Advertisement

MIT Shows How A Tree Can Be A Documentary

MIT has long been at the forefront of fostering and tracking the creation of new documentary forms. The 2012 addition of the Open Documentary Lab to MIT’s nine other research labs affiliated with Comparative Media Studies has put its graduate students, practitioners and faculty back in the documentary spotlight.

A deceptively simple student project, ListenTree, which has its roots in multiple labs including Open Doc Lab and the well-established Media Lab, serves as both example and metaphor for what documentary means at MIT at this moment.

So what’s a ListenTree? Conceived by Media Arts and Science graduate students Edwina Portocarrero and Gershon Dublon, it’s a tree that conducts sound vibration from a hidden, remote device. Passersby must press their ears to any part of the trunk or branches to hear the broadcast by way of bone conduction.

In addition to being on exhibit in the entrance of MIT Museum through Dec. 31, its creators have been invited to present ListenTrees in Mexico City for Day of the Dead festivities, and then in Montreal for the all-documentary RIDM Film Festival, held Nov. 12-23. (Full disclosure, I am teaching a class for Montserrat College of Art that will travel to RIDM.)

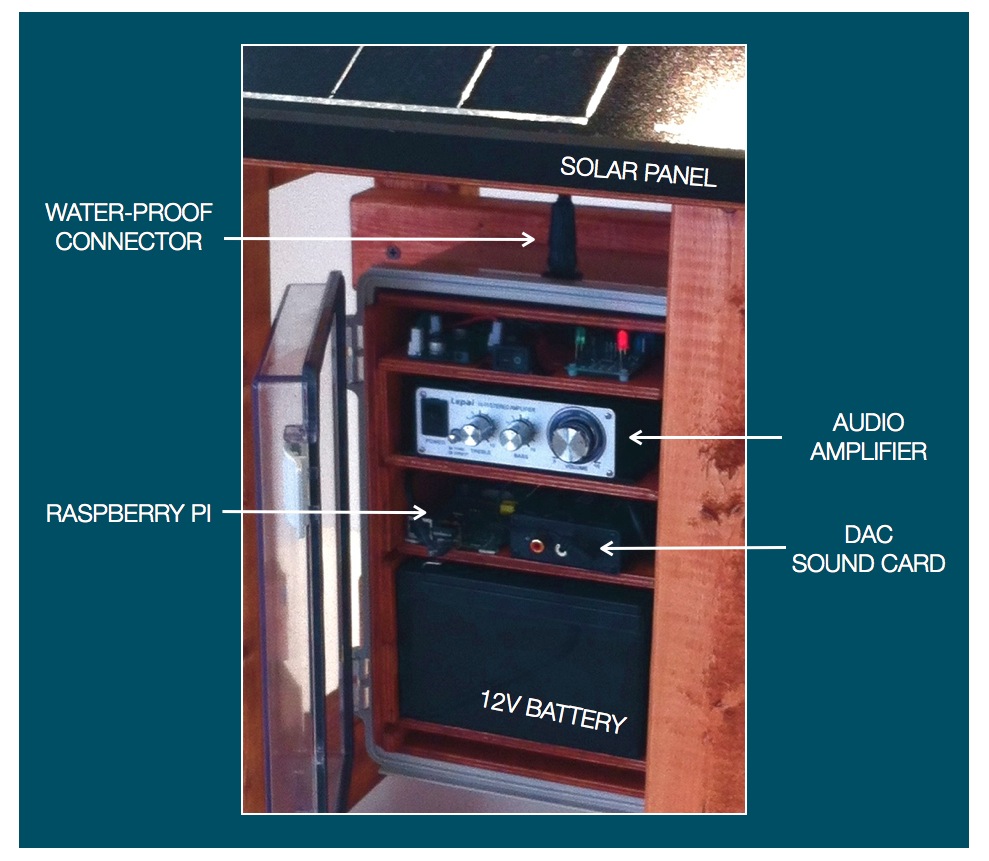

At first, Portocarrero and Dublon weren’t sure their idea would work. They considered various conduits and chose trees because of their mythical status and enviro-friendly ubiquity. They tested their concept by rigging up a few on campus, guerilla style, playing sounds recorded from a farm-to-wetland restoration effort at Tidmarsh Farms near Plymouth (part of the Living Observatory Project founded by former MIT professor and documentary filmmaker Glorianna Davenport). These trees ran on solar power and a silicone rubber-encased transducer screwed into the tree roots. That’s the system they are re-purposing in projects beyond U.S. borders.

