Advertisement

How A Jilted Mom, A Former Nun And A Shattered Childhood Inspired ‘Madeline’

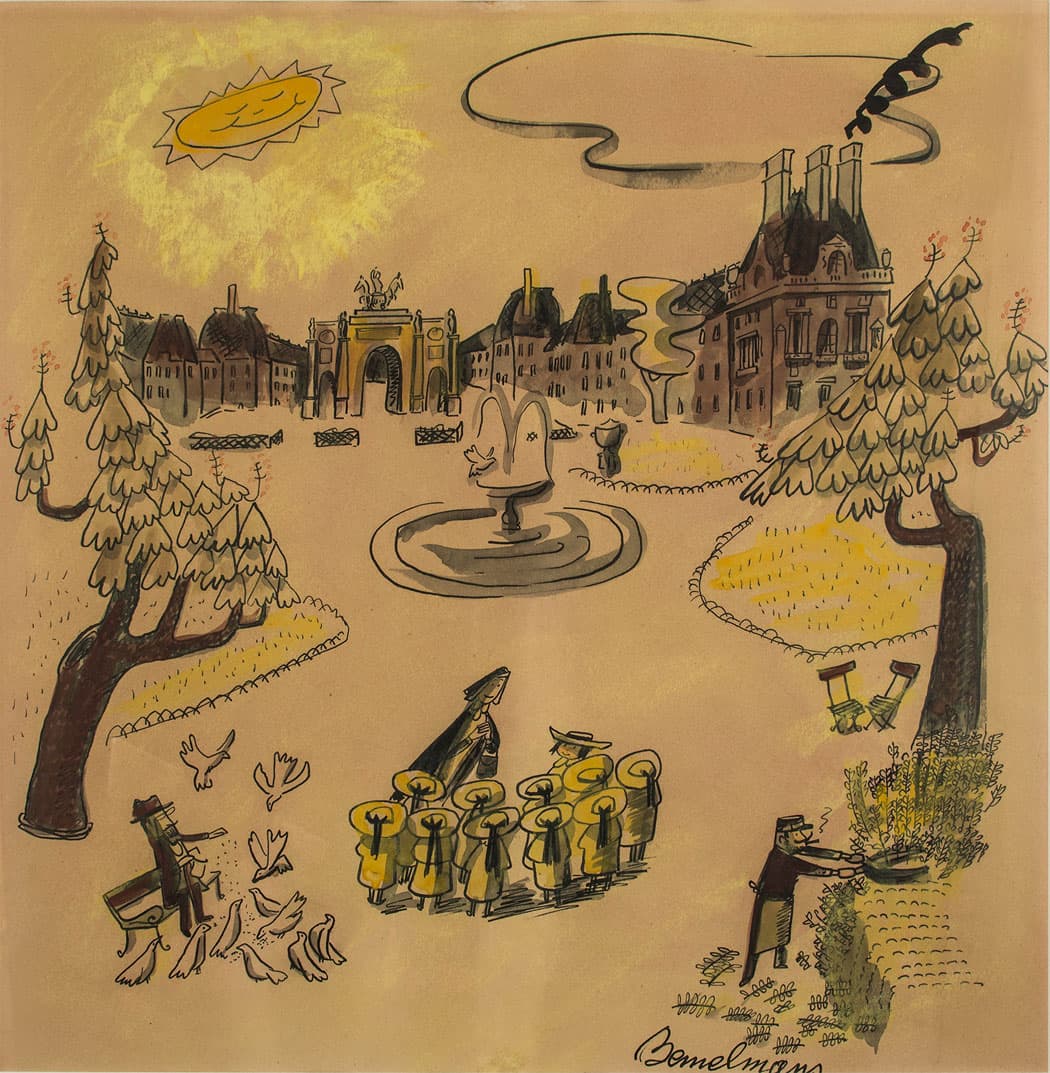

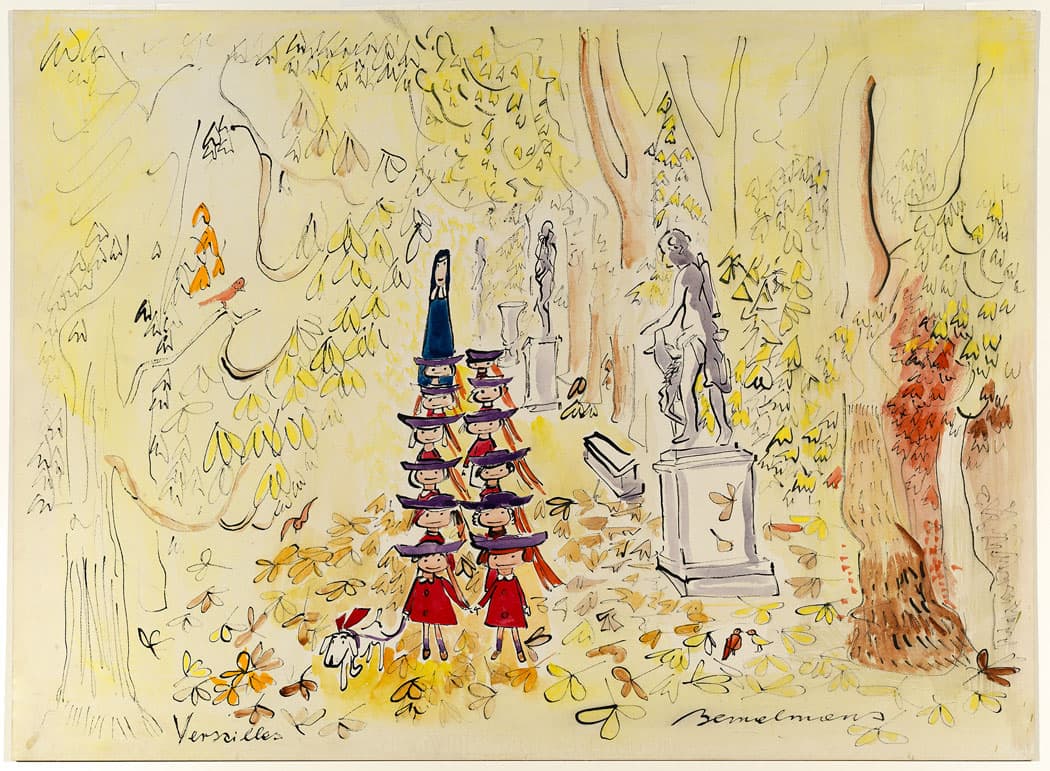

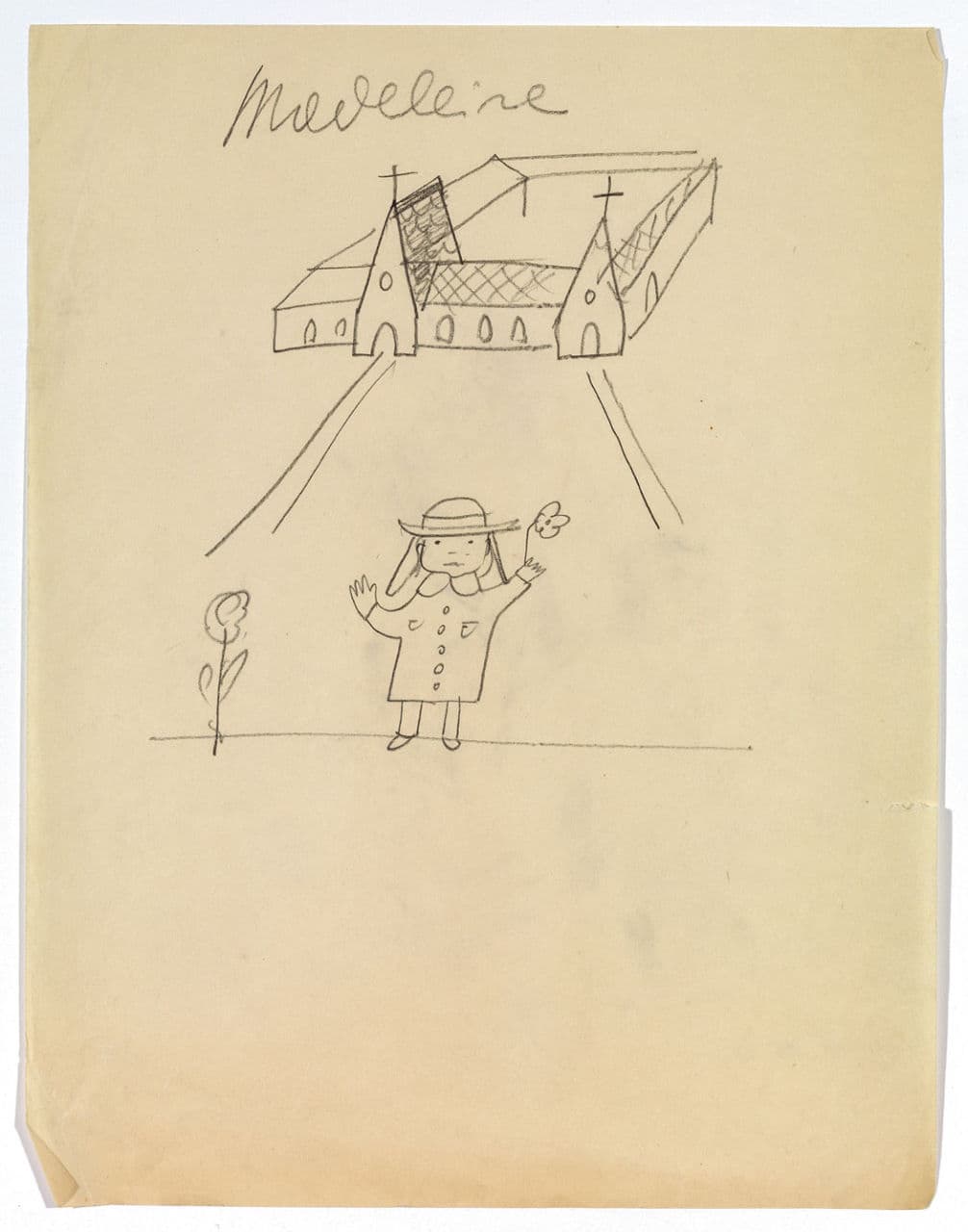

“In an old house in Paris that was covered with vines lived 12 little girls in two straight lines. … The smallest one was Madeline,” begins Ludwig Bemelmans' landmark 1939 children’s book.

