Advertisement

'Albatross' Fleshes Out The Details Of Coleridge's Classic Poem

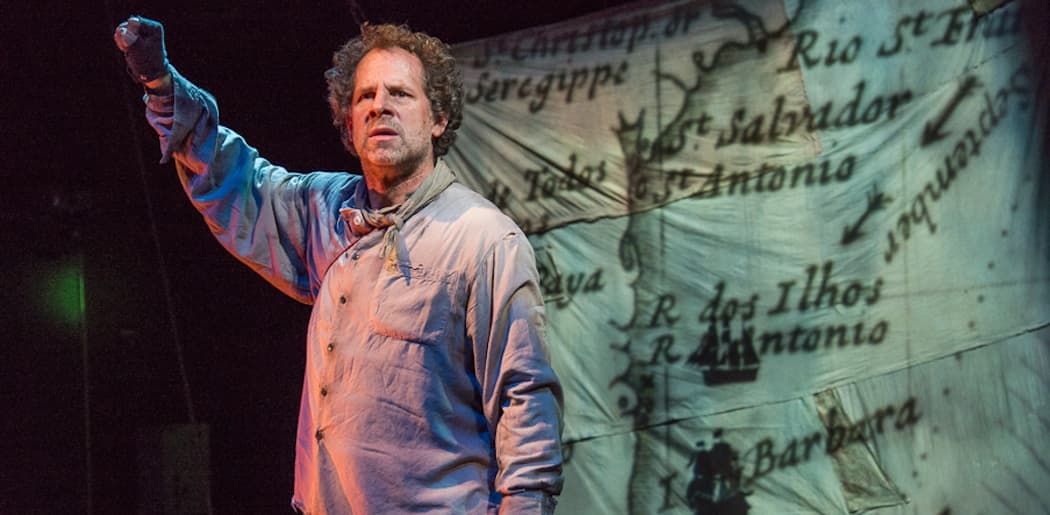

The Poets' Theatre, partnering with the New Repertory Theatre, is remounting "Albatross" at the Charles Mosesian Theater in Watertown from May 21-24, with a few minor changes to speed up the action. The production recently won two Elliot Norton Awards: Outstanding Production for a Small Theater and Outstanding Solo Performance (applauding Benjamin Evett as the Mariner). This piece originally ran in February.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- The Poets’ Theatre has a long and distinguished history of celebrating the vitality of language and poetry. Its founding, in 1950, included luminaries such as Edward Gorey, William Carlos Williams and Thornton Wilder; in the time since then, the theater has introduced seminal works such as Dylan Thomas’ “Under Milk Wood,” which the poet himself read publicly in 1953. (This incarnation of The Poets’ Theatre, its third, started off with a “Centennial Celebration” of Thomas, staging “Under Milk Wood” at Sanders Theatre last September.)

The theater's current production, "Albatross" (Feb. 13-March 1, The Jackie Liebergott Black Box at Emerson College's Paramount Center) is a full-length one-man show based on Samuel Taylor Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner." The poem itself is a work in six parts, but its total length is hardly epic. To flesh out the poem, "Albatross" writers Matthew Spangler and Benjamin Evett have asked themselves hard, essential questions about the Mariner. Who is he? What elements and events of his life led to his being aboard a ship whose journey to the southern polar region culminates in the fateful crossbow shooting of an albatross, and the subsequent rousing of supernatural forces?

“Albatross” is, in a way, a prequel to “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner”—though, in this case, the prequel supports and incorporates the original story. The elements Spangler and Evett have invented feel analogous to Coleridge’s poem, not in style so much as in theme. The narrative is jocular and dramatic, scintillating and vernacular by turns, but the events leading to the poem’s familiar incidents feel foundational to a modern take on the story.

This modernization starts with the way in which the writers give the story concrete locations and dates, positing that the Mariner resided in the port city of Bristol, England, and, in the year 1720, was shanghaied into the service of a tough privateer. We’re also given telling details about the Mariner's early origins—that is, where he comes from, who he is and what his life is like.

Other characters from the poem have dimension, too (the hermit who appears near the end of Coleridge’s original has a small part in the events leading up to the Mariner’s “conscription”), while newly invented characters round out the play, providing comic relief, the occasional note of treachery and poignant counter-balance to the Mariner’s moments of ruthlessness in his struggle for survival. In one nicely realized pun, the Mariner dismisses his crewmates as “fair weather friends" who alternately accuse and support him, depending on how they perceive his actions to have affected the ship’s fortunes.

"Albatross" offers us as much history as it does poetry, and as much earthy expression as transcendence of language. Evett, who not only co-wrote the play but takes on the role of the central character, plays the Mariner as salty as a sailor should be, his monologue brisk and peppered with profanity. At the same time, though, he proves to be more than just a product of his line of work and era—he’s familiar enough with our modern world to let fly with critiques concerning environmental degradation, smartphones and GPS.

Advertisement

In the play’s opening moments, the Mariner addresses the audience in Italian, then Russian, and then in something that sounds like Mandarin, before seemingly discovering that he’s in Boston and can stick to English. (His own native tongue, he observes—though with stronger language and in an Irish brogue.) This mashup of languages is a wonderful way to start the show, reminding us of the necessity and inherent difficulty in communicating all the aspects and layers that poets strive to master. It also dovetails nicely with the play’s suggestion that part of the Mariner’s penance is to live forever, plying his trade on the seas and telling the tale of his misdeeds to each new generation.

Evett’s performance is spellbinding, Rick Lombardo’s direction is dynamic and focused, and the finely attuned production design serves as a living argument for the poetic possibilities of the theatrical form. Set designer Cristina Todesco, who so often creates detailed and highly specific environments, designs a space for wide-open possibilities here. At first, there’s nothing but a number of ropes hanging down, plus a few props. But, as the Mariner introduces himself and sets the scene in our imagination, painting the time and place with his words, he unpacks raggedly improvisational sails from a trunk and rigs them up. The sails soon become the screens onto which Garrett Herzig’s projections play out, whether cozy and slightly surreal (cartoonish looking lanterns, warm and glowing), or animated and menacing (ocean swells, heaving waves, lashing torrents of rain).

Frances McSherry’s costume echoes the worn, improvisational look of those ragged sails: she’s dressed Evett in threadbare finery—layers of it—with some garments also suggesting the passage of decades. The total effect is one of antiquity that wouldn’t look too out of place in a contemporary setting. Rick Lombardo’s sound design meshes well with the visuals, ranging from the ghostly and distant to the urgently immediate. Franklin Meissner, Jr. paints not only with light (often in coolly aquatic hues of green and blue), but also with shadow. In the end, this play, though created for the black box venue, succeeds in opening audience imagination to a wider, wilder world.

Kilian Melloy has reviewed film and theater for a number of publications, including EDGE Boston and the Cambridge Chronicle. He is a member of the Boston Theater Critics Association and the Boston Online Film Critics Association.

This article was originally published on February 19, 2015.