Advertisement

Downright Subversive — Thinking About 'The Man In The Gray Flannel Suit'

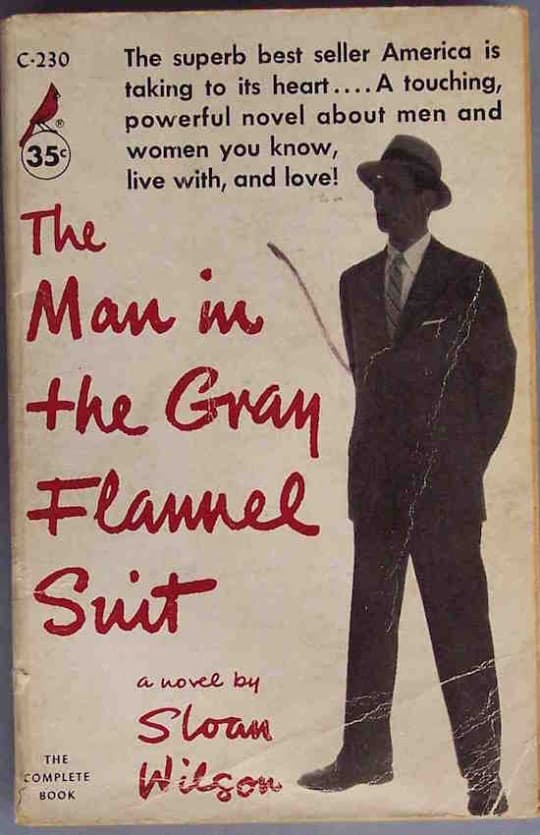

You can’t have it all. Sixty years before this became a work/life mantra, it was the core message of Sloan Wilson’s 1955 blockbuster novel, “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit.” Surprised? After a recent reading, so was I. But then, “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” is a book more mentioned than it is read. This could be the most misremembered bestseller of the last century.

The title, which quickly became a catchphrase, seems to describe it all, about a type of executive in post-WWII America who’s exchanged the structure of the military for that of a large corporation. He lives a comfortable but uninspiring life. But if that was all there was, there’d be scant reason for the book’s staggering popularity, or how frequently it’s been cited in sociological studies. It was an immediate bestseller, and the 1956 film boasted an all-star cast that included Gregory Peck, Jennifer Jones and Frederic March.

“The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” was way ahead of its time, and its tenets still apply today: the importance of balancing work and home, of good public schools, and of taking a measured approach to new media (in this case, television). For the 1950s, the novel seems downright subversive: In making his case for a harmonized life, Wilson also exposes the high emotional cost of the traditional American Dream.

Tom Rath, the novel’s protagonist and hero, is an executive and WWII vet who keeps the different aspects of his life (work, family, the war) in apparently manageable compartments. A decade after the war, he still relives brutal memories of combat, and cherished ones of an overseas romance. He may look like other businessmen, but he’s the opposite of a corporate automaton. Tom maintains a wry internal commentary about his social encounters, and lowers his stress level before big meetings by telling himself with a shrug, “It doesn’t matter” — a phrase he used throughout the war, before parachuting from a plane or killing an enemy soldier.

Tom likes his job at a Manhattan-based charitable foundation, but the salary is not enough to lift himself, his wife Betsy and their three young children from their lackluster Connecticut neighborhood into a larger home in a superior school district. Tom and Betsy talk so often about the local elementary school and their kids’ future college prospects, they could be any suburban parents of today, scrutinizing lists like “MCAS Scores Ranked by Town.”

Wilson understood the flashpoints of public education; during the 1950s he served on the National Citizens Commission for Public Schools, and was also the assistant director of the White House Conference on Education. He also wrote other novels, as well as short stories, poems and magazine articles, but he’s chiefly remembered for “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit.”

Tom gets a public relations job at UBC (United Broadcasting Corporation), a behemoth television company founded and run by Ralph Hopkins, whose ability to embrace new technologies has garnered him a vast fortune. For his interview, Tom does indeed don “a freshly cleaned and pressed gray flannel.” He’s amused that his interviewer also wears a gray flannel suit. Tom thinks, sardonically, “The uniform of the day… Somebody must have put out an order.”

If you look at photos of mid-century businessmen, they certainly are a panorama of gray and black and white, even in color photos. However, the deeper into the novel you get, the more those identical suits make you rethink your own work wardrobe. Every era has its corporate uniform, whether it’s a 1980s padded-shoulder power suit or 1990s business-casual khaki.

Set in 1953, the novel is both of its time and timeless. Daily life does seem right out of an early “Mad Men” episode, and at first glance, there seems to be a direct line from this novel to the show that gets all the details right. The Raths have one car and one income. Compared to today’s always-connected parents, Betsy is pretty darn casual about her children’s activities. At UBC, all the managers are men, and all the secretaries are women (who are either efficient or sexy).

These are noteworthy, sometimes cringe-inducing details, but only external ones; the comparisons end there. For example, “Mad Men” may change from year to year, but Don Draper’s work/family priorities never budge: for him, work always wins over family. In contrast, Tom is in a state of near-constant questioning of his true priorities; he often seems closer in character to brooding Michael Steadman, the 1980s-era dad of “thirtysomething.”

Although he has an enviable job, Tom is actually quite cynical about the new technology of television and of UBC in particular, with “its soap operas, commercials and yammering studio audiences.” Years before the 1961 speech in which FCC chairman Newton Minow would call television programming “a vast wasteland,” Tom and Betsy fret about the amount of time their kids spend in front of the TV. But Tom figures the job/money tradeoff is worth it because, as he sees it, you can’t “bring up children in an orderly way without money.”

Career decisions are rarely uncomplicated, and Tom’s reasons for being at UBC are not merely for — in a line often quoted out of context — “a more expensive house and a better brand of gin.” It’s just another plank in Tom’s philosophy of “It doesn’t matter.”

Tom's work time soon stretches late into the evening and even the weekends, and he often works directly with Hopkins. Gradually, he finds himself wondering what it would be like to be so wealthy, to “never to have to worry about frayed shirt collars… to know there's plenty of money to send your kids to college.” But Tom does not want to lean so deeply into his job that he becomes an absentee father like Hopkins.

In a different kind of story, Ralph Hopkins would be a charismatic hero, mythologized like the legends showcased in the History Channel series “The Men Who Built America” — an Andrew Carnegie or J.P. Morgan. Tellingly though, here he’s a cautionary tale. His single-minded ambition has ruined his marriage and alienated his kids.

In a twist that elevates “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit” beyond a period drama, Betsy becomes the one who drives Tom’s journey from closed-off vet to loving husband and father. From the beginning, she offers sound career advice, and stays on point about making a better life for their family. She consistently thinks outside the box, even formulating a bold real estate investment plan, which could improve their lives more than any single job. Betsy embodies the best aspects of Ralph and Tom: fearless about business matters, with an unshakeable loyalty to her husband and kids.

With her as a partner, Tom gains the courage to be honest with himself, with Betsy, and with his boss. Only then can he begin to create his own version of the American Dream. It’s a story revolutionary for the 1950s, and still relevant today.