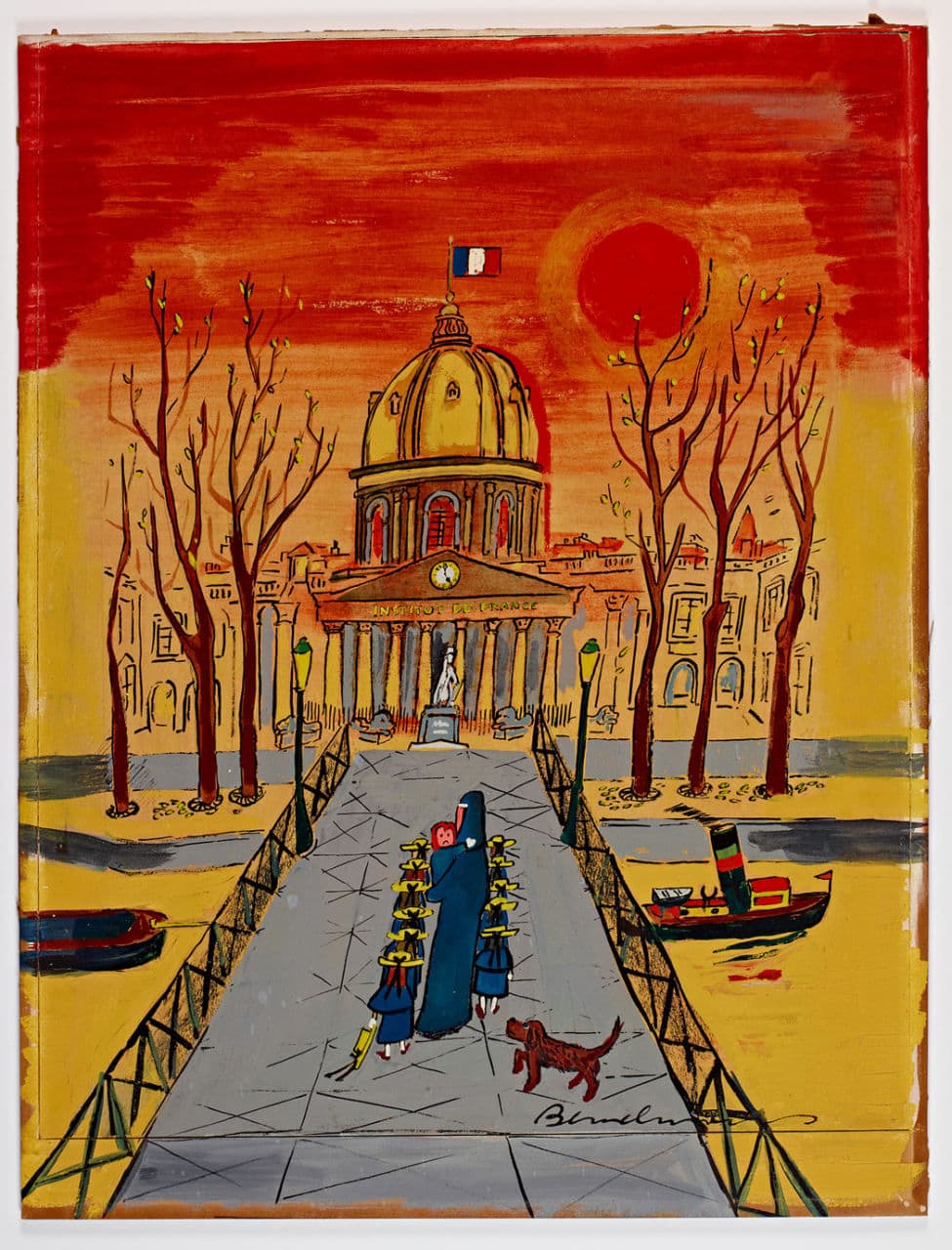

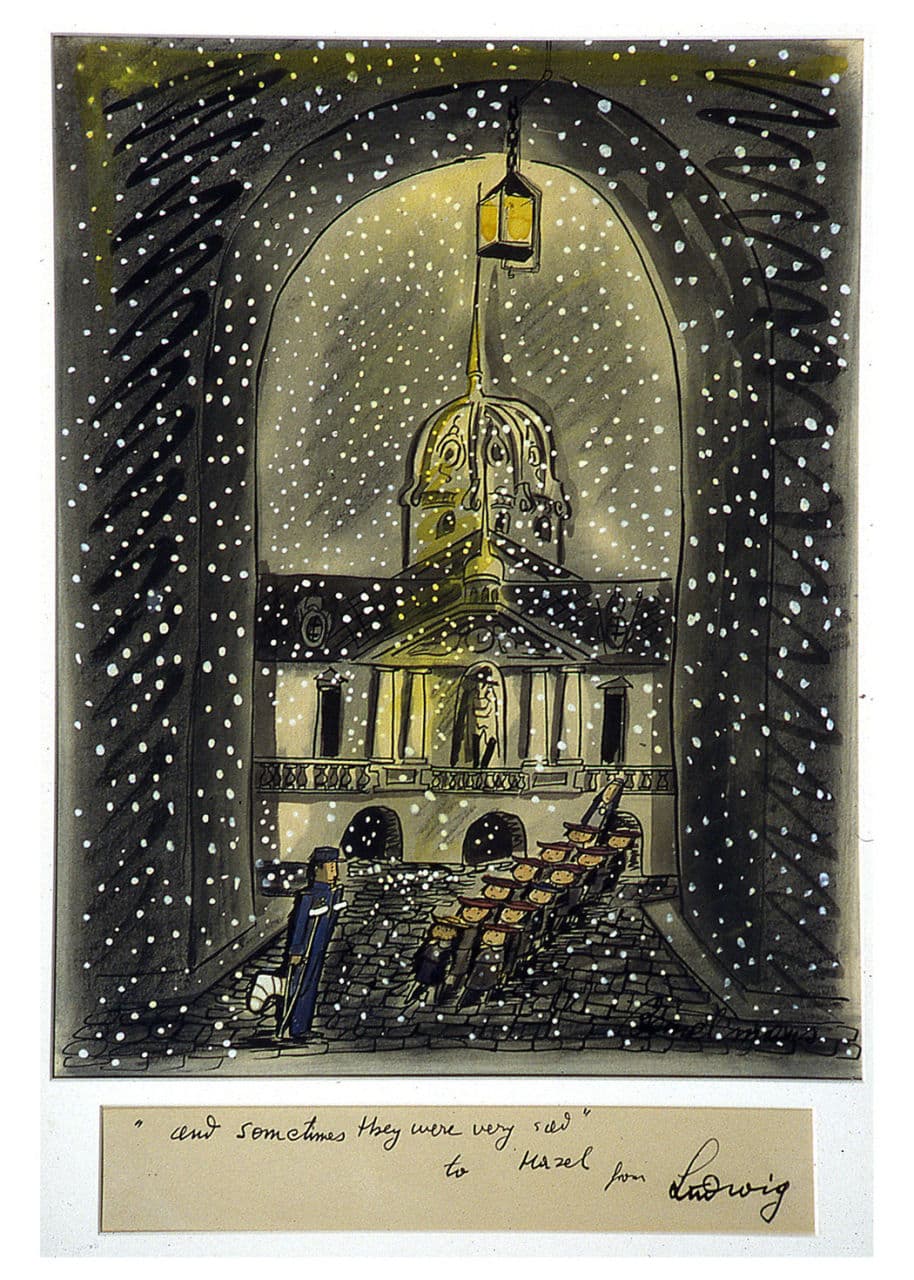

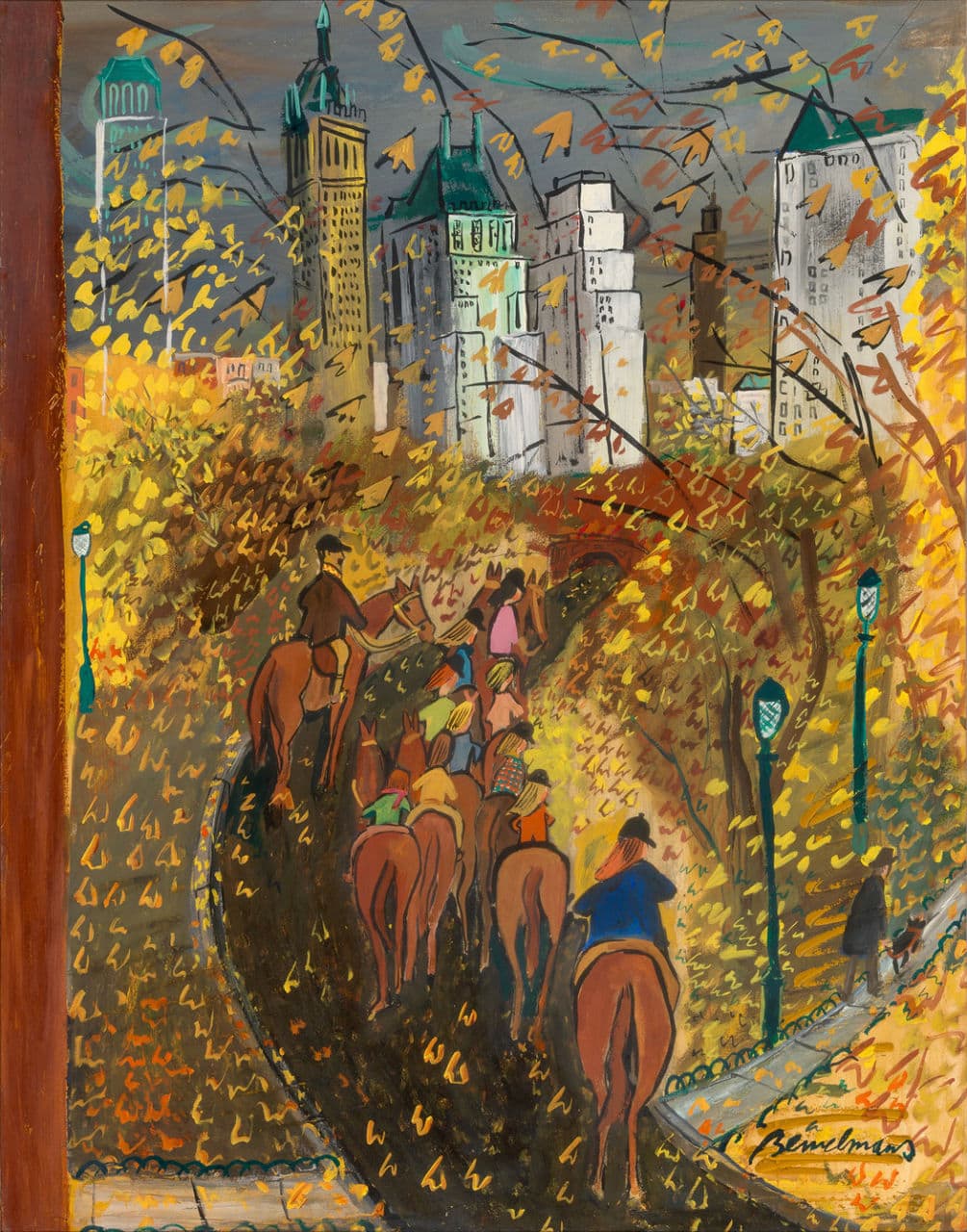

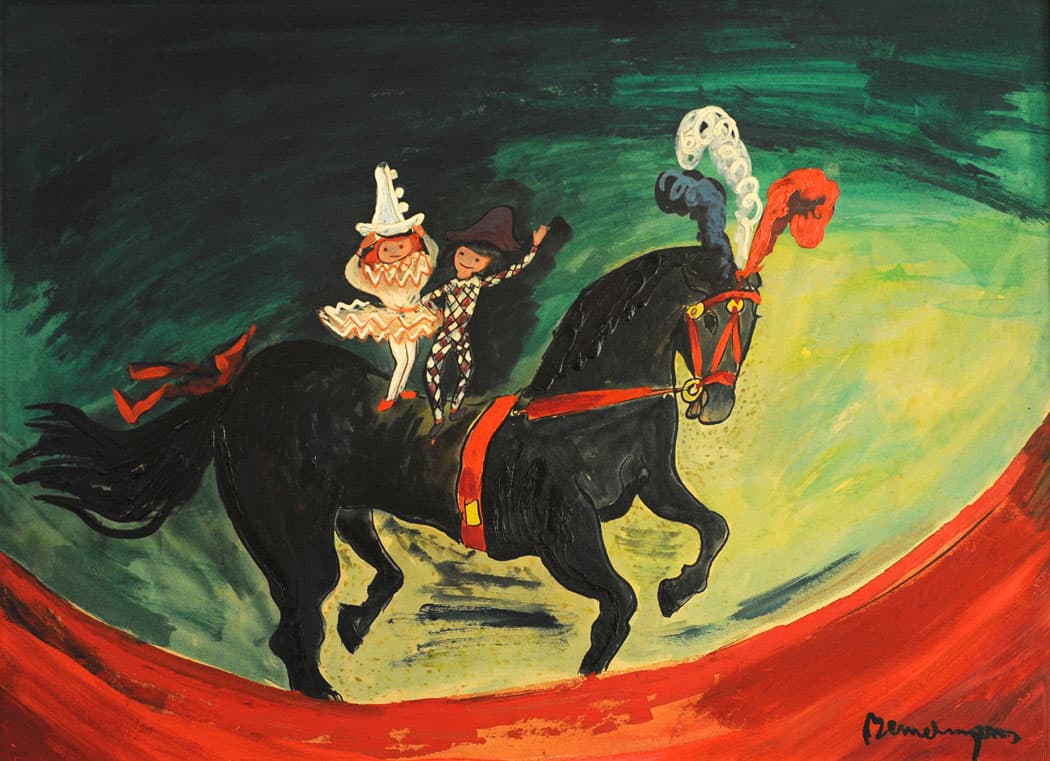

“Madeline,” as she appears in the picture books, is a plucky lass, unafraid of mice or snarling tigers, who likes to dance precariously along the railings of bridges as she goes out on expeditions across glamorous Paris. Part of the stories’ great charm is the comforting fantasy that nothing can go wrong—or, rather, anything that goes wrong can be easily remedied. A sick appendix, a fall into a river, a menacing neighbor, an inconvenient old horse, circus folk who sew you up in a lion’s skin? No problem.

Bemelmans (1898-1962) styled himself as a carefree bon vivant. But the inspirations for ‘Madeline,” which was named a Caldecott Honor book (a runner up to the top Caldecott Medal prize for American picture books), came from things that went wrong—his jilted mother, a hospital stay, a former nun, his own shattered youth.

“It was what he’d like his childhood to have been like,” explains Jane Bayard Curley, a New York curator who organized the exhibition “Madeline at 75: The Art of Ludwig Bemelmans” for the Eric Carle Museum in Amherst, where the show runs through Feb. 22. It’s a dream of childhood with no classrooms and no parents, a childhood all of lovely city adventures. “He was a guy who took all his lemons and made lemonade. This is what ‘Madeline’ is all about. He’s repairing his childhood.”

When Bemelmans was 6, his parents’ marriage broke up. His father ran off with another woman, leaving Bemelans’s mother as well as his beloved governess—whom he called Gazelle because he couldn’t pronounce mademoiselle—pregnant. (Curley says the governess eventually took her own life.) His early, idyllic years spent around the hotel his father ran in the Tyrol Mountains of Gmunden, Austria, came to an abrupt end as his mother bolted back to her family in her native Germany and “tried to erase all traces of his Gallic childhood.”

Bemelmans did not take it well, getting in trouble at school, and eventually quitting his studies at age 12. Mom sent him to live with an aunt and uncle on his father’s side, who ran hotels, and gave him a tryout at one after another, all unsuccessful.

Finally, Curley says, “He shot a waiter. He was given a choice: either go to reform school in Germany—he would have ended up in a trench somewhere in World War I—or go to America. And he chose America.”

Bemelmans imagined the United States as Disneyland—he later sketched a dream of Manhattan with train tracks running across the tops of skyscrapers like rollercoasters and Native Americans paddling about the harbor in canoes. But when the 16-year-old’s ship docked at New York on Christmas Eve 1914, his father, now a New York jeweler, failed to turn up to meet him.

“He was very much like his father, although they did not get on at all. He was also a traveler and a womanizer,” Curley says. “He tried to live with his father and it didn’t really work out.”