In an interview earlier this fall, the creators pointed out that ListenTree’s easily reproduced technology is also highly adaptable. The audio can be anything from a string quartet with four trees playing individual parts to distinct roles in a play. In Portocarrero’s hometown of Mexico City, a circle of six trees at the National Center for the Arts will be part of traditional Day of the Dead celebrations. According to Portocarrero, they will likely stream poems by some of Mexico's foremost poets such as Efrain Huerta, Octavio Paz, Nezahuacoyotl or Jaime Sabines, and possibly some calaveras (funny epitaphs by which the dead are remembered).

In Montreal, students from University of Quebec-Montreal (UQAM) will program the audio to play through a stand of native maples. The exhibit is part of RIDM’s DocUX track, the interactive strand of a festival known for toeing the edge of what qualifies as documentary.

Because ListenTrees have no moving images, it begs the question: is this documentary? According to Sarah Wolozin, director of the MIT Open Doc Lab who has been following the ListenTree project and suggested it for RIDM, absolutely. “When we look at new documentary forms,” she explained, “we purposefully want it broad,” adding that as technology evolves and new tools become available, those tools are inevitably used to document.

Advertisement

“So if sensors are tools for communicating—both taking and giving information,” then the question Wolozin asks is, “How do you tell a documentary with sensors?”

Portocarrero and Dublon’s design has near infinite answers to her question. For example, simply adding a microphone to ListenTree’s audio device typically housed in a weather-resistant shelter could allow passersby to be both (or either) creator and/or receiver. ListenTrees could be networked so that visitors at MIT Museum, in Mexico City and Montreal could communicate, real-time.

Incorporating moving images wouldn’t be all that difficult, either, it’s just not part of the original concept. What’s more important to what Wolozin referred to as “new documentary,” is its unrestrained use, and for Portocarrero and Dublon, its capacity for local, organic application.

“New, interactive, participatory docs are taking from the software movement,” said Wolozin, in affirmation of the lab’s affinity with open source thinking. Whether data or source codes, the idea is to share and share alike, and to do so without profit, hence the name “Open” Doc Lab. Part of that ethic encompasses non-linear projects—documentaries that remain open to gather data, possibly without end—or as she explained, “You put them out earlier in process before they are done.” A useful list of what makes a “new documentary” based on a past event hosted by Open Doc Lab can be found here.

In addition to hosting cutting edge filmmakers for one-time events or longer-term fellowships, Open Doc Lab partners with other leaders in the “new” documentary field such as the IDFA Doc Lab to create Moments of Innovation, an interactive tool that defines and contextualizes documentary; with Sundance Film Festival to provide press coverage of its New Frontier section; with Tribeca Film Festival to convene a working group to define and measure impact in new documentary; or with festivals like RIDM or agencies like the National Film Board of Canada. It’s also tracking the field’s growth and progress in an online, dynamic database, _docubase.

William Uricchio, MIT professor of Comparative Media Studies and principle investigator of MIT’s Open Doc Lab and Game Labs, explained the benefit of engaging with the independent film industry as an educational institution: “We don’t compete. The festival people are colleagues and friends fighting over which is the top festival, [whereas] we provide a neutral space or platform… here, we can kick it up a level and talk about ideas.”

The external efforts dovetail with the Lab’s—and the school’s—motto to be both mens et manus (mind and hand) to its students, and to positively impact the community at large. Wolozin joked that she’s a “Robin Hood of knowledge.” As it stands, that community knows no border.

Erin Trahan edits The Independent and is teaching an adult education course for Montserrat College of Art that will travel to Montreal’s RIDM Film Festival this November.