Advertisement

How A Music Futurist Composes The Future

Dr. Richard Boulanger, a professor of electronic music and design at the Berklee College of Music, lives in a big new house in the woodsy suburb of Dighton. For an avowed futurist, his dwelling is deceptively conventional: plain, spacious, outfitted in soft wall-to-wall carpeting and unremarkable save for the wooden treble clef mounted unobtrusively on the clapboards of the front wall.

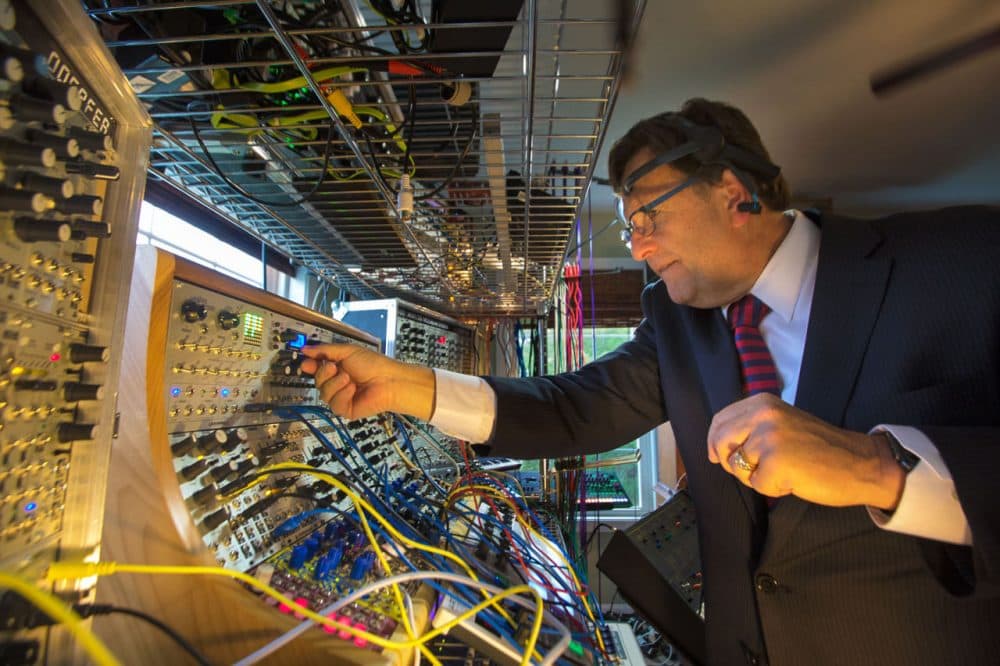

Unremarkable, that is, until you enter Boulanger’s studio on the second floor of the house. In another, less interesting reality, the room would be home to a guest bed or crib, but Boulanger’s babies are of the decidedly non-human variety. They are analog synthesizers, stacked nearly to the ceiling, a riot of knobs and wires and blinking blue lights. Guitars hang next to picture frames, a large keyboard stands in front of a bookshelf, and three computers -- a desktop and two laptops -- dominate the big hardwood desk. This is not the sleek white Apple-store vision of the future, but something altogether Doctor Whovian in its sensibilities, as enamored with the past as with the future’s mind-boggling possibilities.

Boulanger opens up a small closet to reveal stacks upon stacks of classic ‘70s synthesizers. They unleash a cacophony of buzzes and chirps and zaps, “kind of classic, wild, electronic music,” he says. “Soundscapes or sound textures that you might hear in a film or TV show.”

These are the relics of Boulanger’s origins as an electronic music geek. One of the synthesizers, he says, is the very first one that he ever learned to operate, as an eighth grader in 1968. That first brush with the burgeoning world of electronic composition started Boulanger on a path from which he never looked back: an undergraduate degree at the New England Conservatory of Music, followed by a Ph.D in computer music from the University of California, San Diego. Boulanger has been on the faculty at Berklee for the past 30 years.

He composes ambient symphonies peppered with the sounds of nature: ocean waves, croaking frogs, falling rain. He performs his pieces on strange new instruments that he usually had a hand in developing.

Recently, Boulanger composed a concerto for strings and horns with himself as a soloist on a computer program he co-designed, called Muse. The novelty of Muse is that it allows the player to trigger samples -- in Boulanger’s case, those lush natural sounds -- without actually touching a keyboard. Instead, Boulanger waves his hands over a leap motion controller, a small, unobtrusive bit of plastic that picks up his movements and relays them to the computer. When Boulanger plays Muse, he looks like a conductor, fluid and expressive, and not at all like the hunched-over stereotype of a computer musician. And while Muse’s sounds are tailored towards Boulanger’s tastes, the technology contains fascinating possibilities for all manner of electronic music.

Advertisement

“The whole idea is: How will we play music in the future,” says Boulanger. “How will we enjoy making music in the future? With our iPads or our iPhones, or even just the way we move in the room.”

Such a future suggests that musicians will acquire a whole new set of skills. According to Boulanger, “we’re going to have a huge world where the musicians are not only writing songs and producing the songs, but they’re writing the software.”

Standing in his studio in Dighton, Boulanger dons a plastic headpiece resembling something a telemarketer might wear -- The MindWave Mobile EEG Headset, by NeuroSky. It’s a device designed to read “brainwaves,” or the electrical impulses produced by neurons in the brain, and is used primarily as a tool for meditation. Boulanger patches it into a synthesizer, and suddenly the room is filled with the sounds of the activity in his brain: a hectic frenzy of chirps, like a cassette tape on fast-forward. With a bit of work Boulanger is able to tune and tame his brain sounds into a pleasant, if unpredictable, cluster of tones. But the music still has an alien quality to it. Reading our brains is one thing; translating them, another story entirely.

“Just because we can attach sensors to all kinds of data in our world, doesn’t mean that that data will be beautiful music,” Boulanger says. “That beautiful sunset, that beautiful breeze, that beautiful ocean wave, doesn’t necessarily translate into a beautiful melody. It maybe inspires one, but it doesn’t literally map one-to-one.”

The dream, says Boulanger, is that brainwave sensor technology could someday allow a musician to make music simply by imagining it. But if his own experiments tell us anything, it’s that such an instrument is a long ways off, if not entirely out of reach.

Yet Boulanger seems anything but discouraged. On the contrary, his is energized by the musical possibilities contained in technology. The future may not turn out exactly how we imagine it, but it will no doubt be different, dazzling and new.