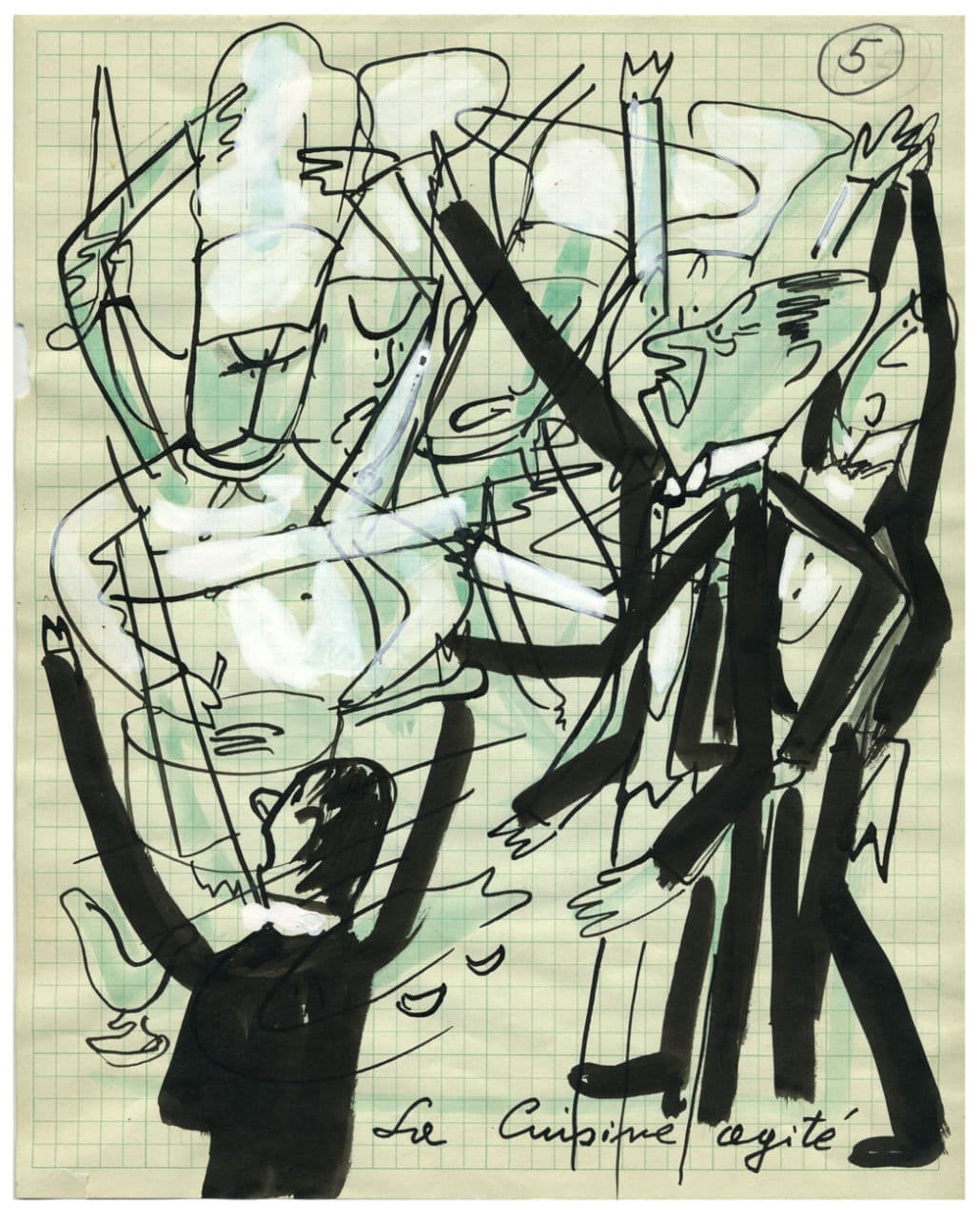

Instead, Bemelmans found sanctuary in the employ of the Ritz-Carlton hotel in New York, where over the next 15 years where he rose to become assistant manager of the banquet department. They allowed him to use the ballroom as his studio. And he crashed in William Randolph Hearst’s suite when the newspaper baron was off in California.

“Hotels became his family,” Curley says. “That’s where he grew up, that’s where he got his education. That was his chosen tribe.”

When World War I arrived, he joined the U.S. Army in 1917, teaching bayonet drill in upstate New York, then working in a hospital for shell-shocked veterans. There, Curley says, the 17-year-old “had a nervous breakdown. He was all alone. He wanted to kill himself. … He was terrified of failing. The things that kept him alive were what he called his ‘islands of security,’ these pictures in his mind, happy moments from his childhood.” And he drew. “I have started to think in pictures,” he wrote, “and make myself several scenes to which I can escape instantly when the danger appears.”

After the war, he returned to the security of the Ritz. He tried becoming a newspaper cartoonist in 1926 without success. He left the hotel in July 1929, and rented a Greenwich Village studio in hopes of becoming a full-time artist, but had to return to work at The Ritz three months later blaming the Great Depression. “He had grander ambitions,” Curley says, "than to work in a hotel all his life."

Madeline’s first published appearance was as a minor character in Bemelamans's second children’s book, “The Golden Basket,” which appeared in 1936 and won a Newbury Honor for distinguished children’s literature. Actually, Madeline first appeared in a mural he painted inside a Long Island tavern, Curley says. The character’s name was at first spelled like the name of his second wife, Madeleine Freund, with whom he’d eloped two years earlier. She was a former nun (“a priest groped her,” Curley says) who was trying out to be an artist’s model when they were introduced.

“That was a marriage of oil and champagne,” Curley says. “She was an austere, intellectual person who really, really cared about animal rights. … He was a bon-vivant, totally self-educated.” Still, the marriage would last nearly three decades, including surviving his affairs. “Oh, God, did he stray, but they had an agreement. … I think he kept his straying far away from her, but they stayed together.”

So Madeleine—called Mimi—was one inspiration for Madeline. Another was Bemelmans's mother. “She would tell me stories about her own childhood—of how alone she had been as a little girl and how she was shipped off to a convent school in Alotting, which was run by nuns of an order known as the ‘Englische Fraulein,’” he wrote in “Tell Them It Was Wonderful,” which was posthumously published in 1985. “She described the life there—how the girls slept in little beds that stood in two rows and how they went walking in two straight lines, all dressed alike. She was happier there than at home, for her parents never had any time for her.”

