Advertisement

Oral History: Bittersweet Memories Of A Cuban HIV Sanitarium

President Obama's visit to Cuba this week has highlighted the fading of U.S.-Cuba alienation — but also the deep and lingering differences between the two countries, on issues from freedom of speech to free health care.

Here, reporter Rebecca Sananes shares a chapter of medical history in which Cuba chose a policy diametrically opposite to America's: Back in the 1990s, Cuba created a network of sanitariums, where people with HIV were confined indefinitely. It sounds barbaric, but as former patient Eduardo Martinez's recollections reveal, it's complicated. Life in the sanitariums was so much better than outside that some people purposely infected themselves with HIV.

By Rebecca Sananes

Guest contributor

On a terrace outside his Havana apartment, Eduardo Martinez nurtures a small tree. On a recent sun-drenched tropical afternoon, he looks up at its streaked, shade-giving leaves fondly.

“I got it when I was in the sanitarium. I put it in my living room and it began to grow until it reached the ceiling,” he recalls in Spanish through a translator.

When he left the sanatorium in 1996, he took a clipping from the plant. “It was so small," he remembers. "But it has turned into this forest that you have here -- so this is a memento from that time.”

It was a complicated time — the early years of AIDS in Cuba, after the virus arrived on the island in 1986. The Cuban government created a system of 14 sanitariums around Cuba, where anybody who tested positive for HIV was sent for life. Eduardo became one of them in 1991, and is one of the only people of his sanitarium generation still surviving.

Today, his Havana apartment is adorned in paintings and awards accrued over a lifetime.

The sanitarium system was controversial. Critics called them prisons; supporters credited them with damping down the epidemic. Eduardo calls the sanitariums a double-edged sword.

“The purpose of the sanitarium was to stop the disease from being spread," he says, “which was unsuccessful, because the disease continued to propagate.”

Only one sanitarium remains -- the first one to open, the one Eduardo called home for five years in Santiago de Las Vegas outside of Havana. Now, the sanitarium is more hospital than quarantine, a voluntary clinic for those who need extensive HIV care.

Eduardo has lived with HIV for 25 years. “As compared to before, HIV today is like a cold,” he says.

Today, Eduardo puts on extravagant fashion shows and performances at the Tropicana -- one of Havana’s most famous nightclubs — for audiences including the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Cuba.

When he’s on stage, he transforms himself into a towering blond woman named Samantha. But back in 1991, Eduardo thought he was at the end of his career — and possibly his life.

He had been a well-known designer, creating costumes for popular television shows and calling himself the ‘Christian Dior of Cuba.' At the height of his career, on one of his costume tours, he had an affair with a dancer.

“He didn’t know that he had HIV,” Eduardo recalls. “And when the tour was finished, I came back to Havana and some months thereafter, I began to feel bad.”

A doctor-friend sent him for an AIDS test, which came back positive. But unlike many Cubans at the time, Eduardo had what he remembers as a good life: a booming career, and a family. For him, being sent to the sanitarium would mean this lifestyle was over. For a full year, he kept the diagnosis secret, as the doctor waited for room in a sanitarium. Finally, one day came a knock on his door.

“I didn’t want to go, but they would come for you and take you by force,” he recalls.

This unwillingness to go to the sanatoriums was not the case for all Cubans. In fact, some were actively infecting themselves with the virus because the facilities of the sanatorium were rumored to be beautiful and safe for the gay population.

Joel Perez, Eduardo’s longtime partner, who is also HIV-positive and spent time living in the sanitariums, remembers that though security guards protected the grounds, “many people went to the perimeters of the sanitarium to get infected with syringes. People always managed to get around and get inside the sanatorium in order to get the virus.”

"I couldn't just lie down there and wait for death."

In the sanitarium, Eduardo did have the rare luxury of living in one of the few places in the country that had air conditioning, livable apartments and reliable food. But he fell into a depression and spent a month living in a psychiatric ward.

"At first, it was very sad for me, because I didn't understand why I was infected and why I had to go be interned in that place," he says. "And on top of this, that was killing my career. I was at the top of stardom at that moment. I went on a hunger strike when I arrived."

Soon, however, he reconciled himself to the idea that the sanitarium was his whole world for the foreseeable future. “I couldn’t just lie down there and wait for death," he recalls. "I was an active professional. And I waged a revolution there.”

So, tucked away from the rest of the world, "Samantha" was born.

