for something you’ve seen with only your innermost eye.” Years after that conversation, Wang would leave the tight cocoon of her family and make her own remarkable journey.

Wang — a multimedia storyteller who resides in Boston (her interactive documentary, “Planet Takeout,” highlights Chinese takeout as “a cultural crossroads”) — was not raised to be an adventure heroine. The younger of two siblings in a high-achieving Chinese immigrant family, Wang hungered for her parents’ respect, but chafed at their non-negotiable rules. She and her friends were primed to be “nerdy, overachieving droids … marching through the Ivy Leagues into respectable professional careers.”

Their Washington, D.C., suburb had enough Chinese-American families to give Wang and her older brother “a nearly lethal dose” of Chinese culture: Chinese school, which she attended every Sunday from kindergarten through high school.

But Wang does not paint her childhood in monochromatic tones of constraint. She is in awe of her parents’ individual, treacherous voyages in 1949 from the new Communist China to the U.S. (where they met in New York City). Though she disliked the blandness of her surroundings, Wang understands that the “suburbs allowed my parents to create for the first time an orderly world that they had total control over.”

Family stories told by her parents and grandparents make her ancestral home feel close at hand. But the vast distance between the two countries — in miles, politics, culture — makes China feel unreachable to her.

After graduating from Williams College and heading to New York City, Wang feels that her path is too well-trod. The only way to really know what she wants from life is to radically expand the space between herself, her family and her group of friends. Her choice of destination makes “Beijing Bastard” a distinctive memoir: at once a pioneer coming-of-age tale and a discovery of family roots, set in a China that is quickly shedding the old century and dramatically donning the new.

A book about a journey can cast a mesmerizing spell; why an author leaves all that’s familiar is as compelling as the new landscapes explored. We armchair travelers can thrill to the discoveries, and be inspired by the fortitude needed to complete the passage, all from the coziness of our own well-known locale.

By the time she arrives in Beijing, Wang, in her early 20s, is an engaging blend of resolute courage and wavering self-confidence. She lands a full-time writing job at an English-language magazine, and after a brief stay with relatives, finds a one-bedroom apartment in a fringe neighborhood, preferring funky shops and dodgy characters to safer, more sterile environs.

Wang’s dry wit and sense of history can make a mundane activity glint with the promise of a hidden, bigger tale. With pacing that only occasionally sputters, Wang unearths narrative treasure in kitchen plumbing problems, phone calls with her parents (riddled with the doctor/lawyer/PhD triumphs of her peers), and the endless, and endlessly fraught, quest for a capable hairdresser.

A Chinese-American in Beijing at the turn of this century, Wang watches buildings of the new Beijing rise into the always-polluted skies, and bears witness as the old Beijing, with its courtyard houses and street vendors, disappears under the weight of modernization — at first for the 50th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China in 1999, and then for the 2008 Olympics. With so much change, contradictions abound. It is a Communist country with low wages, but the roads are “filled with Mercedes-Benzes and the restaurants bursting with fat men.”

Perhaps most dissonant of all, Wang always carries within her the traditional world of her family, even as she attends subversive art exhibits or drinks in underground bars with her new friends. Chapter titles convey the concentric circles of her inner and outer life: “Seeks Trouble for Oneself,” “To Fill in the Blanks” and “The Outlaws are the Ones Who Become Moral.”

Staff feature writer by day, she longs to make indie documentaries. (Wang has also freelanced for WBUR.) Which brings us to the book’s title. It’s based on the spark that ignited her odyssey, the groundbreaking indie film “Beijing Bastards” by Zhang Yuan. Recorded documentary style with a handheld camera, the film followed the travails of a fictional group of young Beijing artists in the early ‘90s. It was everything Wang’s ordered life was not.

She begins to meet and write about some of her movie heroes. She musters the courage to embark on her own project, a film about a family struggling to keep alive the traditional art of Peking Opera, in a city that now wants to only look forward, not back. As Wang becomes bolder in her art and her life, she can also forge a deeper bond with her parents.

Somewhere in the middle of the story, there is a small scene that is memorable as much for its relaxed tone as its details. When a friend visits from the U.S., Wang, her old friend and a local friend hike “a crumbling section of the Great Wall and [sleep] out on a parapet.” It’s a simple point in her Beijing life, moving now effortlessly through the old and new: evocative, fleeting, lovely.