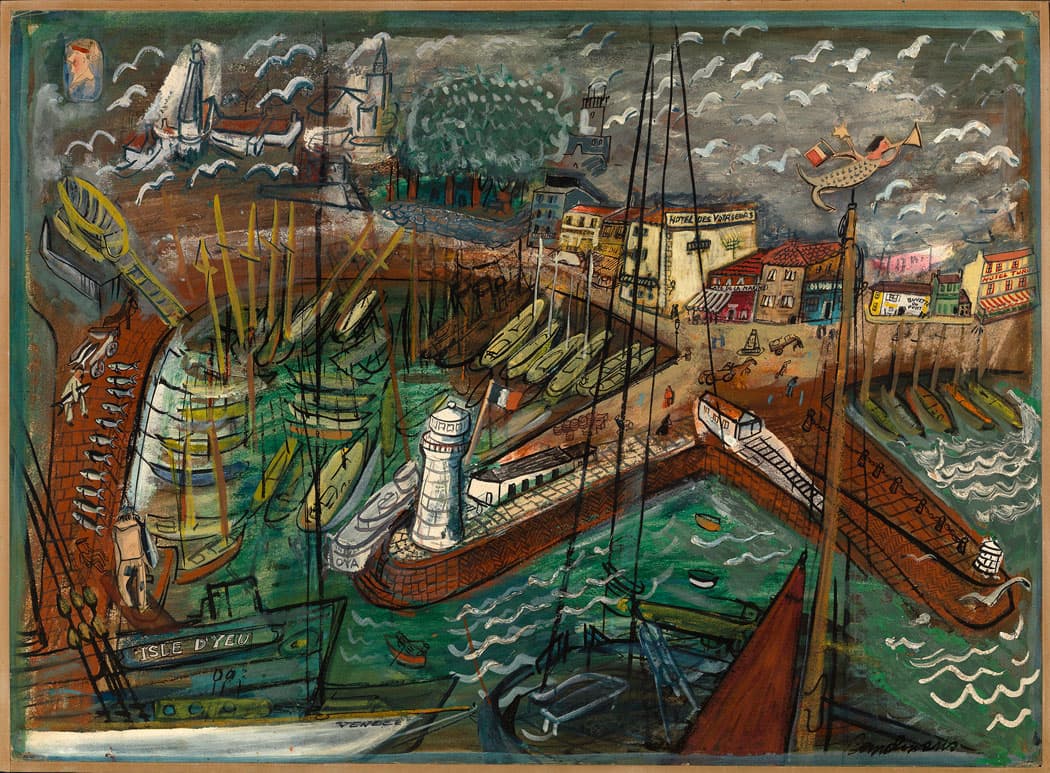

During a 1938 trip to France with Mimi and their 2-year-old daughter Barbara (another inspiration for Madeline), Bemelmans landed in a hospital at Ile d’Yeu after a collision between his bicycle and a car. Laying in his hospital bed, he stared at a crack in the ceiling that he thought resembled a rabbit. A girl in the next room was having her appendix out. He returned to the United States and when “Madeline” was published the following year, there she was in the hospital with a bum appendix and staring at a ceiling crack that “had the habit of sometimes looking like a rabbit.”

“Yes, his mother went to a convent school. … And his wife started out as a nun and then switched careers to be an artist’s model,” Curley says. But “it’s not just his story straight.”

Bemelmans took these inspirations and cut them up and stirred them around and composted them. For example, despite her appearance, Miss Clavel, who oversees Madeline’s posh boarding school (or whatever it is; it’s never really explained) “is not a nun,” Curley says. “She is in fact his Gazelle, his French governess” dressed in the severe style of Bemelmans' childhood.

“He polished that story and he polished that story,” Curley says, “until it became quite beautiful.”

By the time "Madeline" was published, Bemelmans’ career as an artist and author was taking off. He wrote and illustrated articles for The New Yorker, Town & Country, Vogue. “As he got older, when he got in trouble, he’d turn around and write about it in a funny and rueful way,” Curley says. “He was good at taking his troubles, his mistakes, and making them amusing to people.”

Bemelmans painted more than 30 covers for The New Yorker magazine. He drafted illustrations for Jell-O, lard, candy bars. He painted murals in hotels and bars. He was a screenwriter at MGM in Hollywood during World War II—apparently his only film to make it into theaters was a 1945 Fred Astaire flick called “Yolanda and the Thief.”

“He was a charmer and a flirt and a bad boy,” Curley says. He collected famous friends—or at least acquaintances—from royalty to director Alfred Hitchcock to actor Joseph Cotten, she adds.

Bemelmans published nine books for grown-ups, including four novels, in the 1940s. “His grown-up stuff was more topical and it was more ephemeral,” Curley says. “His novels are very dark. If you want to know who Bemelmans was as a grown-up and not-so-charming bon-vivant, read those.”

For all his output, Curley says, “He knew that Madeline was his legacy.” The second book, “Madeline’s Rescue,” was published in 1953 and won the Caldecott Medal. He mapped out a trajectory for the series—and would publish three more before he died. “He knew that that was an empire.”

“The reason that the children’s stuff goes on is he struck a cord with Madeline,” Curley says. She’s a loveable scamp, she bucks authority, she runs off with the circus, she flaunts her scars. “She is an everygirl. She is an intrepid girl.” No matter her troubles, she seems to just shrug them off, and everything turns out all right in the end.

Greg Cook, co-founder of WBUR's ARTery, is a want-to-be bon vivant. Join him on his expeditions across glamorous Massachusetts on Twitter @AestheticResear or the Facebook,