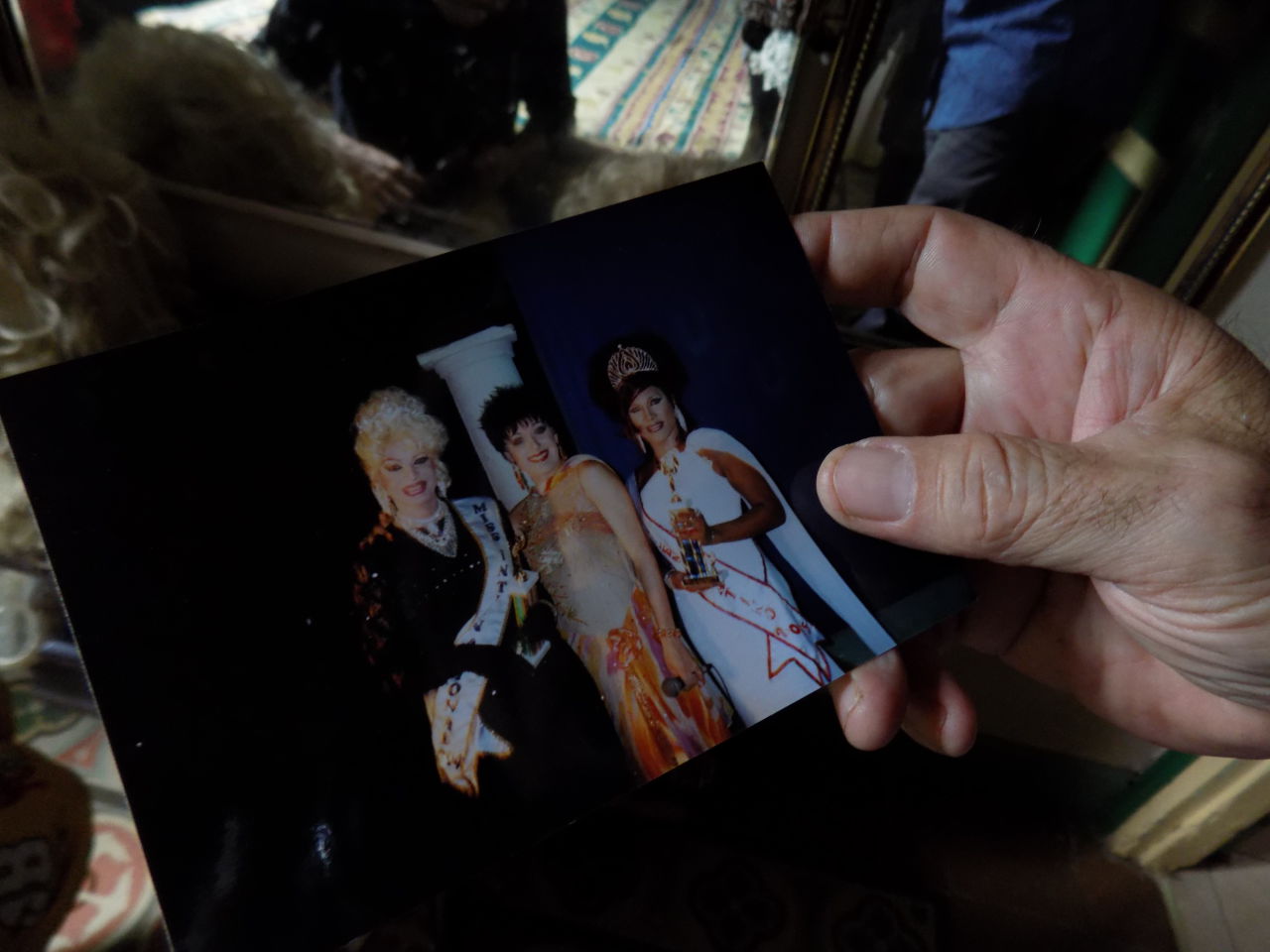

“That was where I transformed myself for the first time” he reflects in his current Havana apartment filled with tiaras, blond wigs and trophies. “I needed a model in order to continue producing designs, and I just used myself as a model."

But Eduardo did not just transform himself. He took his fellow patients — including the cover-art designer of then-President Fidel Castro’s books — and built a community of artists devoted to self-expression.

Eduardo began to change his attitude about the sanitarium: It was no longer his prison, but what he called his "big house."

“I used everybody around me, I made fashion shows, I made a movie theater, I created theater, so I revolved everybody around me,” he says.

In many ways, he became a resident therapist, he says: “The patients were needing a lot of entertainment, distraction.”

He was even provided a budget and facilities from the sanitarium in order to put on his shows. “I came to discover that if I kept the mind of the patients busy, the immune system wouldn’t be depressed,” he recalls.

And while the gay community outside the sanitarium struggled against violence and discrimination, the sanitarium became a place of refuge. Eduardo praises the sanitarium doctors at the time as open-minded: “If they didn’t have an open mind, they would have to, because there were many gay people there,” he says.

Like the rest of the world, Cuba sought cures for HIV, and many patients in the sanitariums became the test subjects for potential cures. Eduardo was slated to be one of them before he opted out of a controversial experiment.

"The people who participated in it, all of them died."

“It consisted of heating the blood in order to see if [...] with the reheating of the blood, if the virus would die” he explains. “But the thing is that with this, not only would the virus die, but also the proteins would be put down.” The night before he was slated to go through with the test, he decided against it — a decision he now sees as a narrow escape: “The people who participated in it, all of them died.”

By 1995, the government could no longer afford to house HIV patients for life. Some patients left of their own volition and eventually the remaining patients were kicked out. Eduardo was one of the first patients to be offered his freedom, but just as it was difficult to go into quarantined life, it was hard to come out: “I refused to leave because I said I was too committed to the community inside the sanitarium,” he says.

But by 1996, he knew it was time to go. In spite of the homophobia and discrimination against those who were HIV-positive that persisted in Cuba, Eduardo persevered, and built what he now calls his second career — for which he partly credits the sanitarium: "That's where Samantha started," he says with a proud smile. “I was the first one who engaged in doing very daring things. Never before had there been cross-gender performers at Tropicana.”

When Eduardo thinks of the sanitarium these days, he cries. “What makes me sad is that those friends of mine that I had at those moments couldn’t reach this moment of happiness,” he says. The memories are poignant, bittersweet: “At that time, we would always dream if we had a theater to do our trans-shows," he says. "We never thought it would be possible.”

And despite his hardships, he smiles. “I’m happy to have been able to reach this moment.”

Rebecca Sananes interviewed Eduardo Martinez while in Cuba recently on a student fellowship through the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.