Advertisement

BSO Gets Its Bard On With 3 Weeks Of Shakespeare-Themed Concerts

William Shakespeare’s legacy transcends literature. From Sergei Prokofiev’s ballet adaptation of “Romeo and Juliet” to Verdi’s opera “Otello” to Duke Ellington’s song cycle “Such Sweet Thunder,” Shakespeare’s work has proven fertile fodder for musical composers of all stripes.

As the 400th year since his death, 2016 is the year of the Shakespeare tribute. The Boston Symphony Orchestra is getting in on the act with three weeks of programs featuring music inspired in one way or another by The Bard.

“Shakespeare is all over the place in everybody’s culture, it seems to me, and I don’t quite know why,” says Harvard University professor Thomas Kelly of the playwright’s influence on music. “There’s something about the human scale of what Shakespeare does that seems to appeal beyond national and linguistic boundaries in a way that a lot of other literary sources don’t.”

The BSO series kicks off on Thursday with a program highlighted by Felix Mendelssohn’s incidental music for “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” (The program will be repeated on Friday, Saturday and next Tuesday, Feb. 2.) The following two weeks will include selections like Shostakovich’s “Hamlet”-inspired suite, Dvořák's "Othello Overture" and Tchaikovsky's “Romeo and Juliet.” The series includes two newer works as well — the world premiere of New York-based composer George Tsontakis’s series of tone poems inspired by Shakespeare’s sonnets (a BSO commission), and Danish composer Hans Abrahamsen’s 2014 piece “let me tell you,” which is based on Paul Griffith’s 2008 novel told from the perspective of Ophelia. (The full schedule can be seen here.)

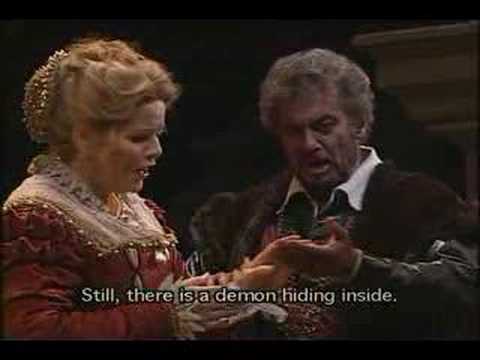

The headline concerts will all be led by conductor Andris Nelsons. Complementary events include chamber music concerts, a semi-staged performance of Verdi’s “Otello” by the Boston Youth Symphony Orchestra and panel discussions moderated by Kelly.

Weston native Bill Barclay, who performed with Actors’ Shakespeare Project in Boston and Shakespeare & Company in Lenox before becoming the director of music for Shakespeare’s Globe in London in 2012, returns to town to direct his adaptation of scenes from “Midsummer” alongside Mendelssohn’s music.

Barclay says his adaptation is framed by Mendelssohn’s efforts to write his piece, for which he expanded upon his very popular overture to “Midsummer,” written 16 years earlier at the tender age of 17.

“What interested me was an adult having to return to the imaginative spontaneity of youth and get back into that freer mindset, that hyper-imaginative mindset, in order to improve upon his incredible work as a 17 year old,” says Barclay, 35.

Barclay’s adaptation focuses on the relationship between Oberon and Titania, the fairy king and queen, and the “Indian boy” over whose custody they bitterly fight. The boy becomes an incarnation of the young Mendelssohn, who entreats his older self to believe again in the magical whimsy of the story.

“How hard is it to slough off the cynicism of adulthood and just believe again in fairies, so to speak, whatever your individual fairies happen to be? What was the imaginary world that you grew up on,” Barclay asks, “and is that world still acceptable to us as we get older?”

This high-concept gloss on the “Midsummer” story is told with four actors — Karen MacDonald, Carson Elrod, Antonio Weissinger and Will Lyman — augmented by soprano Amanda Forsythe and mezzo-soprano Abigail Fischer, doubling as featured vocalists and fairies. The performance also includes video design by Hillary Leben and 45 women from the Tanglewood Festival Chorus.

Barclay, who has composed original music for some Shakespeare productions and directed or acted in others, says the playwright exerts a strong pull on the musical mind, but translation to the musical form is a tricky business.

“The stories are atavistically part of us, but the language has its own needs and desires. It’s a very dangerous exercise because Shakespeare doesn’t need a melody on top of the poetry. The poetry itself, spoken well, is enough,” Barclay says. “Composing for Shakespeare is an exercise in restraint. The poetry is already so complicated that you want the musical gestures to be strong and simple and elegant.”

Barclay notes that Shakespeare wrote his plays to be performed in daylight, with few of the staging elements we now associate with theatrical performance.

“Shakespeare is doing essentially what a composer does, which is to invite us to see something and to own it for ourselves, and not to spoon feed it,” he says. “With Shakespeare you need to imagine it. I think composers see him as a kindred spirit.”

Jeremy D. Goodwin contributes regularly to The Boston Globe, The ARTery (where he is also an editor), Berkshire Magazine and many other publications. See more of his work here. Follow him on Twitter here.