Advertisement

'Female Viagra': Is This The Moral Of The Story Of The Little Pink Pill?

Remember "the little pink pill"? The great brouhaha last year about the FDA's approval of "the female Viagra?"

Let us recap: The drug — flibanserin, brand name "addyi" — is aimed at boosting the libido in pre-menopausal women who have "Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder." (In fact, it's radically different from Viagra, aimed at desire rather than performance and taken daily, not as needed.)

The Food and Drug Administration declined to approve it twice, citing potential harms and marginal benefits. But then, in August — amid head-spinning debate about whether it's sexist to approve a drug for female desire or sexist not to — the FDA said yes. Addyi went onto the market in October.

Now, a new meta-analysis, just out in JAMA Internal Medicine, sums up the handful of existing studies on the drug's benefits — a resounding "eh" — and potential harms.

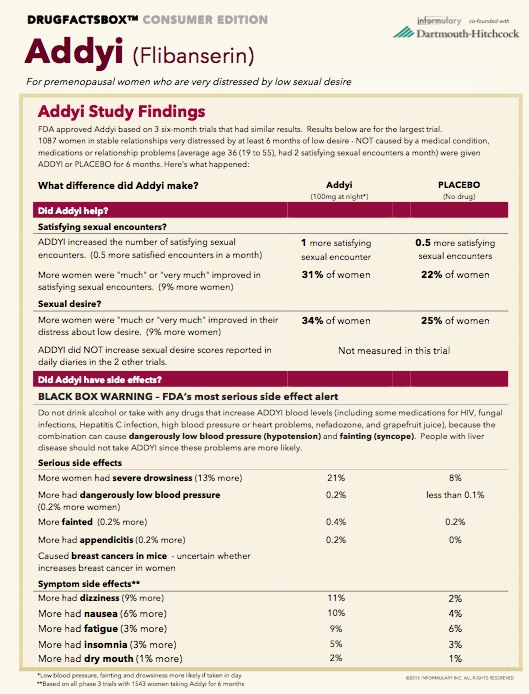

It finds that women who take the daily pill average just one additional "Satisfying Sexual Event" every two months. Compared to placebo, just 10 percent more women who take it report significant improvement in their sex lives.

"I think that what feminism means is getting good drugs that help more than they hurt."

Prof. Lisa M. Schwartz

As for harms, 21 percent of women on the drug reported severe drowsiness, compared to 8 percent on placebo. Of greater concern: When combined with alcohol, the drug can apparently lead to dangerously low blood pressure and even fainting.

The analysis confirms findings from before the FDA approval, and it's not a very sexy picture. That could be why initial sales of Addyi seem to have been lackluster: Bloomberg reports that only a couple of hundred women got prescriptions for Addyi in the weeks after it was released, compared to the half million men who got Viagra in the month after it came onto the market in 1998.

So what's the moral of this story? Drs. Steven Woloshin and Lisa M. Schwartz of the Dartmouth Institute of Health Policy and Clinical Practice wrote a biting editorial to accompany the meta-analysis, sub-headlined "Even The Score Does Not Add Up."

"Even The Score" is the advocacy group that reportedly packed the FDA hearing room with women telling powerful stories of how desperately a treatment for loss of libido is needed. Woloshin and Schwartz write that it "conducted an intense promotional campaign directed at journalists, women's groups, Congress and the FDA."

Advertisement

The campaign, Schwartz says, "ignored the idea about the science and made it all about these charges of sexism, as opposed to the idea that there were real concerns about science here."

"To me, as a woman, I think that what feminism means is getting good drugs that help more than they hurt — or non-drugs. I think it’s important to meet the needs of women, but we want to do that based on good science that tells us that we’re helping more than we're hurting women. Even the Score started to become about something else."

The moral, Woloshin says, is that while under such political pressure, "FDA approved a marginally effective drug for a non-life-threatening condition in the face of substantial and largely unnecessary uncertainty about its dangers."

Unnecessary, that is, because the FDA had told the drug makers what to do to determine the risks — but they didn't do it. For example, Schwartz says, it told the company to test the drug in women who take other medications, but it didn't.

Most strikingly, "The FDA told the company to do a study looking, in pre-menopausal women, how the drug interacted with alcohol and the study was — amazingly — done in men," Schwartz says, "and not just men but men who were moderate drinkers."

That alcohol interaction is the greatest concern about Addyi, and the drug includes a black box warning not to drink while on it. But "I think everyone knows people will drink on this drug," Schwartz says. And if your blood pressure drops to the point that you pass out "and you're driving, you could hurt somebody else. So it has [the potential for] both personal harm plus you could harm somebody else."

The FDA often offers helpful guidance on how to design studies, Woloshin says: "It's really unfortunate that the companies know they don't have to listen."

After years of advocating for clearer public information on the risks and benefits of drugs, Woloshin and Schwartz have started a company to do that: Informulary. Here, with their permission, is their information box on Addyi: